The seamy world of fakes, replicas and specials is one which can be navigated when armed with an understanding of what constitutes those terms, as well as a bit of nous to ensure you’re not being taken for a ride.

Words: MICHAEL BARRACLOUGH Photography: MORTONS ARCHIVE

While it may be an ugly topic and not one that many classic motorcycle devotees like to spend much time thinking about, it is an unfortunate truth that there are some insalubrious characters out there in the world that view classic motorcycles more as a way of making a few bob than as meaningful, pleasurable pursuits.

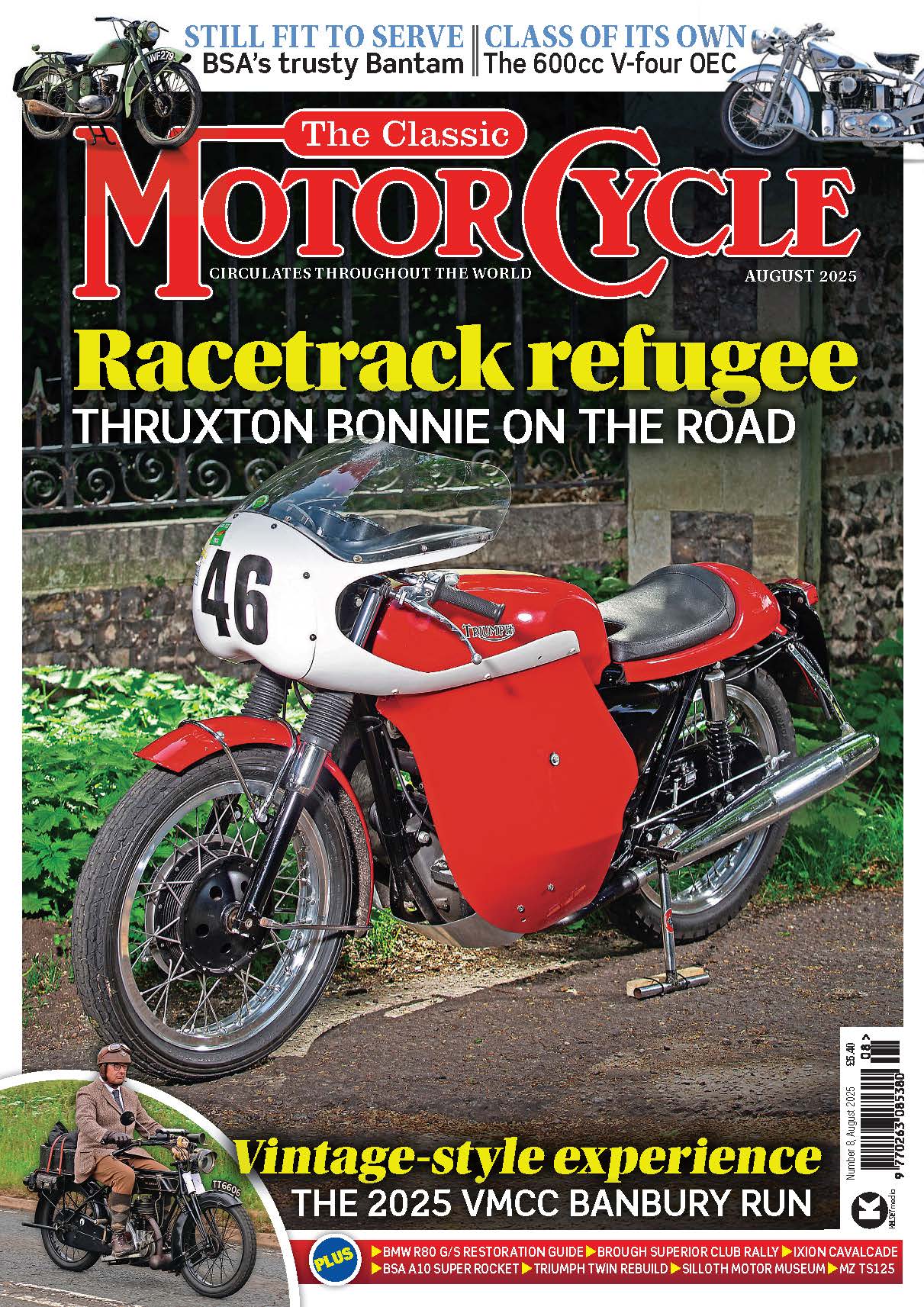

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

There are several patches of ambiguity that cause unwanted confusion and obscurity (such as what happens to the value and provenance of a historically significant machine when you introduce replica components, and vice versa) and these abstruse areas are occasionally utilised as convenient cover by some, who will ‘embellish’ certain machines and make them rather more worthy than in fact they are.

