It was during a stint on the Mortons stand at the Birmingham NEC’s when the affection held for Vincents manifested itself. Our stand was in the Classic Village, directly opposite the 15 competitors for the Carole Nash/Classic Motorcycle Machine of the Year.

This fine selection of machines ranged from a vintage James vee-twin to a mid-Seventies Kawasaki trials iron but also creating a stir was the machine on our own stand – a 1951 Vincent Black Shadow 1000cc vee-twin.

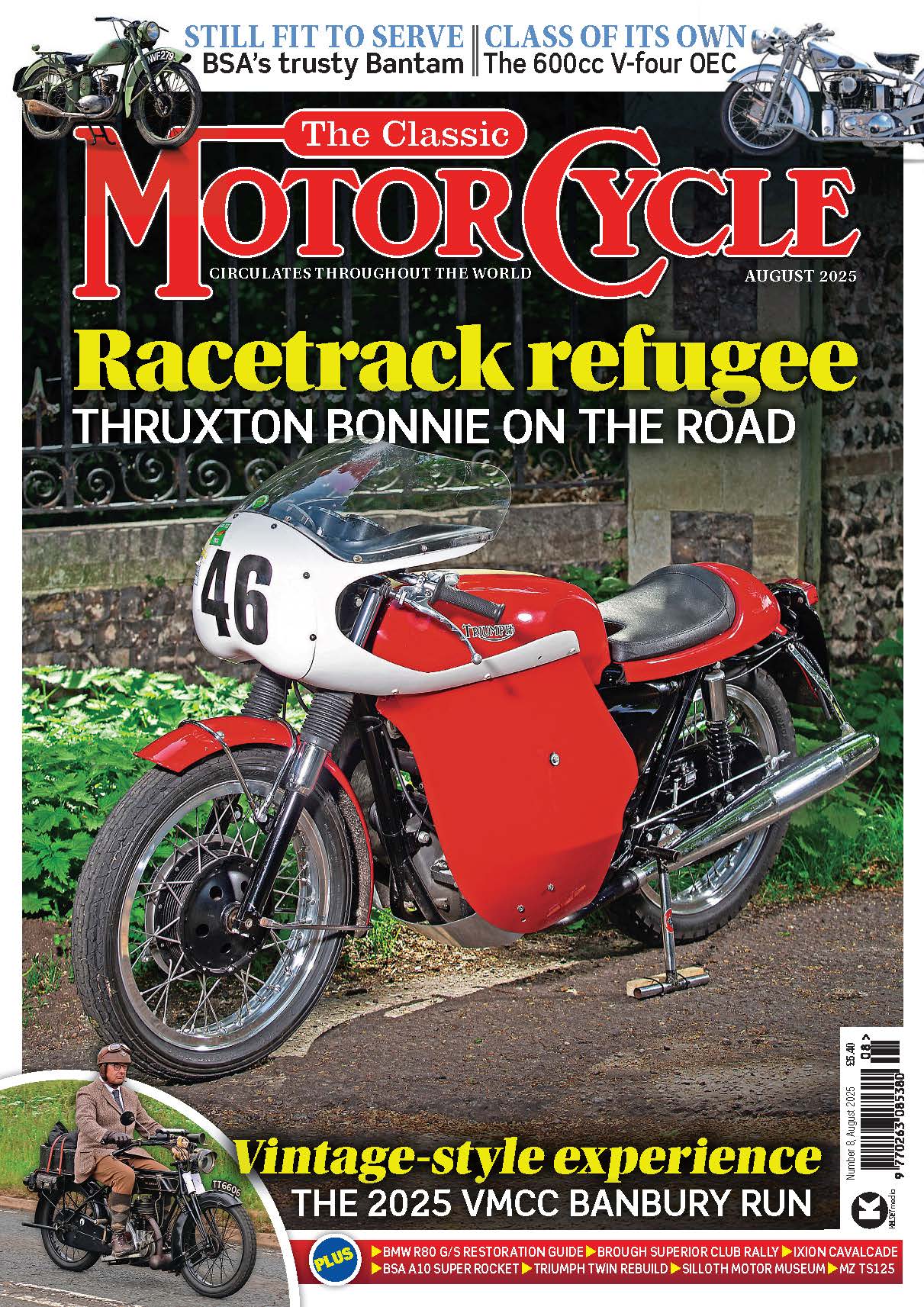

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Many modern bikers stared longingly (or inquisitively?) at arguably the Stevenage firm’s finest product, the Black Shadow, holding its metaphorical head high and looking as purposeful as ever in its moody black and gold lined livery.

“Did it really do 125 mph? In 1951? On those tyres!” was the incredulous cry from many a visitor clad in his Dainese leathers and Sidi boots.

