With lots of late 1960s and 1970s BMWs ending up as café racers this more authentic take, paying tribute to the beautiful Rennsport, makes a refreshing change.

Words and photography: IAN KERR

In 2014, Michael Dunlop, son of Robert and nephew of TT legend Joey, gave BMW its first solo class TT win since Georg ‘Schorsch’ Meier led home his teammate Jock West in the 1939 Isle of Man Senior TT.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

The first victory was at a record speed of 89.38mph and was on one of the factory-built, lightweight supercharged motorcycles, a replica of which was tested by Alan Cathcart in the January 2016 edition of this magazine.

The BMW 500 Type 255 Kompressor was one of the most sophisticated motorcycles of its time and were it not for the governing body’s – the FIM – postwar ban on supercharging, who knows how machines from the German firm would have progressed.

But certainly the S1000RR that Dunlop blitzed the mountain course on is a worthy successor, being one of the most sophisticated machines on sale at present, albeit not powered by BMW’s trademark ‘boxer’ engine.

In between these two events, of course BMW dominated world championship sidecar racing with a normally aspirated Rennsport motor from the middle of the 1950s to the end of the 1960s.

Not to mention Walter Zeller coming second in the 1956 500cc solo world championship on a type 256 Rennsport, although BMW withdrew from racing official works grand prix machines in 1958.

The Rennsport was one of the first racing motorcycle designs to come out of Germany in the postwar period, after the FIM allowed German machines back into the championships.

As supercharging was abolished on racing motorcycles, BMW had no choice but to modify its boxer engines and revert to two carburettors.

The dimensions of the cylinders were changed and the engine’s power and weight were different. The motorcycle’s total weight was around 275lbs, showing how much work was done by the factory on the first of the models, which appeared in 1953.