Eligibility throws yet another spanner into the works as some events only allow bikes of a certain age to participate, and age and eligibility equate to value in the eyes of many, meaning that sometimes a motorcycle is presented as being older than it actually is.

These areas provide a prudent place to begin understanding why this sort of activity occurs, and the key is being able to draw the distinction between what constitutes a replica, a fake and a special.

The dictionary definition of a replica is ‘an exact copy’ and so, with that definition in mind, any motorcycle that has been fabricated from spares, NOS parts or similar that has been made to resemble a famous or desirable machine can be classed as a replica.

The whole situation starts to become confusing when original components enter the picture, and some believe that, if you have enough original components in a replica rebuild, then the machine in question can straddle that tenuous boundary between ‘replica’ and ‘genuine article’ which simply is not the case.

The inclusion of the odd original or period component might add an extra layer of intrigue to the replica which may even equate to increased value if the bike in question is sufficiently impressive but, crucially, the machine is still a replica and must be advertised and displayed as such if the owner of said replica is to avoid the murky waters of vehicular fraud.

Auction houses are very careful when considering machines for upcoming auctions and can remove suspect motorcycles in advance of their consignment to auction if they have reason to believe that something might be amiss, and the correct frame and engine numbers are crucial – more on this subject later.

Popular replicas include the Manx Norton and the Matchless G50, both of which regularly appear in classic race meetings for 500cc singles.

An interesting addendum to this short section about replicas is that some marques from days gone by did produce in-period replicas of famous race winners that the public could go out and buy – Yorkshire manufacturer Scott was one such marque.

A special is a much more straightforward term to define and describe.

Stick a Vincent V-twin in a Norton Featherbed frame with the appropriate cycle parts and you’ve got yourself a Norvin. Put a Triumph 650cc twin in the same frame and you’ve got a Triton.

The notion of the ‘special’ revolves predominantly around the combination of engine and frame, as is well known, and as long as it is advertised and displayed accordingly with no information omitted or falsified then no legal ramifications should follow.

Machines that have been stylistically altered to fit a certain aesthetic can all also be viewed as specials. Bobbers, choppers and café racers all fall under this banner.

A fake, then, is a motorcycle which has been made to look like something else in order to deceive prospective buyers into believing that it is a different (often more valuable) machine.

There are many classic motorcycles that have proven to be popular targets for this kind of fraudulent activity.

It would probably be fair to assume that more than one of our readers has heard a story concerning a purportedly fake Rocket Gold Star over the years that they have been entrenched in ‘the scene’, as the rorty Rocket Goldie seems to be one of the more popular counterfeits and many Rocket Gold Stars (authentic or not) have been accused of being ‘fakes’.

Typically people with the inclination to create a fake Rocket Goldie will get hold of another early-1960s A10 Beezer – a Super Rocket, for example – then strip it down, repaint it and reconfigure it into a replica Rocket Goldie.

Add the siamesed exhausts that were a factory optional extra for the Super Rocket but came as standard on the Rocket Goldie, and you’ve got a bike that, cosmetically at least, looks uncannily like a Rocket Gold Star (though there are subtle differences that will identify a genuine Rocket Goldie frame).

In the Triumph camp the humble Thunderbird or TR6 is occasionally known to disappear into a dark shed and emerge weeks later as a Bonnie (normally one of the highly-prized early-1960s models) though this, thankfully, seems to be less prevalent than it was.

Things become more difficult for the fakers and forgers as you turn back the clock, especially when you slide past the Second World War and into vintage country, though that’s not to say that the odd bike won’t occasionally slip through the net.

Where the sleek vintage and post-vintage bikes dwell a more insidious tactic exists.

