“We should have thrown the whole motorcycle and engine away, and started again,” sighs Mick Broom, as he recalls post-production problems that tarnished the Hesketh V1000’s image as ‘the finest motorcycle in the world’. “It definitely needed more money and development time. I was an engineer, but suddenly I found myself involved in all sorts of political decisions, having already sent a memo which stated that the bikes weren’t good enough for the press to ride.”

As the first motorcyclist to join the team of hot young racing car designers that had dreamed up the Hesketh motorcycle concept, 34-year-old Mick’s pragmatic approach to engineering contrasted with the established Formula 1 methodology of sticking to exact specifications for bought-in components. Although the V-twin’s essential dimensions were already drawn, he worked extensively on each of the four prototypes and so found himself back in familiar development territory, when serious production faults forced Hesketh Motorcycles into receivership during the summer of 1982.

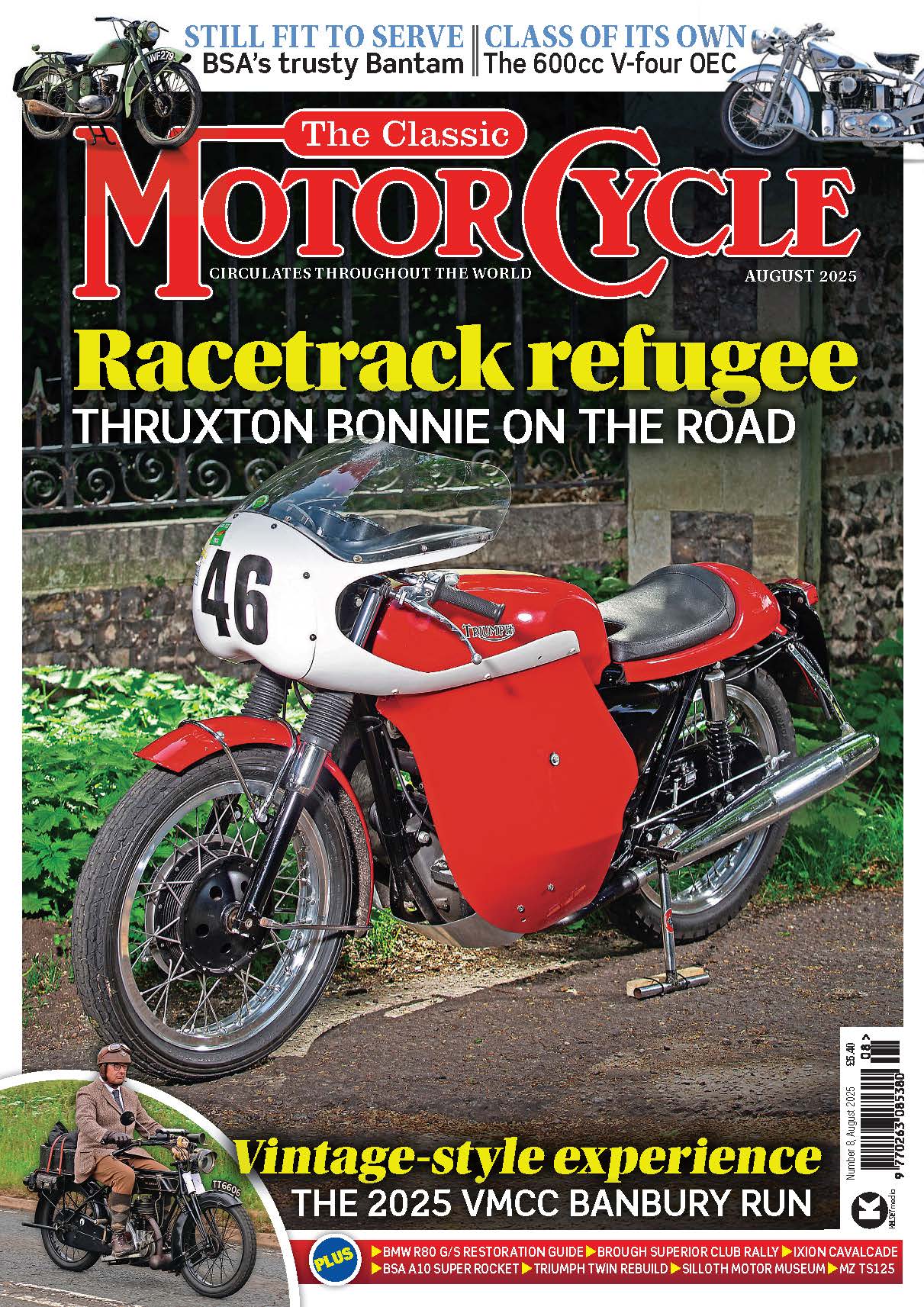

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

“The transmission had a fundamental design flaw,” explains Mick. “The cast iron flywheel was too light, meaning that the crank would speed up for each power pulse and then slow as it lost energy. This resulted in the gearbox shafts rotating out of synch, slowing down engagement, while the whole lot would clatter at low revs, especially in a high gear. Under pressure to deliver a quick fix, we cut a step in each gear dog to take up free play, although this two-stage process required a slow lever action and sometimes made it tricky to select the next ratio.

“The transmission had a fundamental design flaw,” explains Mick. “The cast iron flywheel was too light, meaning that the crank would speed up for each power pulse and then slow as it lost energy. This resulted in the gearbox shafts rotating out of synch, slowing down engagement, while the whole lot would clatter at low revs, especially in a high gear. Under pressure to deliver a quick fix, we cut a step in each gear dog to take up free play, although this two-stage process required a slow lever action and sometimes made it tricky to select the next ratio.

“All the development money was being diverted to the factory at Daventry from June onwards, so I quietly got my lads working on a few long-term engineering solutions in the stable block at Easton Neston. One problem that we knew about was resistance to oil flow in the feed pipes and cooler, which ran at higher pressure than the blow-off valve. It meant that that oil pressure could reach about 250lb when cold and when hot could suddenly drop to zero. A bigger oil pump was impractical, so we devised a double-stage pressure system and a new shape for the oil reservoir. Almost by accident, we noticed that both pistons were facing the wrong way, because nobody had told the production engineers that the crank rotated backwards, just as nobody had told the bearing people how hot the engine cases could get. I called all this ‘under the bench’ work EN10, which stood for Easton Neston Mark 1.0, and it quickly became a rolling package as bikes came back to us for improvements, sometimes several times before they were right.”