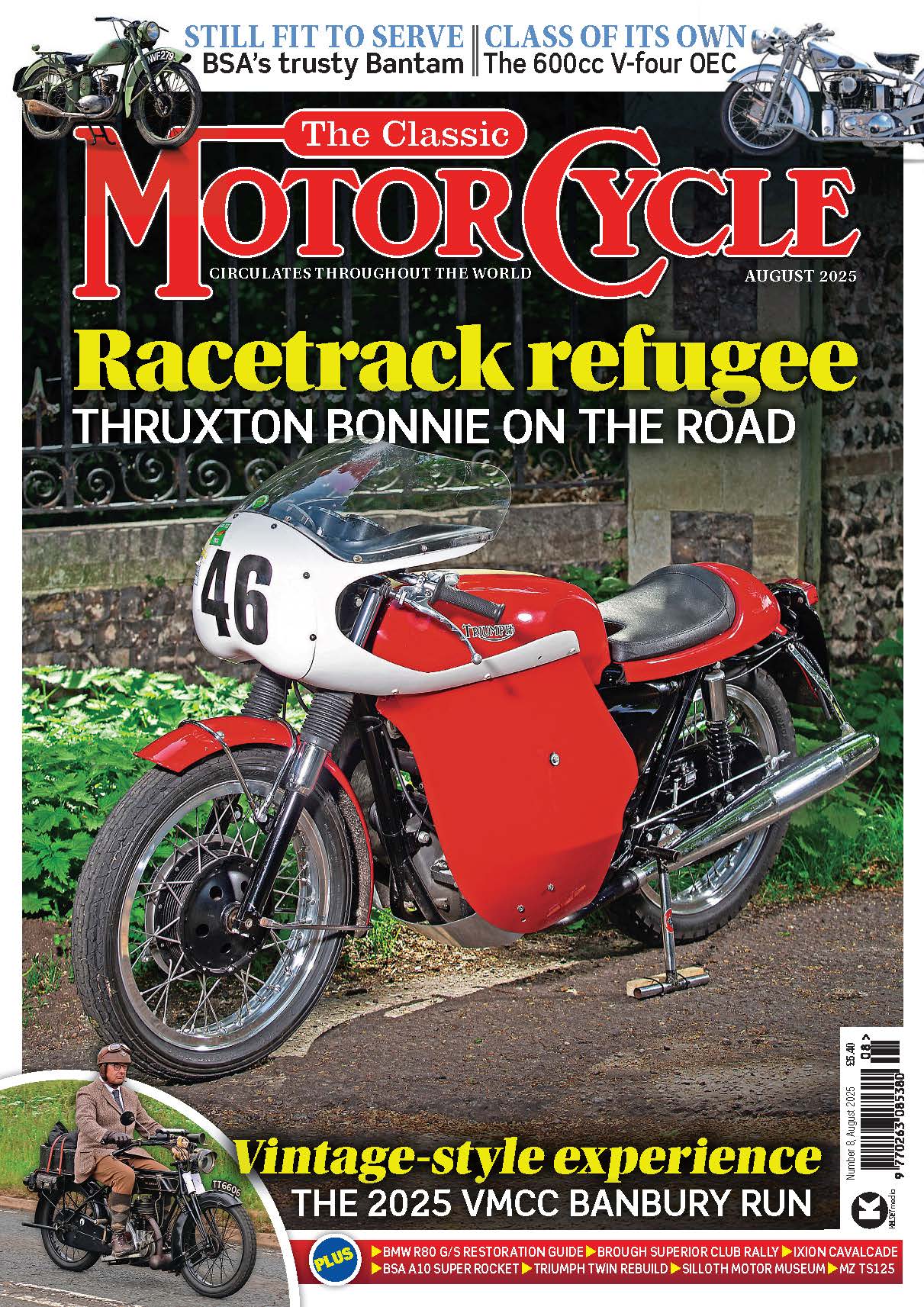

But the BMW pictured here is not a genuine Rennsport from that period. It started life as a standard 1971 R60/5 road bike.

But, at a quick glance, it could easily be one of the RS500 Type 256 from 1956, though without the beautiful aluminium Bartl-style ‘duckbill’ fairing, which was thought to split the airflow and improve the ‘slipperiness’ of the bike as a whole.

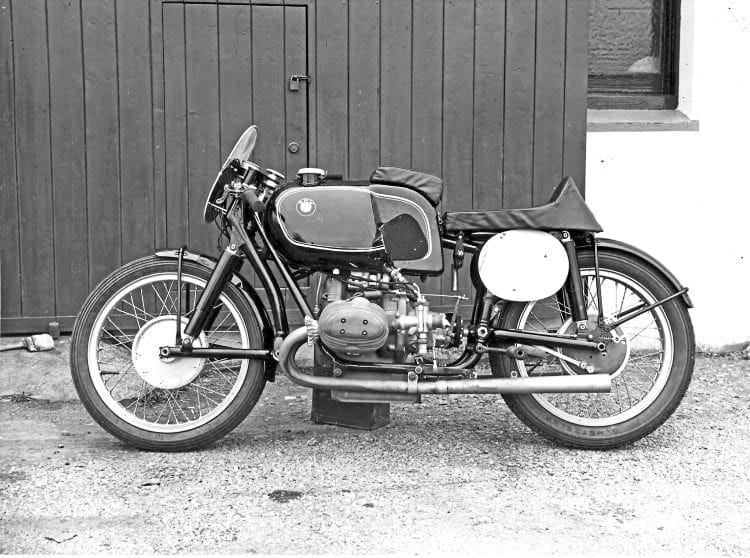

You may not agree, but it is said that beauty is in the eye of the beholder and it was that feeling that attracted Jason Blackiston of Anson Classic Restoration when he saw the Rennsport RS500 for sale at the H&H auction at Duxford last year.

However, an estimate in the region of £160,000-£180,000 meant it was never going home with Jason, but, as fate would have it, there was a very rough-looking BMW R60/5 in pieces on offer at considerably less…

“I don’t know why I bought it really,” said Jason, reflecting on the sad-looking BMW he took home, “I just thought I would rebuild the bike as standard and sell it on.”

But the image of the Rennsport was still burning away in Jason’s mind when he emptied the remains of the bike into the company’s workshop in Leicestershire.

Although mostly all there, the BMW was in need of some serious attention and the engine clearly needed a complete rebuild.

It was then that the idea of creating not so much an exact replica of the Rennsport, but more a tribute was formed between Jason and his workshop foreman, Mat Jones.

So, with a stunning detailed image of the Type 256 pinned to the wall of the busy workshop, the R60/5 was stripped down to all its component parts and those not needed for the project were put to one side for future use, or to sell off to offset costs.

The idea was to create a bike that could still be used on the road, so it had to be user-friendly, even if it did get the odd day out on a track from time to time.

Having said that, as Jason so ably put it, “I thought the world did not need another BMW café racer with a brown quilted seat and satin paint with an exhaust wrapped in asbestos string!” I think given the end result he has succeeded in producing something of quality and almost a work of art.

