The popular image of Harley-Davidson as being a manufacturer solely of large-capacity 45 degree V-twins with ‘potato-potato’(TM) exhaust notes is wide of the mark. Although aficionados are keen to celebrate the firm’s 2003 centenary, some might prefer to develop selective amnesia about the past. The company’s previous offerings include such utilitarian delights as the Topper scooter, famously likened to a breadbin on wheels, and the almost indescribable Shortster (yes, really). In the immediate post-war period H-D also availed themselves of the same set of DKW blueprints that turned into the BSA Bantam, christening their version the Hummer. Even more embarrassing, the hall of shame includes the long-running Servicar three-wheeler, a sort of low-tech Reliant Robin, minus the upper body shell.

Of more relevance here, the men from Milwaukee also put their badge on a moped! Having axed the Topper scooter in 1965, the management reckoned that Americans would want to spend $225 on a 49cc runabout. As it happened, few did, so in 1972 the M-50 was consigned to a dark corner along with the Hummer, Topper and Servicar.

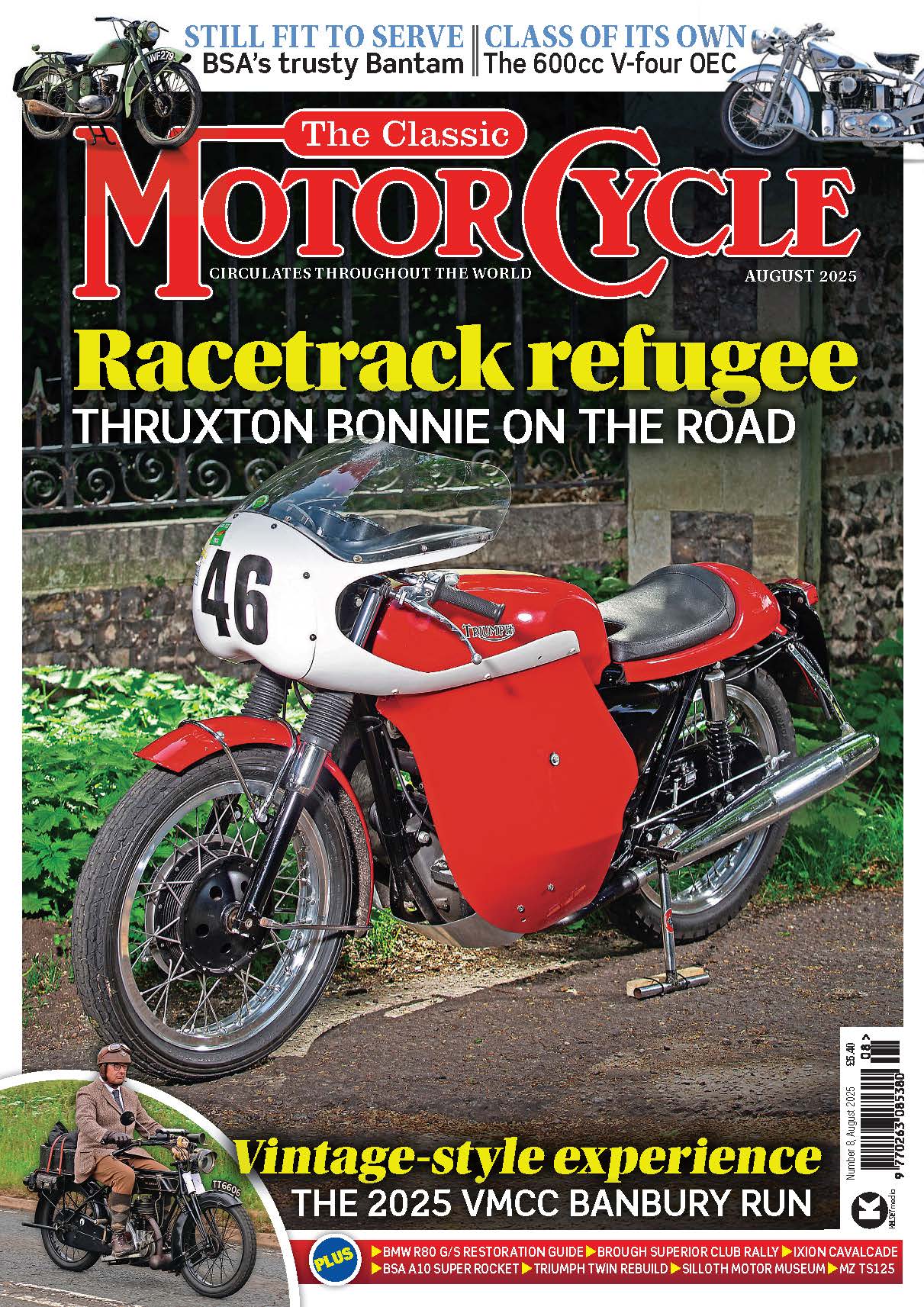

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Most of the lightweights like the M-50 and M-65 were actually made in Varese, Italy, rather than the USA. In 1960, Harley badly needed something smaller than the lumbering V-twins and had taken a 50 per cent stake in Aermacchi, whose wares included a range of sub-quarter litre two-wheelers.

Most of the lightweights like the M-50 and M-65 were actually made in Varese, Italy, rather than the USA. In 1960, Harley badly needed something smaller than the lumbering V-twins and had taken a 50 per cent stake in Aermacchi, whose wares included a range of sub-quarter litre two-wheelers.

Like several other motorcycle and car manufacturers – BMW being perhaps the most famous example – Aeronautica Macchi started life making flying machines. After the dust of WWII settled, they weren’t allowed to make anything with military potential, so instead turned to the business of mobilising the masses. Lino Tonti, who tends now to be associated chiefly with later work with Moto Guzzi, was responsible for the early designs, but the distinctive ‘horizontal’ four-stroke singles were designed by Alfredo Bianchi.

Later variants

The first 175cc Chimera wasn’t a huge success for them, but later variants went on to win races and break speed records. By the time Harley came on the scene, the capacity was up to 250cc (a measly 15 cubic inches in Milwaukee-speak), and the bikes were as good as anything on the market – with the possible exception of the new breed of Far Eastern dream machines.