This tactic focuses less on trying to physically build a valuable bike out of a more run-of-the-mill machine and instead puts the emphasis on harnessing mystery and folklore to increase the provenance of a pre-existing motorcycle, thereby making it more desirable and, consequently, more valuable.

It isn’t too difficult to imagine somebody building a convincing replica of an old TT-winner (or simply tweaking a standard model of the same type) and then trying to sell it off as the genuine article.

Dennis Frost is chief judge at the Stafford show and historian of the LE Velocette Club, and he explains that, while fake motorcycles do exist, they rarely find their way to nationally-renowned events.

“The Stafford judges are rarely presented with fake machines,” Dennis says “and I am blessed with heading a fantastically experienced team, but if we are not sure about a particular entry we seek a second opinion.”

I alluded to problems caused by eligibility earlier in this feature, and that is a subject worth expanding on.

Some classic bike aficionados, fuelled not by greed or any other insidious motive but rather by their passion for riding old bikes, might choose to tell a white lie to get themselves into events which implement certain criteria upon their entrants, usually pertaining to the age of participating machines.

The forethought might be innocent enough; Mr Bloggs might want to ride his 1916 Triumph in his local pre-1915 run and as it does look very much like a 1914 model, he decides to fudge its age in order to ride.

It’s quite easily done, as the commencement of the First World War did stymie development. While this sort of conduct could be viewed by some as harmless, it is just injurious enough to start confusing records, and that will only cause more ambiguity further down the line.

Many motorcycles which come under the category of ‘fake’ are sold privately, as the sellers don’t want to risk entanglements with auctioneers who can (and will) take a very close look at the machine to ensure it is genuine, though some do find their way into the auction process.

Thankfully they are often rooted out and removed. Many auctioneers of classic motorcycles will screen all prospective entries and run the frame and engine numbers (as well as anything else that is indicative of fakery) past the relevant marque specialist or owners’ club, should they find something that strikes the inspectors as ‘out of place’.

Auctioneers always look to make sure that there is no misinformation anywhere along the line, and that what is described in the catalogue is exactly what gets sold when the hammer drops at auction. This is no more important than in the case of replicas and recreations.

When it comes to verifying what is genuine and what is not, frame and engine numbers have always been the most definitive way of sorting the real from the bogus.

In Great Britain, a motorcycle stands or falls by its frame number and, legally, this is the principle form of identification for an old bike. This is where all serious forgeries begin.

Vincents, interestingly, have an advantage over most other old bikes in that there are several numbers stamped or die-cast into the frame which are unique to each motorcycle, making it much trickier to fabricate a convincing fake.

According to Dr Ken German, who was formerly in charge of the Metropolitan Police Stolen Vehicle Squad and is still actively involved in the prevention of vehicle crime, a false frame number can cause a plethora of problems for the classic bike owner. It could be that the bike you are looking at is, in fact, one of the 720 classic machines (that the police know about) that have been stolen in Europe this year.

There are several ways that you can test whether the frame number on your motorcycle is genuine.

Back in days of yore, the vast majority of motorcycle manufacturers used to spray over the area where the VIN numbers were stamped with paint, and during the manufacturing process this paint was nearly always baked on.

If there is no paint on the area of your frame where the VIN number has been stamped then that could be a cause for concern, though even if paint does remain it is possible that a similar paint in the form of an aerosol cellulose spray has been applied to ‘make good’ the area.

A useful trick, if you think something might be amiss, is to wipe a cloth soaked in a little acetone (nail varnish remover) over the painted surface where your VIN number is located.

If the paint comes away very easily, it could be indicative of foul play. Acetone will not remove the ‘baked on’ paint no matter how much elbow grease you apply.

Discrepancies in the size and font of the characters in your frame number can also be telltale signs of skulduggery, though thankfully many of the owners’ clubs possess a lot of factory records that can help explain any inconsistencies that you might discover.

Taking all of this information into account, a hypothetical scenario (illustrated on page 35) comes to mind.

Take, for example, a Manx Norton from the 1950s that won the Senior TT during that decade.

If the motorcycle was disassembled after its victory and separated into three different elements (the frame, the engine and the cycle parts) and then these three elements formed the basis of three separate restorations, which one could be classed as the one that won the TT?