When I informed them that some mad bloke had ridden its even faster stablemate, the Black Lightening, to over 150 mph on Bonneville Salt Flats clad only in his swimming trunks they thought I was joking. I wasn’t, Rollie Free did in 1948.

Vincents were tuned-up to even more startling feats over the next 25 years, culminating in the performance of Brian Chapman and his single cylinder Comet-based sprinter. Tagged ‘Mighty Mouse’, it covered the quarter mile in 8.81s, a time that shamed many younger, larger capacity machines.

Vincents were tuned-up to even more startling feats over the next 25 years, culminating in the performance of Brian Chapman and his single cylinder Comet-based sprinter. Tagged ‘Mighty Mouse’, it covered the quarter mile in 8.81s, a time that shamed many younger, larger capacity machines.

Other visitors had stories aplenty about Vincents they still own. One chap had owned his Series A Comet since 1946; a Welshman had 12 (eight big twins and four singles); another wanted to know who had restored our Shadow because he’d had one in his shed for 31 years which should have something done about it.

A modern bike rider’s father had kept a twin in the shed for years and done very little with it. And a man from Essex had just returned to motorcycling after a long break and bought a Series B version of the twin.

Then came the inevitable comments, “I used to have one but sold it when…” Five or six people told me they had sold them for figures ranging between £50 to £400.

They had all sold them out of necessity – expanding families and the need for four wheeled transport. All looked wistfully at the pristine Shadow and sighed, “I wish I still had it now…”

In the beginning

Philip Vincent started his company in 1928 with a sprung-framed, proprietary-engined machine that was designed to give a ride vastly superior to the rigid framed competition. He decided not to introduce his radical product under his own name but try to benefit from a name already familiar to motorcyclists.

He duly bought the HRD name (formerly the property of TT winner Howard R Davies) and set about selling his product. In 1935 an in-house designed engine was introduced followed by the legendary vee-twin motor.

This apparently came about when Phillip Vincent happened upon two drawings that Australian designer Phil Irving had put on a drawing board of the single cylinder engines overlaying each other. He saw the potential and decided to build the vee-twin.

Despite awesome performance for the day (a standard Series A Rapide lapped Brooklands at 106.65 mph before WWII), the big HRD was producing too much power (about 45 bhp) for the bought-in Burman gearbox and clutch to cope with.

After the war, Phil Irving and Vincent himself set about making a more refined version of the Rapide. Introduced in 1946, the new incarnation was to become a motorcycling legend. The new Rapide was a much neater version of the pre-war machine, with a gearbox and clutch designed by Vincents themselves.

The new model also dispensed with a frame, utilising the engine as the main stressed component. This B model retained the pre-war bought-in Brampton forks and was capable of a genuine 110 mph on the poor quality pool petrol of the day. But the cost of being undisputed ‘King of the Road’ was £300 at the end of 1946, when £167 would buy a Speed Twin Triumph or two brand new Matchless G80 500cc ohv singles.

America was an important market in those post-war days and the HRD was a popular export. But some were confusing the HRD moniker with that of Harley-Davidson and so, in about 1949, HRD became solely known as ‘Vincent’. Meanwhile, an even higher performance version of the Rapide, the Black Shadow was launched, two single cylinder models, the Meteor and the Comet, had also joined the range.

The latter were basically twins with the rear cylinder removed (ironic, considering the original conception of the first twin) and both used a Burman gearbox so drive to the rear wheel was on the opposite side to the twin.

Vincent went on to introduce a fully faired-in version of the twin, deemed so futuristic that they were chosen transport for ‘The Thought Police’ in a Fifties film version of Orwell’s novel, ‘1984’.

By then, however, the company was on a downward spiral and by 1956 production was over.

Advanced design

Advanced design

The attraction of a Vincent is its initial dramatic, but understated, appearance. Look closer and you start to notice the features that made the machine so advanced; the lack of a traditional frame, the modern style cantilever rear suspension, the semi-unit construction engine, Vincent’s own ‘Girdraulic’ forks, the dual brakes, the oil-bearing centre ‘spine’.

The problem with the superbly (over?) engineered Vincent was the cost of building it, both in terms of money and time. Some indication of the time taken to build a Vincent is this comparison.

At the peak of Honda production, the Japanese firm produced in one hour more motorcycles than the Stevenage firm ever produced – 16,000 from Honda in an hour compared to approximately 13,000 Vincents between 1928-56.

As an example of the Best of British though, I think that the Black Shadow takes some beating. Although it has had its critics, many owners have wracked up huge mileages on the machines.

For innovative thinking, astounding performance for the period and the fact it looks so good, the Black Shadow remains near the pinnacle of classic machinery. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.