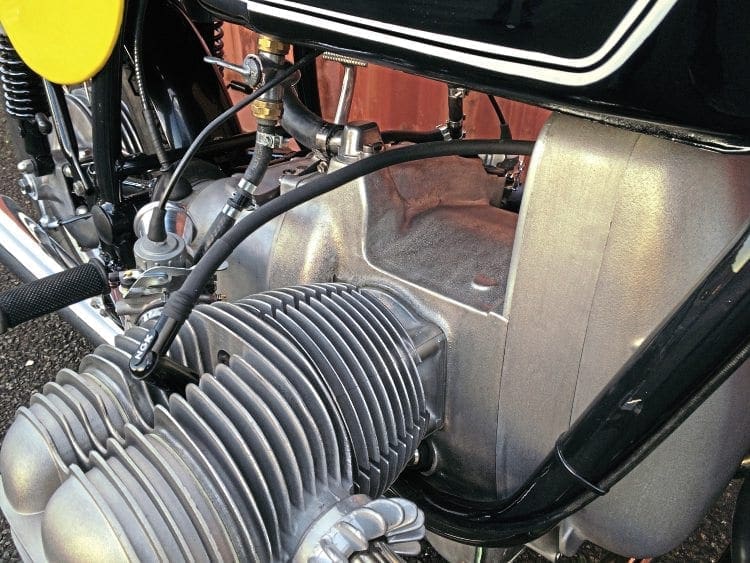

So, instead of investing thousands on trick internal components like the factory originals, the engine was just carefully rebuilt – after the crankcases had been substantially altered to give a silhouette similar to the factory bikes after removing the starter motor.

Careful cutting and welding took time, as did returning the aluminium to look the same as the rest of the casing, such is the attention to detail that has been lavished on this machine.

The gearbox and final drive were all dismantled, checked, and reassembled with all new seals and gaskets, but all remaining standard.

The frame too may have had a few lugs removed here and there, but, in essence, it remains standard and very different from the lug-less oval-section tubed item that graced the original Rennsports.

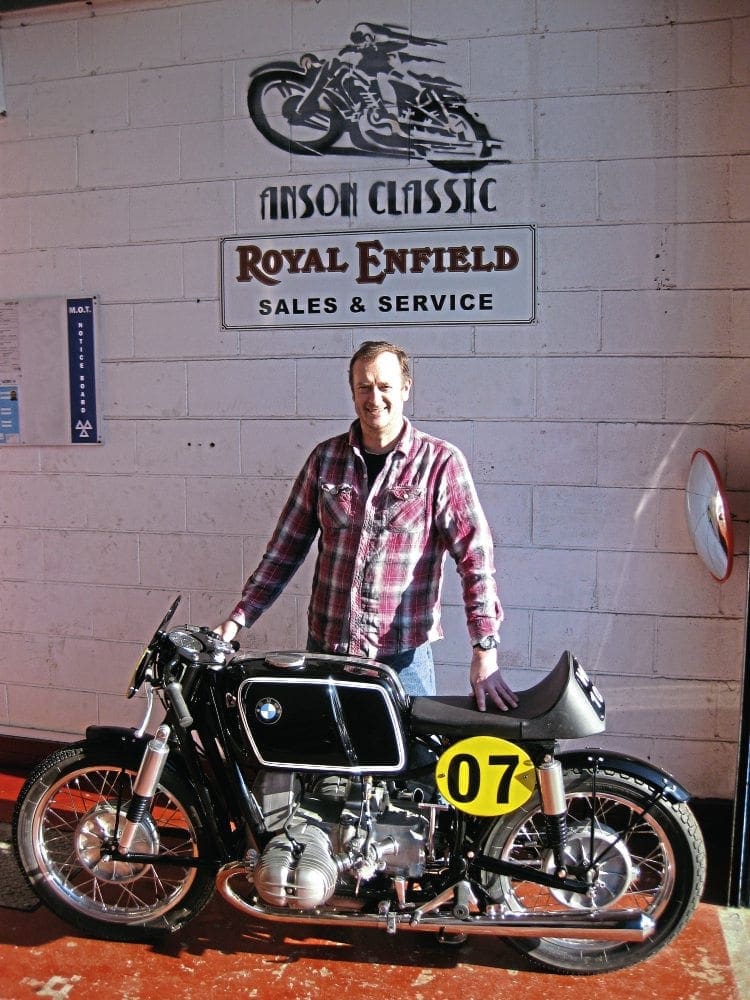

It goes without saying that all bearings and bushes were replaced on the frame as well as on the new leading-link front forks obtained from Germany, which needed some minor modification to fit in with the design.