Derek Sturgess, 46, from Kettering, owns a unique example of a Daventry-produced bike that got the EN10 treatment during this time. “From what I've heard, a wealthy patriotic customer ordered a red bike plus a blue one and this one,” says Derek of his unique machine, which was supplied by a Suffolk dealer. “The Old English shade of paint is creamier than pure white and has a gold-painted signature on the fuel tank and fairing.” Like Lord Hesketh, Derek is well over six feet tall and doesn’t find his 1982 V1000’s seat height an issue. In fact, he'as lowered its footrests for extra comfort.

Derek Sturgess, 46, from Kettering, owns a unique example of a Daventry-produced bike that got the EN10 treatment during this time. “From what I've heard, a wealthy patriotic customer ordered a red bike plus a blue one and this one,” says Derek of his unique machine, which was supplied by a Suffolk dealer. “The Old English shade of paint is creamier than pure white and has a gold-painted signature on the fuel tank and fairing.” Like Lord Hesketh, Derek is well over six feet tall and doesn’t find his 1982 V1000’s seat height an issue. In fact, he'as lowered its footrests for extra comfort.

Mick continues the Hesketh story: “Eventually, of course, we were all sacked. The receiver owned all the company’s assets, but not our skills and knowledge, so I suggested that we stay together as a unit. I bought a gearbox jig from the dispersal auction, but afterwards we tracked down whatever spares and tools we could rescue from the scrapheap.” Lord Hesketh created another company, Hesleydon (an anagram of Hesketh, Horsley and Gaydon), to manage the new venture, exactly six months after the collapse of Hesketh Motorcycles. A limited export production run helped to generate much-needed revenue, which was underpinned by regular work developing and applying EN10 modifications. When both of these markets began to tail off after a few months, Mick and his team pinned their hopes on a small-scale brand relaunch with the V1000 Vampire. Sadly, the new model was not a sales success and few were built before Hesleydon, too, ran out of money.

The Vampire was much criticised for its looks in 1983, but the intervening years have been kind and we are much more used to seeing enclosed tourers on our roads today. I borrow Mick’s personal mount, which he uses as a development bike, and really appreciate the John Mockett-designed full fairing on a day of unremitting drizzle. The frame-mounted GRP bodywork works aerodynamically, too, offering greater stability and lighter steering than the bikini-faired roadsters.