From the perspective of the auctioneer, the answer is none of them. The auctioneer would have to describe the restorations as standard motorcycles that were simply ‘incorporating the TT winning frame’ and ‘incorporating the TT winning engine’.

It is likely that the restoration with the cycle parts would simply be viewed as a standard motorcycle as these are not deemed as important as the frame or the engine.

The Vincent Owners’ Club Spares Company used its vast resource of parts to build a completely new Black Shadow in 2007.

This was unique in that it was built using newly-manufactured components supplied by the Vincent Owners’ Club Spares Company and as such was not eligible for an age-related number as it was a brand new motorcycle, so the VOC had it registered as such.

So, is the sort of nefarious behaviour highlighted in this feature increasing?

Evidence says, yes, it certainly seems that way. More and more people are buying classic motorcycles but they are buying them primarily as an investment, not as a provider of riding pleasure, and this is one of the factors pushing the monetary value of classic bikes up (compare the price of a Brough Superior SS80 sold 10 years ago with the price of one now) and there is also, according to Dr Ken German, a problem with organised crime gangs who are getting better at telling a valuable classic from a not so valuable one – unwelcome news for the classic motorcycle owner. Still, it helps to arm oneself with information and, once you know what you’re looking for, a ‘ringer’ can be spotted a mile off.

SCOTT REPLICA

The ‘TT Replica’, as it was designated, was first introduced at the end of the 1928 season and was essentially a replica of the motorcycle on which Tommy Hatch rode to third place in the Senior TT earlier that year.

It was available in 498cc or 596cc versions and became very popular, lasting for several years in the Scott roster. The fact that you could go to your local Scott dealer and purchase a machine that was more or less identical to one that placed third in the Senior TT was quite the draw for prospective owners, and a clever bit of marketing from the folks at Scott.

The problems start to arise when one considers that these machines are, due to their popularity and race-bred style and performance, rather valuable, and consequently become a target themselves.

It all starts becoming very convoluted when you entertain the notion that somebody could be out to make a fake replica of a TT Replica! This model – a genuine replica, if one can have such a contradiction in terms – sold at auction several years ago.

VINCENT GREY FLASH

Based on a Vincent Comet, this is an example of a replica done really well. Not only does it look like a Grey Flash, but the individual components and, as a result, the performance are very much akin to that of a genuine Flash.

Crucially, this replica has never purported to be any other than a lovingly-crafted recreation of a famous postwar single.

Only 31 complete Grey Flash models were ever built by the Stevenage-based factory, so a replica is about as close as many can get to owning one of these stellar machines.

This causes a problem for the fakers and forgers of the world as, with so few of them built, it would be near-impossible to fabricate one that would fool the many experts who possess a wealth of information concerning these machines.

BSA ROCKET GOLD STAR

This Rocket Gold Star has been looked over by the experts and it has been confirmed that, though it does look uncannily like a genuine Rocket Goldie (minus the clip-on bars that you see so many of these bikes sporting, though the ace bars are technically the correct factory spec), this one is, in fact, a lookalike.

It’s a sad tale, but one previous owner was sold this machine under the guise that it was genuine (before it was confirmed that it was a replica) and the aforesaid owner may well have had to pay genuine Rocket Gold Star money for it.

This is a sobering example that the sort of activity described in this feature is actually happening.

THRUXTON VELOCETTE

This Thruxton Velocette is unique in that it incorporates a TT winning engine. It was correctly and responsibly sold as a machine ‘incorporating the TT winning engine’ and not as the genuine TT winner, which would have been considered fraudulent.

Some motorcycles incorporating an original, authentic engine have been occasionally known to masquerade as ‘the real deal’ in the past.

Only if the original frame was part of the same restoration alongside the original engine could the authenticity of the machine be properly confirmed.

Cycle parts don’t seem to carry quite as much magnitude – as one might expect – and are often disregarded altogether.

A Norton incorporating the seat on which Geoff Duke rode to victory in a GP event, for example, would likely not warrant any special consideration and the seat might not even be mentioned in the catalogue description of the motorcycle.

Read more News and Features at www.classicmotorcyle.co.uk and in the latest issue of The Classic Motorcycle – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.