Kaye Don was a man of many achievements, from powerboat and car record breaker and racer, to sporting motorcyclist and manufacturer. He was also the first to put an electric start British motorcycle into production.

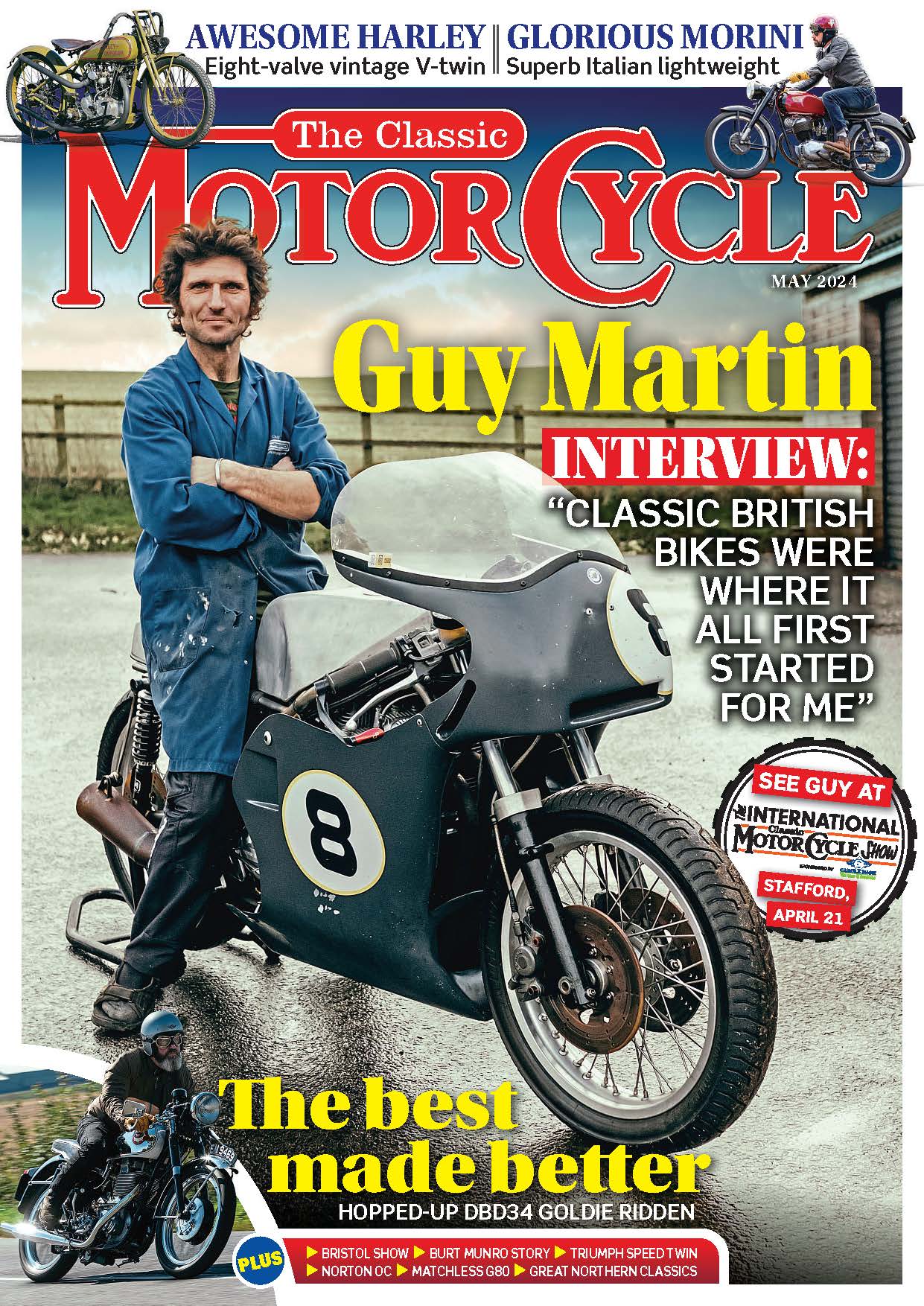

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Words: ALAN CATHCART Photographs: KEL EDGE

Compared to war-ravaged Italy, France and Germany, bombed-out Britain didn’t experience the same post-Second World War boom in new motorcycle registrations, despite a similar chronic lack of personal transportation. That’s because the UK Government prioritised earning precious foreign currency – principally, US dollars – over the convenience of its population, by exporting the products of the various local motorcycle manufacturers in return for granting them access to postwar stocks of scarce materials like steel, aluminium and rubber. So new motorcycles for British customers were hard to obtain, and much prized.