I don’t want to mention the ‘H-word,’ but it’s perhaps amusing that one of Aermacchi’s greatest hits was the CRTT Ala d’Oro racer. In case you don’t have an Italian dictionary to hand, this translates into English as ‘Gold Wing’ – which also just happens to be Honda’s corporate logo, of course!

The first fruit of the Italian link for devotees of God’s own motorcycle was the 250cc Sprint, unveiled in 1960. Basically, it was an Aermacchi Ala Verde, featuring the horizontal cylinder single mounted in a spine frame.

With around 18hp at 7500rpm, it wasn’t astonishingly fast, but more power gradually became available on succeeding models. Development continued through a series of confusing designations and the later Scrambler model was claimed to deliver 25bhp at 8700rpm.

In typically Italian fashion, lots of changes were made to engines and chassis at times that vary according to which source you believe. What seems to be fairly certain is that the original long-stroke 250cc engine was converted to short-stroke (72 x 61mm) dimensions, and spawned a 293cc version using the later bore with the original stroke. Another step up came with an expansion to 74 x 80mm, giving 344cc. Although the stretching process continued, the engine was probably happiest as a 350, which was really the smallest bike a self-respecting American would consider riding.

In typically Italian fashion, lots of changes were made to engines and chassis at times that vary according to which source you believe. What seems to be fairly certain is that the original long-stroke 250cc engine was converted to short-stroke (72 x 61mm) dimensions, and spawned a 293cc version using the later bore with the original stroke. Another step up came with an expansion to 74 x 80mm, giving 344cc. Although the stretching process continued, the engine was probably happiest as a 350, which was really the smallest bike a self-respecting American would consider riding.

Out on the tracks, Aermacchis were becoming a formidable force. Legendary Norton tuner, Francis Beart, finally succumbed, discovering that 350cc of Italian pushrod single could be more than a match for a Manx. As proof, Renzo Pasolini, Kel Karruthers, Alan Barnett and others went out and won races. At the TT, a 350 clocked over 130mph, almost matching one of the new-fangled Yamahas, and in 1970 Barnett came within a whisker of a 100mph Island lap.