The R60/5’s original telescopics would not have been right or correct as BMW had moved across to the ‘Earles’ type fork for racing, the Earles’ design being lighter and much stronger than traditional telescopic forks.

The fork was licensed from Englishman Ernie Earles after he patented the design in 1953, hence the name.

The original petrol tank was cut open, modified, and rewelded to give the desired look, along with the manufacture of a central retaining band.

Mudguard stays etc were fabricated in-house, as was the remarkably original-looking seat unit.

A lot of the bracketry and linkages had to be made from scratch, as did the clever rear numberplate holder and fly-screen.

One of the nicest touches is the moulding of the original combined speedometer/rev counter into the design, sitting almost unobtrusively behind the fly-screen and just in front of the neat steering-damper knob.

Jason has tried to use as many parts of the donor bike as possible to keep down costs, but some new parts – such as the slim mudguards – were bought in, as there was no point in spending time making them.

The exhaust system is another prime example of a bought-in component, but the stainless steel and chrome Hoske-style silencers are worth every penny, looking period and sounding just right.

The wheels were fully rebuilt with stainless spokes, new tyres and tubes and all cables and rubbers were replaced.

Initially, a new Boyer Bransden electronic ignition was fitted along with new coils, loom and battery and solid state regulator rectifier (cleverly hidden under the tank) although this has now been removed and the original points system reinstated, to ensure easier starting.

The Bing carbs were replaced with modern Mikunis as the originals do not like running unfiltered and it is difficult to set the engine up to run and pull cleanly, even when hot.

Once the dry build was complete the frame and forks were treated to a two-part powder-coat system. The rest of the tinware got sprayed with a two-pack base coat before being lacquered to give a deep quality finish similar to 1950s BMWs.

The overall appearance of the finished motorcycle is stunning, and I am sure that if the bike were to be parked in a race paddock, it could easily pass off as original, until a detailed inspection took place.

Certainly it sounds as good as an original, if a little quieter, but the big plus with this bike is that it is road legal for daytime UK use and comes with a current MoT.

It may not have the short-stroke engine with all the trick lightweight internal components, or the five-speed gearbox, but it is a very usable bike that will provide hours of reliable fun on the road as well as attracting many admiring glances when parked up.

Quality abounds, as does craftsmanship!

“Now we have built this and worked out how to fabricate the various bits and pieces, we can build a few more and cut down on the time and therefore labour cost of the build”, said Jason.

“Although it is more a tribute than a replica, I have had no shortage of interest and sold it within days of finishing it and I am now looking at building a few more ‘racing’ BMWs as there seems to be quite a demand,” he concluded as we stood admiring the bike in the winter sun.

I know what he means, and I have already put my name down for a future recreation as, like him, I think that the Rennsports are one of most beautiful bikes ever to come out of Germany.

Now, thanks to Anson Classic Restoration, more of us can at least experience the flavour and essence of the bike without mortgaging the house and be able to just go out and enjoy it on a sunny day without needing a nearby race track!

www.ansonclasisic.co.uk or 01509 502534.

The best BMW cafe racer ever?

When racing legend Walter Zeller retired from top-level racing at the end of 1958, he left with this incredibly special machine, constructed to his own specification.

It used a 600cc, 60bhp supercharged engine, dated to 1949 and built for sidecar racing, housed in a Rennsport-type frame. Interestingly, Zeller chose telespcopic rather than the Earles-type forks he’d also raced with – some reports reckoned he preferred ‘teles’ though there is also a suggestion that the Earles’ forks wouldn’t clear the blower.

Front wheel is from a Rennsport, though the silencers come from the standard road catalogue. Lights were total loss and there was no kick-start fitted.

Zeller had fully expected to buy the motorcycle, which he’d kept an eye on as it was constructed, to his specification, in the test shop, and was a regular visitor during its build to ensure everything was tailored to suit him.

When the machine was finished, BMW’s management arranged a ceremony to hand the machine over – which they did, as a gift, and much to Zeller’s surprise.

After racing, Zeller worked in the family business and with things not going as well as they could, he sold the machine in 1963 to a schoolteacher, who’d apparently telephoned every month for years requesting the opportunity to buy the machine.

The price was supposedly 7000 Deutschmarks, which is more than £2800, at a time when a Triumph Bonneville cost about £320.

Read more News and Features at www.classicmotorcyle.co.uk and in the latest issue of The Classic Motorcycle – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.