Some nuggets of advice, no matter how well intentioned, are far from encouraging. Robin James is telling me how to make a quick start on his Gold Star scrambler; “You just get your weight well forward, stick it in third gear, wind the revs up and drop the clutch.” It sounds simple enough so far, but then he adds; “It’s the last bit that’s important, because you need to spin the wheel. Let the clutch out too gently and you’ll either stall the engine, or turn the machine over.”

It is true that stalling would be embarrassing, but it sounds quite an attractive option compared with laying in a field with a hot (in both senses of the word) motorcycle on top of me.

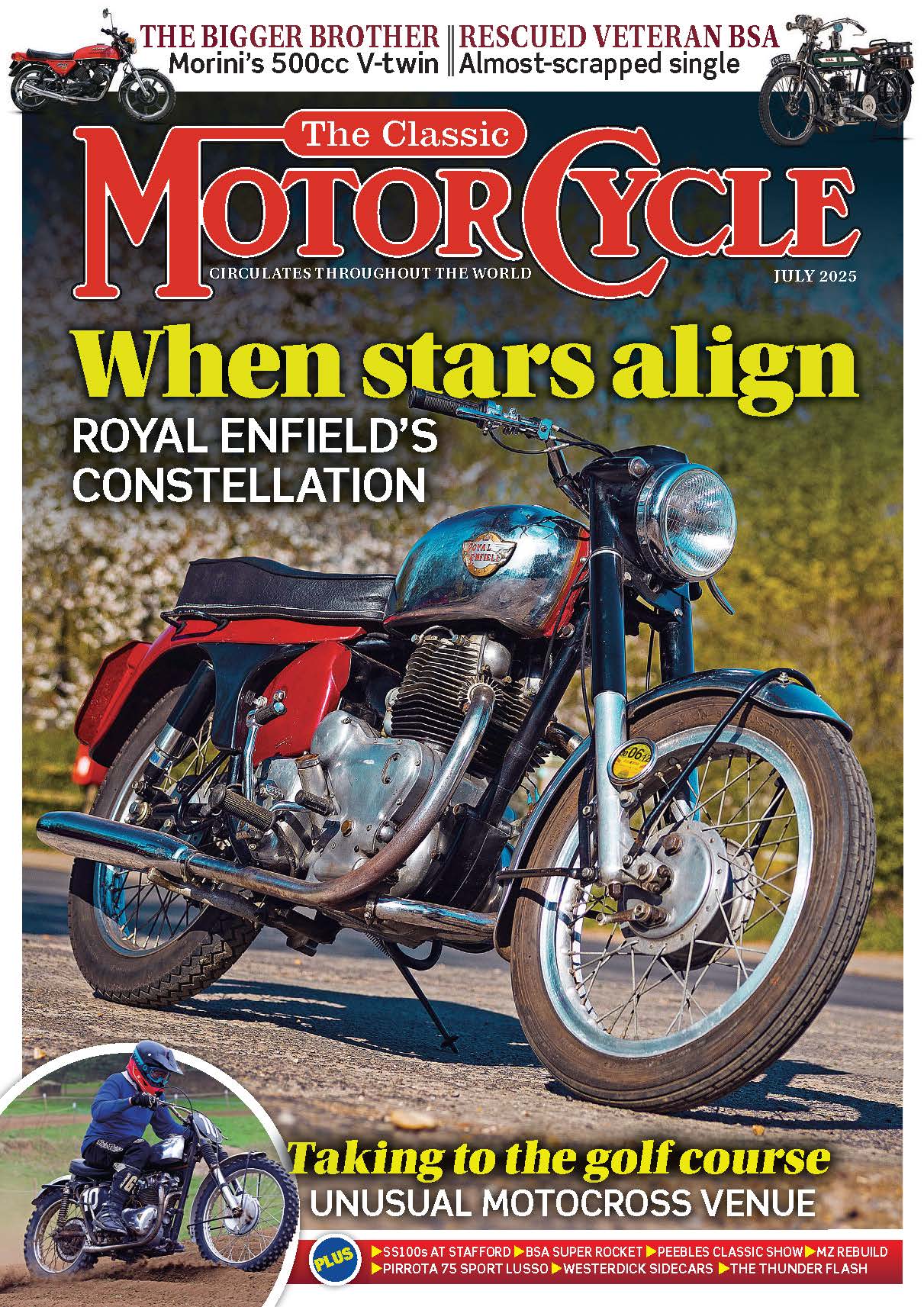

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

In the event, neither mishap occurs. The Goldie spurts off the line in a shower of dirt and gravel, and in just a second or two, I am approaching the end of my line across Robin’s practice field at what seems like a suicidal rate of knots. Am I going to spoil a quick getaway by piling into a bank? No, closing the throttle produces an immediate, and controllable, reduction in speed. Exploratory use of the brakes reveals that they could contribute more deceleration if necessary.