The Vampire was much criticised for its looks in 1983, but the intervening years have been kind and we are much more used to seeing enclosed tourers on our roads today. I borrow Mick’s personal mount, which he uses as a development bike, and really appreciate the John Mockett-designed full fairing on a day of unremitting drizzle. The frame-mounted GRP bodywork works aerodynamically, too, offering greater stability and lighter steering than the bikini-faired roadsters.

Lord Hesketh withdrew his interest in building motorcycles during the summer of 1984, but Mick used Hesleydon’s remaining assets to continue trading as Broom Development Engineering (BDE). In 1991, he completed a prototype of a radically different type of Hesketh. “The V2 Vortan was my version of the V1000 without any Eastern influence,” he explains. “I wanted it to look small and low, its long-stroke 1100cc engine appearing as big as possible. The name comes from Wotan, an operatic character that I misheard on the radio.” Ironically, the Vortan’s virtues were best summed up by Italian designer Miguel Galluzzi, talking about his own minimalist Ducati Monster creation, which captivated the Cologne Motorcycle Show a year later: “All you need is a saddle, tank, engine, two wheels and handlebars.”

Meanwhile, Lord Hesketh went on to hold political offices under successive conservative governments and on 13 July 2005, sold part of his Easton Neston estate to Russian-born entrepreneur Leon Max. The new owner required Mick Broom to vacate the stable block where he had worked for the previous 26 years, a blow amplified when thieves plundered packing crates containing tools, spares and irreplaceable records during relocation to nearby Turweston Airfield, near Brackley. Moreover, Mick was still short of the 15 orders that he needed to make production of the Vortan viable, so the following year he made another statement by transplanting a bored-out Vortan engine into a modified V1000 chassis, to create the 1200cc Vulcan.

Meanwhile, Lord Hesketh went on to hold political offices under successive conservative governments and on 13 July 2005, sold part of his Easton Neston estate to Russian-born entrepreneur Leon Max. The new owner required Mick Broom to vacate the stable block where he had worked for the previous 26 years, a blow amplified when thieves plundered packing crates containing tools, spares and irreplaceable records during relocation to nearby Turweston Airfield, near Brackley. Moreover, Mick was still short of the 15 orders that he needed to make production of the Vortan viable, so the following year he made another statement by transplanting a bored-out Vortan engine into a modified V1000 chassis, to create the 1200cc Vulcan.

The sole Vulcan prototype is not yet road registered, but Surrey-based enthusiast Tig kindly lends me his British racing green V1000 for a comparable riding impression. Tig’s bike was hand-built at Easton Neston in 1997 and incorporates most of the improvements that Mick has bestowed upon the Vulcan. Perhaps the most significant of these is a crank-mounted computerised ignition system, matrix-mapped to cover the entire rev range. Optimised combustion for each cylinder, combined with a heavier flywheel and an improved friction material in the clutch, has smoothed the transmission to such an extent that dual-step gearbox dogs are no longer needed and have been ground off. The rear cylinder runs more quietly, as it benefits from additional oil cooling to prevent overheating, while an additional bolt between the cylinders keeps the crankcase joint oiltight.

Riding a Hesketh with the latest EN10 specifications is a revelation. Gear selection is slick and precise, the meshed cogs remaining silent even at very low revs. A big handful of midrange throttle in top gear brings up 100mph at just 6000rpm, somewhat in the manner of a modern Triumph Thunderbird Sport. Adjustable Kayaba front forks and Maxton rear units make light work of surface imperfections, while six-piston front brake calipers and twin Spondon floating discs perform as well as they look, aided by 17in radial tyres on wide, spoked wheels with alloy rims. Vampire-derived seat rails make low-speed manoeuvres less precarious and the tubular swinging arm is braced for stiffness, though the long wheelbase is unchanged. The exhaust system is as fitted to the Vulcan, but cut down to fit the short-stroke engine’s exhaust ports. Overall, the BDE-manufactured bike is much more responsive and fun to ride than an original factory model, though the essential engineering remains the same. I return, soaked from the rain once more but wearing a big grin, which Tig acknowledges with news that he has just placed an order for a new Vulcan.