American Machine and Foundry

Less happily, by the late Sixties, Harley-Davidson was under siege, both in the marketplace and in business terms. In 1968, company president, William H Davidson, decided that a takeover by AMF (American Machine and Foundry) was the preferred fate, marking the beginning of a new era – and not a particularly pleasant one, it’s generally thought! Even though motorcycle sales in America were booming, with AMF in charge, Harley’s big V-twins, starved of development, declined in quality and seemed to be heading for an appointment with oblivion.

Meanwhile, the adopted Italian arm of the family was failing to come up with anything genuinely new. The Sprint finally gained an electric starter in 1973 and turned into the SS350 at about the same time as Harley took over Aermacchi completely.

All of which brings us to the bike seen here, a 1974 Harley-Davidson SS350, as imported and sold in the UK under the auspices of AMF International, whose UK base was in Old Burlington Street, London.

All of which brings us to the bike seen here, a 1974 Harley-Davidson SS350, as imported and sold in the UK under the auspices of AMF International, whose UK base was in Old Burlington Street, London.

Although Aermacchis had previously been available in Britain, only the dedicated and rich would have considered buying one of the handful that ever made it to these shores. Imports were on a very small scale. But the AMF operation was a somewhat more lavish set-up, to put it mildly, with plenty of promotional money being spent on the range of lightweights.

So, did SS350 sales take off when bikes were freely available, through a network of dealers, at a reasonable price? Nope. The average 1974 punter with £560 to spend was far more likely to want a sporty two-stroke like a Yamaha RD350 or Suzuki GT380, both on offer for slightly less. If it had to be a four-stroke, the new Honda CB360 looked tempting. Or if had to be an Italian single, how about a Ducati 450 Mk3 for a few quid more?

30th birthday

For a machine nearing its 30th birthday, this example is in astonishingly original condition: the 8350-odd miles showing on the clock seems entirely believable. Just as well, really. Even though, by a quirk of fate, the factory’s entire stock of Aermacchi single parts ended up in Britain about 20 years ago, the 350 has so many unique features that finding exact replacements would be a nightmare.

The more you look, the more you notice how different everything is, from the horizontal cylinder outwards. For instance, the chassis is an object of wonder. Although racers apparently had no problems with later versions of the trademark spine frame (early ones were a bit of a liability, though), for some strange reason the SS350 sported what is described as a full cradle, with two long tubes swooping down from the steering head and around the engine, where they mate with what appears to be the same forged members used on the previous open-plan trellis.

The more you look, the more you notice how different everything is, from the horizontal cylinder outwards. For instance, the chassis is an object of wonder. Although racers apparently had no problems with later versions of the trademark spine frame (early ones were a bit of a liability, though), for some strange reason the SS350 sported what is described as a full cradle, with two long tubes swooping down from the steering head and around the engine, where they mate with what appears to be the same forged members used on the previous open-plan trellis.

Road testers of the era cast doubt on the functionality of the extra tubes, claiming that their main purpose was to protect the vulnerable cylinder in the event of a spill. Actually, if you look at the layout up under the front of the petrol tank, it seems that without these, admittedly thin-looking tubes, the steering head would be anything but rigid.

Whatever, there’s no doubt that access to the top end of the engine was made more difficult, so you might speculate that AMF’s marketing team were really just trying to offer a frame that looked stronger. Triumph were guilty of the same deception, I think, so we mustn’t be too scathing!

Forward-jutting

It’s interesting that the forward-jutting cylinder head is still well clear of the front wheel and downtubes, simply because the engine is mounted further back than usual. Even so, the wheelbase is a compact 56in, explained by an unusually short swinging arm. With the weight already distributed further back than normal, the SS350 is topped off by a pair of high handlebars, as was the fashion in those days. Program all this into your brain and you might expect flighty steering and twitchy handling.

On my first ride, this certainly wasn’t the case, but that was because the steering bearings had suffered in storage and were all but solid. Once it had been sorted out (head bearings are probably one of the few off-the-shelf spares available), I tried again. Unfortunately, the battery had gone flat in the meantime, so instead of an instant press-button start, courtesy of the Nippon Denso electric motor living atop the crankcases, I had to resort to the only method available for most of the Aermacchi’s production run.