Owner Robin James is best known as one of the most successful and longest established restorers of classic motorcycles around. In pre-65 scrambles circles, though, he is equally highly regarded as a forceful and effective campaigner of this highly developed Goldie.

Robin has been scrambling, as he says, “…for ever.” And when you add to his experience and riding skill, his considerable technical ability and the machining facilities available to him, the result is a very potent combination.

When Robin first came across the Gold Star, he was racing an NSU engined Cotton. That sounds an odd combination, but it gave him a lot of fun until it became outclassed when; “other riders learnt how to make quarter litre BSAs go fast and still hang together.” Robin has subsequently put a BSA Starfire engine in the Cotton frame, but has been distracted from further development by his love affair with the Gold Star.

When Robin first came across the Gold Star, he was racing an NSU engined Cotton. That sounds an odd combination, but it gave him a lot of fun until it became outclassed when; “other riders learnt how to make quarter litre BSAs go fast and still hang together.” Robin has subsequently put a BSA Starfire engine in the Cotton frame, but has been distracted from further development by his love affair with the Gold Star.

In 1986, Robin was racing the Cotton/NSU in Beauval-en-Caux in Normandy, when he saw the big BSA in the hands of Sixties’ scrambles icon Johnny Draper. It had been loaned to him by Gloucester off-road specialist, and Rickman specials builder, Adrian Moss. Robin was instantly smitten and wasted no time persuading Adrian to part with the Beezer.

The Goldie came as a fairly standard device apart from its alloy tank. It had started life as a Catalina, the American-specification scrambler, and still featured the ultra-low first gear demanded by American users. This confused Robin at first, because he found its urge in the higher gears was marred by a tendency to stand still and dig holes in the lowest ratio. The ‘box now contains standard UK scrambles ratios, but the gear wheels have been lightened, not so much for the sake of overall weight reduction, as to enable quicker gear changes.

While the machine still looks fairly ordinary at a casual glance, a rolling programme of continuous use and development has improved its performance out of all recognition. When Robin talks about the changes he had made, it is most noticeable that he has an overall vision of what he is trying to achieve. He has not gone all out for maximum speed or minimal weight, rather he has concentrated on achieving considerable – but controllable – power characteristics, marrying them to a slimmed down chassis with improved handling.

The engine is the heart of any competition machine, and Robin’s development programme has turned his machine’s from a good power unit into a superb one. For starters, the DBD34GS engine has been bored and stroked from the standard 85mm x 87mm dimensions to boost the capacity to a whopping 610cc. The 90mm piston was the biggest Robin could fit into the barrel, and even then it needed a special sleeve. With racing clearances and a short skirt, the piston slaps audibly at tickover, but that is the only mechanical noise you will hear on this expertly prepared and impeccably maintained motor.

The really special aspect of the engine-stretching process is the one-off crankshaft. Machined from EN2T nickel-chrome steel, it increases the stroke by 8mm. The mainshafts are much stronger than normal too, especially on the drive side, which is one of the weaker parts of the standard design.

Speedway Jawa

The connecting rod comes from a speedway Jawa, and the gear-type oil pump has been up-rated with Velocette internals as they shift more lubricant than the BSA ones. Robin has also provided a pressurised oil feed to the rockers and the drive side main bearing; and even the cams get a direct feed through oilways in their base circles. There is a full flow oil filter naturally, and the central oil tank is insulated from shocks and vibration by rubber mounts intended for the radiator of a Ford Fiesta.

The flywheels are about 4lb heavier than standard, both because of their size, and because Robin finds they give him more traction. He recalls a recent scramble where; “…about 20 machines were bogged down in mud, but the Goldie just powered on through.” I cannot doubt the benefit, for I’m realistic enough to realise that my successful attempt at a racing start owes more to my mount than to my skill.

You might think that heavy flywheels in a large engine would produce power characteristics like those of a Panther – lots of chug but no bite. Well, look at that enormous 36mm Concentric carburettor and think again. This motor will rev as well as any normal 500cc Gold Star. What is more, it does it cleanly. There is never a hint of snatch or hesitation, so you don’t have to think about whether the motor will respond, you just open the tap and away it goes.

You might think that heavy flywheels in a large engine would produce power characteristics like those of a Panther – lots of chug but no bite. Well, look at that enormous 36mm Concentric carburettor and think again. This motor will rev as well as any normal 500cc Gold Star. What is more, it does it cleanly. There is never a hint of snatch or hesitation, so you don’t have to think about whether the motor will respond, you just open the tap and away it goes.

