“I’m quite well known in Swindon for my old bikes,” says Pete Sole with typical understatement, adding for good measure, “but that’s because I can’t afford new ones!” Pete, aged 67, is a regular contributor to the classic show circuit, but it was not until two years ago that he realised his ambition to own a veteran motorcycle. A local friend had rung to ask advice about an unusual 1911 machine that had its crankcase brazed into the frame, and Pete ended up buying it out of sheer curiosity.

All the best machines come with a legend and the story that accompanied this Buckinghamshire-registered Bradbury was of it being the gift of a relieved father to his son, upon the latter’s safe return from WWI. When a subsequent crash rekindled dad’s anxiety, the machine languished, unloved but intact, in a garden shed for many years afterwards.

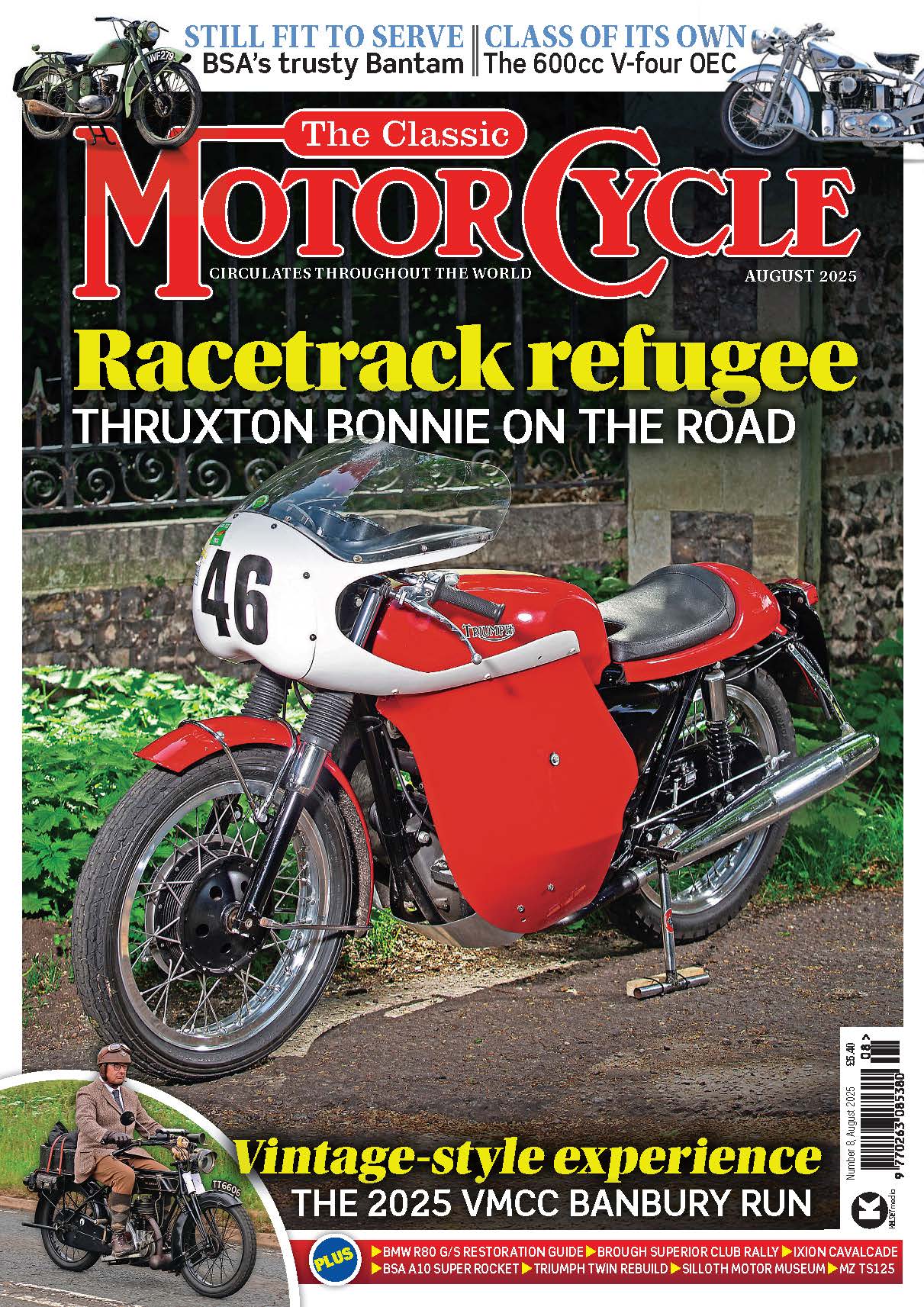

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Given that an age-related registration number was issued in June 1954, the likelihood is that it was first restored around this date, possibly in response to post-WWII pleas by the newly-founded Vintage Motor Cycle Club for the preservation of pre-1930 machines. Consequently, although some of the cycle parts had rusted badly by the time it came into Pete’s possession, underneath the black paint on its diamond frame was a liberal application of what the former British Gas employee recognised as, “Red lead – the stuff we used to paint the gas-holders with.” Indeed, the coating was thick enough in most places to rub down and retain as a base coat.

Given that an age-related registration number was issued in June 1954, the likelihood is that it was first restored around this date, possibly in response to post-WWII pleas by the newly-founded Vintage Motor Cycle Club for the preservation of pre-1930 machines. Consequently, although some of the cycle parts had rusted badly by the time it came into Pete’s possession, underneath the black paint on its diamond frame was a liberal application of what the former British Gas employee recognised as, “Red lead – the stuff we used to paint the gas-holders with.” Indeed, the coating was thick enough in most places to rub down and retain as a base coat.

There could be no questioning the match between engine case and frame, due to them being brazed together in a single unit. Bradbury and Company employed this method under Birch’s patent (registered design 380701) on all its motorcycles manufactured from 1903 onwards, having simply attached Minerva clip-on engine units to bicycles throughout the previous year. Brazed construction not only added rigidity to the single-tube frame for improved handling, but also reduced maintenance chores by dispensing with fasteners and engine mounting lugs. On the debit side, this could make the engine awkward to work on, while the use of iron instead of alloy for the crankcase negated any weight saving.