It was a situation ripe for the entrepreneurial talents of a well-connected person like Kaye Don, who founded the Ambassador Motorcycle Company in Ascot, Berkshire in 1946, to provide a range of basic transportation models powered by the 197cc Villiers 5E two-stroke motor, with a bolted-on three-speed gearbox. Don was a man whose life story is strictly Hollywood, though no movie script could do justice to the breadth of achievement this undoubtedly brave and determined individual managed to accomplish during his 90 years on earth, ending on August 29, 1981.

Born Karl Ernest Donsky in 1891 to Polish parents living in Dublin – then a part of the UK, hence he was British – he adopted the sobriquet of Kaye Don in joining the Avon Rubber Company in Melksham, Wiltshire, at the age of 17. Already an avid motorcyclist since the early days of such devices, he rode bikes like Zeniths and a Diamond to numerous records at Brooklands, in between working his way up the Avon management ladder to become sales director of the company by the time he left them in 1928. This was despite taking temporary leave with the advent of the First World War to join the Royal Flying Corps as a pilot, serving as a reconnaissance observer for the Royal Artillery in an RE8 over the Western Front. Having seen through what was an extremely risky wartime occupation with a low survival rate, Kaye Don rejoined Avon after the Armistice, and resumed racing bikes successfully at Brooklands before progressing to cars, taking over 100 speed records there between 1919 and 1930 on a wide variety of vehicles. As his full-time chief race engineer for all his competition activities up until 1934, he employed a man named Charles Cooper who later founded the Cooper Car Company in 1946 together with his son, John. The products of their Surbiton factory close to Kaye Don’s home in Kingston-on-Thames dominated the Formula 3 racing car category from 1948-60 with 500cc motorcycle engines positioned behind the driver, which in turn led to the mid-engined Cooper-Climax driven by Aussie Jack Brabham to win two Formula 1 World Championships in 1959-60.

In 1924, Kaye Don acquired the aero-engined Wolseley Viper V8 as his personal Brooklands device, powered by an 11.7-litre V8 Hispano-Suiza OHC motor built by Wolseley Motors under licence during the First World War. Based on his success with this car in 1925, Don became a works driver for the Anglo-French Sunbeam car company driving three different cars, each fast and very well engineered, which he christened the Cub, the Tiger and the Tigress. The Cub was powered by a supercharged straight-six 1988cc engine producing 145hp, and with it Kaye Don won the Gold Vase at Brooklands in 1927, and would later lap the Outer Circuit at over 126mph in the car. But as a mark of Don’s versatility in 1926 he also set a new 500cc 10-mile record at 65mph aboard the wooden-framed Jappic cyclecar, powered by a 495cc JAP single-cylinder OHV motor!

However, it was in the works-prepared 3976cc supercharged V12 Sunbeam Tiger, which had been built to secure the World Land Speed Record, as it did at 152.33mph on Southport Sands in 1926 in the hands of Sir Henry Seagrave, that Kaye Don became the first person to lap the bumpy, steeply banked Outer Circuit at over 130mph, setting a new absolute record of 131.76mph in September 1928 – Seagrave had retired from racing in 1924 to focus uniquely on breaking records. That same year Don was awarded the first ever BRDC Gold Plaque both for his Brooklands record and for winning his own first-ever road race, the inaugural Tourist Trophy held on the Ards Circuit in Northern Ireland, by seven seconds, in his Meadows-engined Lea-Francis Hyper TT model. Also in 1928, he became British Motor Racing Champion for the first time, repeating the achievement in 1929 after raising his Brooklands lap record to 134.24 mph. Indeed, he was the only driver to lap Brooklands at over 130mph during the 1920s.

In 1930 Charles Cooper travelled to the Bugatti factory at Molsheim to help assemble the 4.9-litre straight-eight Type 54 on which Kaye Don achieved so much success at Brooklands in following years, although it was in the V12 Sunbeam Tigress, a sister car to the Tiger that in June that year he raised his own Brooklands lap record to 137.58 mph. And in March that same year he’d attempted to break the World Land Speed Record at Daytona Beach aboard the Sunbeam Silver Bullet powered by two supercharged V12 aircraft engines of 24 litres each, a monstrous car with an extremely advanced design including an adjustable rear aerofoil to generate downforce, and reduce wheelspin. But it was however sadly underdeveloped, so that the attempt failed, thanks also to less than ideal weather conditions.

However, Kaye Don had better luck on water than on land, in 1931 and 1932 three times breaking the World Water Speed Record in Miss England III as part of his fierce rivalry with American Gar Wood, leaving it at 119.81mph in July 1932 recorded before 20,000 spectators on Loch Lomond. This came after he’d taken over the rebuilt boat powered by twin Rolls-Royce V12 engines in which Sir Henry Seagrave had been killed attempting the same feat on Lake Windermere.