Robin estimates the power output at about 38hp. “It’s not the most powerful machine around but it is one of the most usable,” he claims. How right he is. Apart from anything else, Robin’s Gold Star starts reliably on the kickstart, and that could be crucial if you stall it during a race.

The engine may be fundamental to a race winner, but you still need the right chassis to put the power on the ground. Robin has left the basic frame alone to stay within the spirit of pre-65 competition, although he knows that there are some trick replicas out there which are a few pounds lighter.

He has concentrated on the detail. “Why carry excess weight in things like forged steel footrest hangers?” he reasons. Consequently, he has welded the right hand footrest straight onto the exhaust pipe, while the other is attached to the primary chaincase, as is the rear brake lever pivot. The rests are positioned 11⁄2in higher than standard to suit Robin’s slight stature and to improve ground clearance and they are of the folding type to pivot out of the way if they contact the ground.

The rear of the machine is subtly improved. After writing off two BSA swinging forks, he changed to an Ariel one, which is; “…lighter and stronger than the original.” And the sprocket, brake drum and anchor arm are all home-made in aluminium alloy which saves about 8lb.

The brake drum is actually a bit of a sore point with Robin, because he has had to make two of them. He spent 43 hours machining the first from a solid aluminium billet, and then – when he sent it off for further processing – it was lost in transit.

Lightweight alloy fasteners are used for many lightly stressed applications such as the rocker box bolts. Surprisingly, Robin includes the rear suspension units’ top mountings in his list of non-critical applications.

He has not gone overboard on weight saving though. I comment on his continued use of steel handlebars, and he tells me that falling off with the standard front end results in twisted forks and/or bent handlebars. “Neither is helpful as regards finishing a race,” he grins, “so I’ve slotted and clamped the top yoke to keep the stanchions in line, and the ‘bars are actually thicker than standard.” The handlebar levers are aluminium Magura ones, which Robin finds impossible to bend or break.

BSA A65 forks

After temporary use of BSA A65 forks, the front teles are what Robin calls ‘Nortianis’. Norton externals – some of the strongest available in the Sixties – conceal Ceriani internals giving longer movement and better damping. American Works Performance shock absorbers provide the suspension at the rear, and very effective they are. I find I can power across rough ground at speeds which I would expect to throw the machine off line, and feel in relatively full control. Robin maintains the improvement they make is worth several seconds a lap. In fact, he rates everything in these terms. He suspects that the tls alloy front brake – which is of unknown origin – is lighter than the original, but he doesn’t know by how much. He is confident that it is worth up to 20s per lap at some circuits however.

An unusual – but practical – detail on the Gold Star is the seat. Robin had it recovered by RK Leighton (0121 3590514) with untreated hide fitted inside out. The surface is tough and non-slip. “I’ve better things to do during a scramble than struggle to keep in place on the saddle,” he grins.

An unusual – but practical – detail on the Gold Star is the seat. Robin had it recovered by RK Leighton (0121 3590514) with untreated hide fitted inside out. The surface is tough and non-slip. “I’ve better things to do during a scramble than struggle to keep in place on the saddle,” he grins.

Robin can afford to let practical considerations outweigh weight saving, because he is wiry and compact. He grins as he recalls a fellow competitor telling him of the extraordinary steps he had taken to shave ounces off the weight of his scrambler. “It was all well and good,” says Robin, “except that the fellow seemed oblivious of the fact that he was carrying about 40lb of unnecessary ballast around his waist!”

Other parts made in alloy by Robin include the air filter box, and the exhaust muffler. “Fortunately the rules only say that you must have a silencer,” he tells me with a wry smile, “they don’t actually make a check to see what the noise level is.” Nobody with an ounce of appreciation for things mechanical would complain about the sound though. The Gold Star is only loud when its throttle is wide open, and then it sounds absolutely wonderful.

Despite not being fanatical about the weight-shedding process, Robin’s engineering skill has resulted in one of the lightest 500s around. He does not know how much the Goldie weighed when he got it, but it would have not been very different to the standard Catalina’s 350lb. Four years ago – after ten years of development – it scaled 315lb, and since then another 12lb have been shaved off.

This sort of improvement does not come easily. Robin works full time at his restoration business, and plays with his own machines in the evenings and at weekends. He reckons that after each event he spends 12 or 14 hours fettling the Goldie. Major developments and repairs take place in the closed season. Robin jokes that, “I spend all summer wrecking the bike, and all winter mending it.”

He is just kidding. His machine is so well developed that it can stand up to any amount of normal use. That could no doubt be said of many scramblers, but what is so remarkable about this one is its all round ability. It manages to be potent and successful, while remaining reliable and docile. In a novice’s hands, it is, as Robin describes it; “…just a big pussy cat.” But when ridden by its owner, its several competition successes show that it can be made to show its claws. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.