The firm had originated in 1852 as the first industrial manufacturer of sewing machines. Its Wellington Works in Oldham, Lancashire opened in 1866 and grew during the next 30 years to include a foundry, electroplating department, steel hardening section and paint shop, as well as the usual engineering and assembly functions of a modern factory, the whole site employing over a thousand workers by the beginning of the 20th century.

The 2½hp Bradbury Peerless motorcycle was uprated to 3hp for the Manchester Motor Show of November 1904, with its circular alloy cover now located on the timing side of the engine. This created a template for the 3½hp model of 1909, which was to be the mainstay of subsequent production. It was marketed from 1911 onwards in ‘Standard’ and ‘Speed’ forms, with options of a free engine hub or two-speed gearbox with belt or chain final drive. Such flexible power delivery, along with improved ground clearance and sprung front forks, led the company to claim it as ‘the finest hill climber ever made,’ able to ‘take any gradient’.

The 2½hp Bradbury Peerless motorcycle was uprated to 3hp for the Manchester Motor Show of November 1904, with its circular alloy cover now located on the timing side of the engine. This created a template for the 3½hp model of 1909, which was to be the mainstay of subsequent production. It was marketed from 1911 onwards in ‘Standard’ and ‘Speed’ forms, with options of a free engine hub or two-speed gearbox with belt or chain final drive. Such flexible power delivery, along with improved ground clearance and sprung front forks, led the company to claim it as ‘the finest hill climber ever made,’ able to ‘take any gradient’.

The NSU-type gear unit fitted to two-speed models was illustrated in cutaway form by Bradbury in its sales literature and is worthy of separate note here. Its operation was by means of a rod clamped to the nearside of the fuel tank and governed by a ratchet. Turning the handle clockwise half-a-turn engaged low gear with a 35 per cent reduction, while anticlockwise selected high gear, with a free-engine position midway between the two. Easily fitted to a tapered crankshaft, its compact design was copied by several manufacturers, despite being so complex that The Motor Cycle of 21 September 1911 counselled that ‘the amateur rider will do well to let alone’.