Riding a Hesketh with the latest EN10 specifications is a revelation. Gear selection is slick and precise, the meshed cogs remaining silent even at very low revs. A big handful of midrange throttle in top gear brings up 100mph at just 6000rpm, somewhat in the manner of a modern Triumph Thunderbird Sport. Adjustable Kayaba front forks and Maxton rear units make light work of surface imperfections, while six-piston front brake calipers and twin Spondon floating discs perform as well as they look, aided by 17in radial tyres on wide, spoked wheels with alloy rims. Vampire-derived seat rails make low-speed manoeuvres less precarious and the tubular swinging arm is braced for stiffness, though the long wheelbase is unchanged. The exhaust system is as fitted to the Vulcan, but cut down to fit the short-stroke engine’s exhaust ports. Overall, the BDE-manufactured bike is much more responsive and fun to ride than an original factory model, though the essential engineering remains the same. I return, soaked from the rain once more but wearing a big grin, which Tig acknowledges with news that he has just placed an order for a new Vulcan.

“The main difference in performance between the engine types is torque,” says Mick over a cuppa in his office. “The overall design was never about top speed, so the Vulcan is very much what the V1000 should have been all along. At this stage, after developing the EN10 modifications for so many years and putting them into practice, I see great potential for someone to produce the Vulcan for today’s market, as a modern British classic with real history. Now that I’m 65 years old, I’d like to retire at a point where I could still offer practical input to a commercial buyer for the whole Hesketh business.”

'…without his involvement, the Hesketh motorcycle would have been, at best, a short-lived historical footnote. Even its critics admitted that the bike had potential and there is a recurring sense of underachievement following the first V1000 launch'

Hesketh motorcycles without Mick Broom would seem unthinkable. As he leads me through the different engineering, storage and assembly areas of his modern industrial unit, I realise that without his involvement, the Hesketh motorcycle would have been, at best, a short-lived historical footnote. Even its critics admitted that the bike had potential and there is a recurring sense of underachievement following the first V1000 launch. But listen to Mick’s stories of testing a new gearbox under load by fitting a sidecar filled with cement, or pretending to be a tea boy in order to win over an intransigent supplier, and you realise that all along, he has quietly been getting on with the job of making the original design right. He has built around 100 additional Heskeths since the Daventry factory’s demise and at the time of writing has firm orders to build a further six. His manufacturing business is now for sale for a quarter of a million pounds, with good stock levels for four models (V1000, Vulcan, Vampire and Vortan) and a small but intensely loyal worldwide customer base.

With no prospect of the rain easing, I wheel the prototype Vulcan onto a runway at Turweston for a last photograph. Miraculously, its aviation namesake flies into view at that very moment, just visible beneath the low cloud. There’s no mistaking that distinctive profile and sound, which retain an evocative power. Both the Vulcan motorcycle and the V-bomber are the sole examples of their kind in current operation and each represents patriotic remanufacturing at its very best. With hindsight, therefore, it might seem apposite that the original Hesketh brochure should quote Christopher Fry’s noble line, ‘I know your cause is lost, but in the heart of all right causes is a cause that cannot lose.’ Mick allows himself a wry smile as he remembers why he chose the Hesketh cause over a rival opportunity, “Hesketh hadn't a clue what they wanted, but looked like they had a bit of money, whereas Norton knew exactly what they wanted but had no money. I went to work for Hesketh for three months in 1979 and in a sense I’ve never left.”

With no prospect of the rain easing, I wheel the prototype Vulcan onto a runway at Turweston for a last photograph. Miraculously, its aviation namesake flies into view at that very moment, just visible beneath the low cloud. There’s no mistaking that distinctive profile and sound, which retain an evocative power. Both the Vulcan motorcycle and the V-bomber are the sole examples of their kind in current operation and each represents patriotic remanufacturing at its very best. With hindsight, therefore, it might seem apposite that the original Hesketh brochure should quote Christopher Fry’s noble line, ‘I know your cause is lost, but in the heart of all right causes is a cause that cannot lose.’ Mick allows himself a wry smile as he remembers why he chose the Hesketh cause over a rival opportunity, “Hesketh hadn't a clue what they wanted, but looked like they had a bit of money, whereas Norton knew exactly what they wanted but had no money. I went to work for Hesketh for three months in 1979 and in a sense I’ve never left.” ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.