Nobody could ever accuse the early-vintage Triumph of being anything, other than trusty- and 30,000-odd dispatch riders of World War One would swear to that. Yet it must be said that the Coventry firm were not exactly in the forefront of technical development. They had never built a sporty overhead-valve model of any kind, they still stuck to that peculiar fore-and-aft front fork that afforded a varying wheelbase as one rode the ripples, and not until 1915 (with the coming of the 550cc Model H) did they abandon the three-speed rear hub in favour of a countershaft gearbox.

Even at that, the Model H's gearbox was a proprietary Sturmey-Archer, with vee belt final drive. So when the rumours began to fly around, that Triumph were entering a team of bikes for the 1921 Senior TT, a few eyebrows were raised. Naturally enough, the Model H had continued into post-war production, partnered by an all-chain-drive Model SD which featured Triumph's own design of gearbox, with primary drive on the left and final drive on the right. These, though, were both 550cc side-valves. Clearly, Triumph were working on a new five-hundred.

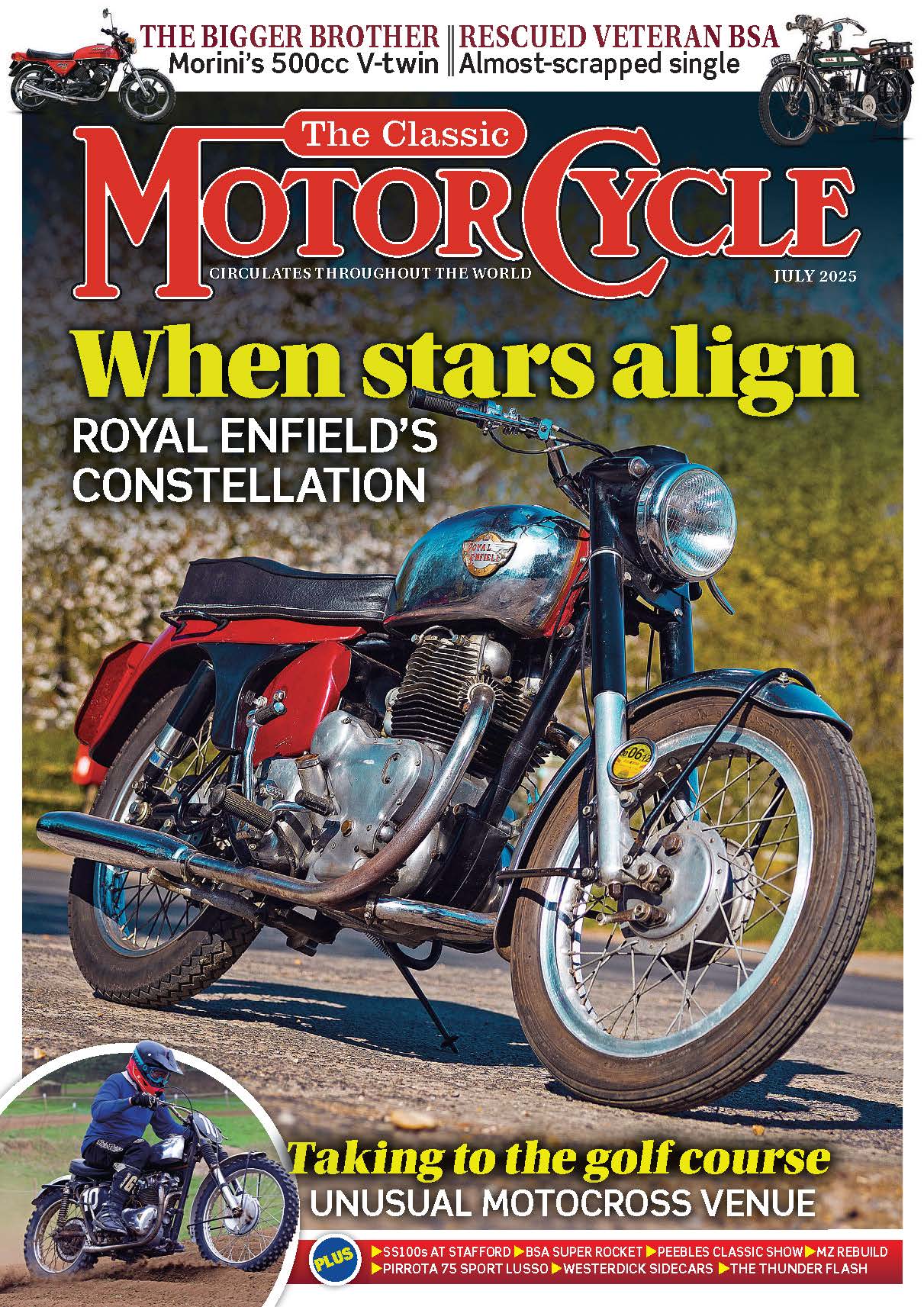

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Or to be accurate, Ricardo and Co Ltd were working on a race engine on behalf of Triumph, though Coventry were holding a tight grip on the purse-strings. Harry Ricardo, even by 1921, had achieved an enviable reputation for his researches into what we would today call 'gas-flowing', and for Triumph he now produced a four-valve ohv engine, having a cylinder barrel machined from a steel billet. The machined steel cylinder (in 45 per cent carbon steel, by the way) was, said Harry Ricardo, to avoid warping through an uneven wall thickness.

Oddly enough, the cylinder head was of cast-iron, and was secured by five long studs which engaged not with the crankcase mouth but with the lowest of the cylinder-wall fins; below that, there was an expanse of perhaps of plain, unfinned barrel.

Oddly enough, the cylinder head was of cast-iron, and was secured by five long studs which engaged not with the crankcase mouth but with the lowest of the cylinder-wall fins; below that, there was an expanse of perhaps of plain, unfinned barrel.