Drive transmitted through an epicyclical (sun-and-planets) arrangement of cogs, while an integral metal-to-metal cone clutch provided a means of slipping either gear or running on ball races in its free engine position. Requiring only regular oiling by way of maintenance, the unit’s survival in working order on Pete’s ‘Speed’ model was proof of its robust construction.

At first sight, the engine’s cylinder barrel looked in perfect condition, but its piston, despite being made from the same high-quality iron, had cracked. Markings of ‘in’ and ‘out’ did not indicate the relative positions of valves, but instead governed the insertion and removal of a tapered gudgeon pin – something a previous owner had failed to realise. There was just room, by tilting the connecting rod in the crankcase mouth, for Pete to remove the bottom-end assembly and in the course of hack-sawing the 5/8in-diameter small-end bush out of its connecting rod, he discovered that it was pinned in place.

At first sight, the engine’s cylinder barrel looked in perfect condition, but its piston, despite being made from the same high-quality iron, had cracked. Markings of ‘in’ and ‘out’ did not indicate the relative positions of valves, but instead governed the insertion and removal of a tapered gudgeon pin – something a previous owner had failed to realise. There was just room, by tilting the connecting rod in the crankcase mouth, for Pete to remove the bottom-end assembly and in the course of hack-sawing the 5/8in-diameter small-end bush out of its connecting rod, he discovered that it was pinned in place.

One of the very few documented Bradbury weak points is the thickness of its cylinder wall, so he had the barrel relined to standard bore before installing a new Honda XL500 alloy piston. The piston’s oil control ring was omitted to give total-loss lubrication precedence over compression, while a new small-end bush accommodated a thicker gudgeon pin. Both Bradbury-stamped valves and their guides were still serviceable, and the other engine internals looked good too.

The original Amac carburettor, manufactured by the Aston Motor Accessories Company of Talford Street, Birmingham, was badly rusted on the outside, so Pete applied metal filler before painting it black. Its brass-lined barrel was in better condition and only needed polishing along with the float chamber’s steel lid, secured by a bayonet fitting, which he had re-engraved with its maker’s name. Most surprisingly of all, following careful disassembly and cleaning, the Bosch magneto produced a healthy spark. Pete thinks that it slightly post-dates the bike, which may have originally carried a Simms unit. He rewired everything and made up a set of control cables, acquiring a set of brand new Bowden fold-over control levers at an autojumble, while a local pipe-bender gave assistance with the fabrication of new handlebars to the exact original pattern.

Pete spent many hours sandblasting, silver-soldering and painting the Bradbury’s combined fuel and oil tank. Although the firm experimented with different tank depths during its early years, this one is wider than standard and so may have been made or modified to special order. A cut-out section clears the spark plug and cylinder priming tap, and is deep enough to permit valve removal, though its unusual profile meant that he had to divide the offside tank transfer in two for symmetry.

Pete spent many hours sandblasting, silver-soldering and painting the Bradbury’s combined fuel and oil tank. Although the firm experimented with different tank depths during its early years, this one is wider than standard and so may have been made or modified to special order. A cut-out section clears the spark plug and cylinder priming tap, and is deep enough to permit valve removal, though its unusual profile meant that he had to divide the offside tank transfer in two for symmetry.

The acetylene lighting kit was assembled from spare parts and is approximately correct for the period, the rear Lucas lamp having a burner that slides in from below. Pete located a period leather toolbox by the rear mudguard for neatness, rather than behind the carrier as was standard practice. The gap it fills would have given clearance to pedal cranks on models so equipped, both mudguards mounting their stays to the wheel spindles.

Other personalised touches include a stainless steel collar on the centre section of the remanufactured main stand, to reduce wear from its mounting clip behind the rear mudguard. Pete also added the spring from a set of pruning shears to assist the return of the valve lifter cable, and fabricated the clips holding the acetylene lighting pipe against the frame from a BSA Bantam kick-start spring.