Continuing to race cars successfully in a variety of vehicles, Kaye Don was entered for the Mannin Beg sports car race in the Isle of Man in May 1934, driving a works supercharged MG Magnette, but suffered brake and steering problems in practice which factory mechanic Frank Tayler endeavoured to fix. An open roads test after dark with both men aboard saw the car collide with another vehicle and Tayler thrown out and killed, while Don was badly injured. During his year-long recovery he was prosecuted for manslaughter in July that year and convicted by a majority jury verdict of seven to four, serving four months in Jurby prison before competing in one final car race in the 1936 Donington GP, sharing a 3.6-litre Delahaye with its French owner, René le Bègue, and then retiring from racing thereafter. The jail term most likely explains why, despite being arguably the greatest all-rounder in extreme motor sports during the prewar era, Don was not accorded the same knighthood bestowed on other record-breakers like Malcolm Campbell, Henry Seagrave and Tim Birkin.

During the Second World War, Kaye Don became a supplier of various items of key merchandise to the War Office, which most likely explains his ability to conjure up sufficient supplies of scarce materials so soon after the end of hostilities to produce enough Ambassador motorcycles powered by the Villiers 8E 197cc single-cylinder two-stroke motor to make establishing a company to do so viable.

Employing up to 250 people at his engineering works at Ascot, and another at Bracknell, where he was the official UK importer for Pontiac cars from America and, later on, Zündapp motorcycles and scooters from Germany, the three-model range of Ambassador bikes whose styling he designed himself (as he had his series of racing boats) expanded to meet demand. The first very basic rigid Popular model with a girder fork was sold without the lighting set provided on the otherwise identical Courier, while the top-priced Embassy model had Ambassador’s own telescopic fork and plunger rear suspension. The range-topping Supreme was added above this in 1951, still using a plunger frame, with a second Supreme variant named the SS (as in, Self Starter), which was equipped with an optional Lucas electric starter driving a belt to turn the crankshaft. But few of these were sold as customers apparently didn’t consider that push-button starting was worth the extra cost.

In 1953 the Ambassador range was revamped, with the Supreme now using the new 225cc Villiers 1H single-cylinder engine – one of which produced onSeptember 26, 1956 was Villiers’ two-millionth engine made since it was founded in 1898 – fitted in a frame featuring swinging-arm rear suspension for the first time on one of the company’s models. But it was the introduction of the first Villiers parallel-twin motor, the 249cc 2T in 1956 which finally permitted Kaye Don to head truly upmarket with Ambassador models.

Being better finished and more substantial than their fellow-Villiers powered rivals like Sun, James, Excelsior, Panther, Cotton, Norman, Greeves etc. etc., his bikes had struggled on price to appeal to owners seeking basic transportation. Measuring 50×63.5mm with a 180° crankshaft (so, one piston up, one down), the 2T was essentially a pair of 122cc Villiers single-cylinder motors with a slightly longer stroke mounted on a common crankcase. Each cylinder had its own crankshaft separated by a disc in the crankcase holding a central bearing, with a roller bearing on the magneto side and ball bearing on the drive side, and the small ends of the steel conrods consisting of steel-backed brass bushes.

The cast iron cylinders carried aluminium heads, and the 15bhp at 5500rpm was sufficient to propel the Ambassador Super S carrying this motor to a top speed of 70mph. Kaye Don’s bodywork styling with an enclosed rear ‘bathtub’ section included a plush, comfortable seat, a large (for a 250cc lightweight) seven-inch Miller headlamp, and deeply valanced mudguards perhaps inspired by the Indian Chief. Indeed, the Ambassador range was extended to include a foray into the US market, via the restyled America Supreme model, replete with a gaudy chromed tank.

In August 1960, Ambassador unveiled its most luxurious and ultimately range-topping model, the four-speed Electra 75, which claimed to be the only British motorcycle with an electric starter included as standard. Unlike the previous rather crude Supreme SS with its belt-driven electric leg, this featured an enclosed gear-driven 90-watt Siba Dynastart starter-cum-generator neatly mounted on the right side of the motor, behind a cover bearing a slot for the ignition key to be inserted, which the rider then turned to fire up the engine. The system added a meaty 28lb/12.7kg to a bike which now weighed 318lb/147kg dry, though the Villiers motor was pepped up a little by raising the primary compression ratio to 10:1 (vs. 8.2:1 on the Super S) with a 2mm larger 25mm Villiers carburettor, all sufficient to boost top speed to 75mph, hence the name tag.