It’s rumoured that some 500cc thumpers can be tricky to start, but how difficult can it be to fire up a modestly tuned 344cc single? Harder than you’d think, is the answer, although the problem is more to do with an awkward, fold-away kick start mounted on the left side than engine recalcitrance.

One bruised shin later, the engine was running, gentle valve gear rustle complemented by a fairly subdued throb from the silencers. Silencers? Yes, for some reason the SS350’s exhaust pipe bifurcates soon after leaving the cylinder head, terminating in a pair of droopy looking Lanfranconis.

One bruised shin later, the engine was running, gentle valve gear rustle complemented by a fairly subdued throb from the silencers. Silencers? Yes, for some reason the SS350’s exhaust pipe bifurcates soon after leaving the cylinder head, terminating in a pair of droopy looking Lanfranconis.

Possibly the logic here was again more to do with marketing than any gain in performance, but remember, almost every manufacturer tried to fit more exhaust system than strictly necessary in those days.

The tiny plastic enrichment lever on the 30mm Dellorto carb could be knocked off quickly, and a nice solid tickover was soon available, suggesting plenty of flywheel weight compared with the modern breed of Japanese single. Once underway, the engine is immediately responsive, pulling well from the bottom half of the rev range. The transmission felt to have little backlash, as on the best British singles. In fact, if it were possible to test motorcycles blindfolded (not recommended), you might think you were riding a product of the grimy Midlands rather than one built in sunny Italy.

However, the illusion begins to fade once the engine is warm enough for some more throttle because the engine displays an unexpected revviness. While most British pushrod singles never feel happy about straying too far over 5000rpm, the Italian interpretation seems all too willing to carry on. The confusing instruments (speedo and rev counter virtually identical, and no red line marking) may be some excuse to lose track, but at the 7000rpm power peak, I called it a day. Race tuned versions of the short-stroke 250 can cope with 10,000rpm, so it’s evident that well-designed pushrod operated valvegear is no embarrassment. A high camshaft and short pushrods moving in straight lines is the secret.

The 350 is restricted more by piston speed, but still manages to push out a claimed 27hp in this application, which should be enough for a top speed nearing 100mph. In one of the few (only?) UK magazine road tests, however, they struggled to break 80. Although I wasn’t going to try for a maximum on a 27 year-old rarity belonging to someone else, given the engine’s perkiness I’d be surprised if that couldn’t be bettered.

My expectations of flighty handling turned out to have some truth in practice. The steering is definitely on the light side, although there’s not enough power or speed on tap to make anything alarming happen. I suspect that just fitting a lower, narrower set of handlebars would be an improvement, allowing the security provided by a low centre-of-gravity to shine through.

My expectations of flighty handling turned out to have some truth in practice. The steering is definitely on the light side, although there’s not enough power or speed on tap to make anything alarming happen. I suspect that just fitting a lower, narrower set of handlebars would be an improvement, allowing the security provided by a low centre-of-gravity to shine through.

Alloy seven inch drums at both ends, bearing cast-in ‘AMF Harley-Davidson’ legends, provided enough stop to match the speed and weight. The servo effect of the 2ls front takes a bit of getting used after the hydraulic discs offered by Japanese manufacturers, but it’s probably a better brake than the infamous ‘comical hub’ foisted upon owners of certain British bikes.

While we’re on the subject, as the owner of a BSA B40, I can report that the Aermacchi’s engine, despite hailing from the same era and having a similar basic specification, is really in another league. However, the two do share one inevitable fault: vibration! Although the Aermacchi lacks the brain-loosening assault of the Beezer, it certainly tingles a bit, especially through the seat. The difference is that by the time it gets to be a problem you’re using about 50 per cent more revs than on the B40.

The SS350 was listed for only two years before Harley decided to concentrate on bigger and possibly better things. In 1978 the Aermacchi plant was sold off to Cagiva. As events of the last three decades have proved, motorcyclists will only buy old-fashioned bikes if they’re big V-twins – at least if they have Harley-Davidson on the tank! ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.