Rather enterprisingly – for aluminium was still regarded as 'trouble metal' in 1921 – the slipper piston was in light-alloy, liberally drilled, and weighing only 14oz complete with piston rings and gudgeon pin.

The four valves were not arranged radially, but were two-by-two in pentroof style, operated by ball-bearing rockers carried in pillars cast integrally with the cylinder head. In the fashion of the time, of course, the valve gear was totally exposed and unlubricated. For the first time on any motor cycle engine, Ricardo employed his patented 'masked inlet valves', the heads being sunk below the level of the combustion chamber so that the first part of the opening, and the last part of the closing are practically ineffective; cam design was such that the valves were gently started and gently seated, the theory being that the effective valve opening and closure was sudden in each case. Whatever the notion, it certainly made for very quiet operation.

Lower-half assembly – which was not Ricardo's province-was essentially that of the Model SD cooking job and, also, Model SD cycle parts were employed including Overhead valve arrangement showing the ball bearing rocker arms and double exhaust pipe.

(initially, at any rate) the famous Triumph rocking front fork. However, in view of the increased power, dummy vee-rim brakes were fitted at front and rear.

Preliminary testing at Brooklands was undertaken by Major Frank Halford (later a renowned aero-engine designer) on behalf of the Ricardo company, and George Shemans, for Triumphs. The tests embraced over 100 laps of Brooklands at lap speeds between 65 and 79mph, while on the bench a figure of 20bhp at 4,600rpm was obtained. Encouraged, Triumphs entered a three-man team for the 1921

Senior, comprising George Shemans, Stanley Gill, and Charles Sgonina – but to be on the safe side, they entered, also, six new 500cc side-valve models.

When the bikes got to the Island, the riders found that the Triumph forks were unsuited to high speeds, and there was a wholesale and hasty switchover to side-spring Druid forks, for both the Ricardo and the side-valve models. And perhaps it was just as well that the works had hedged their bets, because the Riccys were too new to give of their best under pressure and only Shemans (in 16th place) was a finisher.