The entire restoration project took less than nine months and in its first year of selective public outings, collected the Champion of Champions award at Malvern and Best in Show at Stafford. It is only the physical demands of an aggressive medical treatment programme that keep Pete from curing the final impediment to full rideability. “I could have that clutch off the bike in four minutes. I’ve even made a special tool to do it,” he says, clearly frustrated. “The clutch housing contains a three-winding spring that I replaced with a five-winding valve spring and I reckon that this is becoming coil-bound on compression, which prevents me from fully disengaging the drive.”

The entire restoration project took less than nine months and in its first year of selective public outings, collected the Champion of Champions award at Malvern and Best in Show at Stafford. It is only the physical demands of an aggressive medical treatment programme that keep Pete from curing the final impediment to full rideability. “I could have that clutch off the bike in four minutes. I’ve even made a special tool to do it,” he says, clearly frustrated. “The clutch housing contains a three-winding spring that I replaced with a five-winding valve spring and I reckon that this is becoming coil-bound on compression, which prevents me from fully disengaging the drive.”

Contemporary reports give the impression of a big-flywheel slogger with a flexible transmission to match. Smoother than some rivals and with less vibration due to its integral engine, Bradbury machines regularly made headlines with record end-to-end runs or epic sidecar hauls up steep inclines. The low ratio in this geared-drive model would prove useful for push-starting and would also help to retard momentum during a descent. Pete describes the riding experience as, “Pretty hands-on – juggling levers, plungers and handles, besides keeping an ear on the engine note, an eye on the amount of exhaust smoke and wondering whether it will stop in time.”

Sitting on the tall but well-sprung period saddle, I test the limited movement of the front suspension. Bradbury manufactured linkages for standard Druid fork blades in-house under licence. The side-springs extended under load and could be specified for the weight of a rider, the whole assembly adding an extra £1 to the retail price over a rigid front end, with Dunlop studded tyres costing a further £1 on top.

These low-revving engines made practical sidecar tugs and were sometimes adapted for use in heavyweight lawnmowers, which also employed a lever throttle. The throttle pivot is shared with a choke control on the right handlebar, an inverted hand lever operating a flimsy-looking stirrup front brake. The inverted lever on the left handlebar is the exhaust valve lifter, while its near neighbour controls the ignition. A right-foot pedal operates the belt rim brake on the rear wheel.

Pete says that he has learned over the years that an ND M-17 spark plug runs at an ideal temperature for burning excess oil in total-loss engines, and the Bradbury’s forward-mounted canister silencer has a swivelling plate to mask its two larger outlets for quiet running. Consequently, its exhaust is neither excessively smoky nor loud, although there is always a certain reassurance in seeing some visible emanations from a gravity-fed lubrication system, quite apart from enjoying the distinctive aroma of Castrol ‘R’.

Pete says that he has learned over the years that an ND M-17 spark plug runs at an ideal temperature for burning excess oil in total-loss engines, and the Bradbury’s forward-mounted canister silencer has a swivelling plate to mask its two larger outlets for quiet running. Consequently, its exhaust is neither excessively smoky nor loud, although there is always a certain reassurance in seeing some visible emanations from a gravity-fed lubrication system, quite apart from enjoying the distinctive aroma of Castrol ‘R’.

The 3½hp single-cylinder model defined Bradbury’s reputation for robust construction and useful power within manageable dimensions, a combination that brought the company sporting success in other engine formats too. Its 554cc motor was uprated to 4hp with chain drive, kick-starter and a hand-operated clutch for 1914. Although excluded from War Department trials, the basic design endured to the spring of 1924, when all Bradbury production ceased. Such was the company’s status as a motorcycle manufacturer by this time that its demise was felt throughout the industry.

Pete says he is delighted to have worked on an authentic example of a machine built almost 100 years ago, particularly one that seems to embody all that was excellent in veteran design. He adds, “I am an amateur restorer and to my mind, if something looks right then it is right. The standard of this bike is something I’m quite pleased with and I hope that seeing it looking like new will encourage people to learn about its history.” ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.