Though undeniably pricey at £217.2.6 including 21% purchase tax compared to £196.12.5 for the slightly less potent Ambassador Super S – itself a luxury model versus the similarly engined James Superswift at £181.18.8 – the Electra 75 sold sufficiently well to justify its development. But in 1962, not long after his 70th birthday, Kaye Don decided to retire and devote his time to his other passion, gardening. He therefore arranged to sell Ambassador to fellow manufacturer DMW (standing for Dawson’s Motor Works) in Wolverhampton, whose founder Leslie ‘Smokey’ Dawson, a speedway and grasstrack star of the 1920s and 30s, had been the first manufacturer in Britain to offer telescopic fork and swinging arm rear suspension conversion kits from 1943 onwards under the Telematic label. He sold out to local businessman Harold Nock, who added brakes and wheel hubs to the range, marketed under the Metal Profiles label, before commencing manufacture of complete DMW motorcycles powered by Villiers engines built just a couple of miles away, in 1950. Kaye Don continued advising Nock as a consultant for three more years until 1965, when he finally retired, and Nock decided to fold Ambassador into DMW, so the marque ceased to exist.

Ambassador motorcycles are a comparative rarity today, and the range-topping Electra 75 all the more so – hence the inevitability that one should be found in perfect running order in that repository of such devices, the Sammy Miller Museum () on England’s South Coast. “I was looking at a collection in the Lake District in Spring 2021 with this bike in it, and I took a real shine to it,” says Sammy. “The styling is very futuristic for its time, and it’s one of the first electric-start bikes to be offered for sale anywhere in the world. Plus, it came in very good condition – all we’ve given it in the workshop is a big tidy-up. See if you don’t agree that this is a hidden jewel of the Swinging Sixties!”

Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder, but I do personally think that the SMM’s Ambassador Electra 75, in its Royal Gold and Raven Black livery, is a standout looker by early 1960s standards. If he did indeed style it himself, as was apparently the case, then Kaye Don had another string to his bow besides being able to control monstrous-engined motor cars and power boats at very high speed. The bike’s lines are clean, curvaceous and luxurious-looking, quite out of keeping with the expectations aroused by its humble Villiers twin-cylinder ancestry – and it’s also quite unexpectedly plush to ride. The spacious seat with plenty of room for a passenger is improbably comfy to straddle by 1960s standards, and the riding stance is very relaxed, with the slightly pulled-back but relatively high handlebar grips in best fall-to-hands cliché mode.

It feels a bigger bike than a 250cc twin, though I’m not sure about the aesthetic merits of the flat expanse of painted metal clipped to the handlebar to conceal it from view, with just a single red ignition light in its centre.

Make sure the clean-shifting one-up right-foot gear lever with a marker gate on the right engine cover just behind the ignition key’s slot is in neutral, bend down to put said key into the slot and twist to the left, and the Electra 75 whirrs instantly into action – though you need to have your left hand on the throttle to catch it as it does so from cold. Warm is okay – it just starts and idles. The 180° crank motor is both smooth and relatively silent, with little vibration apparent anywhere, either in bodily contact points (seat, handlebar ends, footrests) or in rpm. Rev it, and apart from clouds of blue smoke emanating from the long twin exhausts which soon clear, there are no intrusive vibes. I’d say whoever rebuilt this engine before the bike came into Sammy’s hands knew what they were doing. It’s really nice to ride, and surprisingly torquey for a 250cc two-stroke twin.

Bottom gear is really low, as if it were made for sidecar use, but the engine is so flexible I could even take off from rest in third gear without slipping the clutch much. But once under way the Ambassador purrs along at 65mph in completely unstressed manner, and pretty silently, too. It’s a bike which lives up to its appearance – by its looks you expect it to be smooth and classy to ride, and it is. I was honestly surprised at how much I enjoyed riding it – I hadn’t expected it to be anything like as relaxing and easy to settle into as it was.

The ride quality was pretty good, too, with the relatively skinny Metal Profiles fork damping out the worst of the road rash on the New Forest roads around the Sammy Miller Museum. The Taiwanese Cheng Shin 17-inch tyres Sammy has fitted to the bike may not be the whitewall rubber the Ambassador originally came fitted with, but they seemed to grip okay when I got a little enthusiastic in corners when returning the Electra 75 to home base.

Watch out for the seven-inch Albion SLS drum brakes, though – the front one was amazingly fierce by the standards of the day, and I certainly wouldn’t like to ride this Ambassador in the rain until I’d slackened it off a fair bit. The rear one was better, but it seemed to pay off to keep them both warm by fingering/footing the brake levers while running in a straight line. I suspect a change of brake linings on the Ambassador would be a good idea, to resolve this.

But, that apart, this was a quite unexpectedly enjoyable afternoon ride through the New Forest lanes – complete with the added convenience of an electric start system that actually worked well. In addition to his breath-taking bravery on four wheels (and two) and on water, Kaye Don evidently knew a good bit about motorcycle design, too.

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.