Nevertheless, the Ricardo went into production for the 1922 season, though development had continued apace and quite a number of changes had been made. Mainly, the steel cylinder had been replaced by a cast-iron component, and the rocking front fork had given way to a Druid pattern, made under licence at the Triumph factory. To retrieve something of the Ricardo reputation and to send the production model on its way with a fanfare of trumpets, Frank Halford indulged in a record-smashing session at Brooklands just before Olympia opened its doors. So the factory could now point with pride to a flying mile record at 83.91 mph, and a new one-hour record at 76.74mph, plus a 50-mile figure of 77.27mph. All stirring stuff.

Nevertheless, the Ricardo went into production for the 1922 season, though development had continued apace and quite a number of changes had been made. Mainly, the steel cylinder had been replaced by a cast-iron component, and the rocking front fork had given way to a Druid pattern, made under licence at the Triumph factory. To retrieve something of the Ricardo reputation and to send the production model on its way with a fanfare of trumpets, Frank Halford indulged in a record-smashing session at Brooklands just before Olympia opened its doors. So the factory could now point with pride to a flying mile record at 83.91 mph, and a new one-hour record at 76.74mph, plus a 50-mile figure of 77.27mph. All stirring stuff.

When the 1922 Senior TT models were announced, it was very evident that a considerable degree of redesigning had been undertaken during the winter, for now the dimensions were almost square at 85 x 88mm, the exhaust ports were much more widely splayed, and the valve area was reputedly 25 per cent greater than before. The central sparking plug position was retained, but now an alternative side-mounted position was available. Smaller but wider cams were fitted in the timing gear, and there was dry-sump lubrication, served by a twin plunger oil pump.

The vee-rim rear brake was retained (The Motor Cycle called it 'excellent') but a new contracting-band front brake had been fitted. Previously with the Rover squad, a young Coventry rider named Walter Brandish had been recruited into the Triumph team, and the factory's faith in him was certainly not displaced for he was to finish second to Sunbeam man Alec Bennett – that in spite of losing second gear from his close-ratio three-speed gearbox from the third lap onward.

It seemed, however, that the Riccy was fated never to achieve the greater glory, for although Triumph could point to a whole trunk-load of continental successes, and to gold medals in the ISDT and the LiegeParis-Liege marathon, a Senior TT victory-which would have made all the difference – never came its way.

The big year should have been 1923, when Walter Brandish was being widely tipped as the likely winner. Backing him up on Ricardos were Geoff Davison (the 1922 Lightweight TT winner), and R.J. Braid, and early practice periods showed 22-year-old Brandish to be much the quickest.

But the Saturday morning practice brought dismay. Hurtling down from Cregny-Baa towards Hillberry, Brandish tried to overtake a Sunbeam rider, the Triumph got its wheels into the gutter, and he was thrown, breaking his right leg below the knee. Coming along behind, Geoff Davison stopped, grabbed the red blouse of a woman spectator, and used it as an impromptu warning flag to other riders.

But the Saturday morning practice brought dismay. Hurtling down from Cregny-Baa towards Hillberry, Brandish tried to overtake a Sunbeam rider, the Triumph got its wheels into the gutter, and he was thrown, breaking his right leg below the knee. Coming along behind, Geoff Davison stopped, grabbed the red blouse of a woman spectator, and used it as an impromptu warning flag to other riders.

Up to that point, the left-hander on which the accident took place had had no particular name. But we know it now as Brandish Corner.

But in any case, the performance of the Ricardo four-valver was beginning to be eclipsed by a rather simpler two-valve engine, developed at Brooklands by Vic Horsman. Triumph bought the design of the Horsman engine, which thereafter became the Triumph Model TT, and gradually shouldered the Model R out of the range. The Riccy didn't survive to become a saddle-tank model, and 1927 was the last year it was included in the catalogue. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.