Hampshire-man John Craven is a self-confessed AJS/Matchless nut. It could hardly be otherwise when he was born into a similarly obsessed family, and actually travelled on an AJS before he was even born; his expectant mother being whisked to the maternity hospital on the back of his dad’s Silver Streak! That extravagantly chromed model had replaced a ‘cammy’ AJS on which Mr Craven had raced at Brooklands in 1939, and it was then carefully stored away to prevent any chance of it being donated to an unappreciative despatch rider during the war. After John’s arrival the Silver Streak was replaced by an AJS Model 18 shackled to a Noxal sidecar, and in it he was taken part-way to the TT when only 18 months old!

Predictably, John soon caught the AMC bug, and, as a youngster he grass-tracked the Big Port AJS that his dad had also preserved from before the war. Mr Craven Senior remained so keen on AMC singles that in 1952 he took the family to Edinburgh in a combination powered by his second post-WWII Model 18, “the 1948 version with bigger brakes,” says John with the assurance of one who knows his chosen marque inside out. And they all had a month-long stay there while Mr Craven waited to learn if he was going to be called up from the reserve list and sent to Korea.

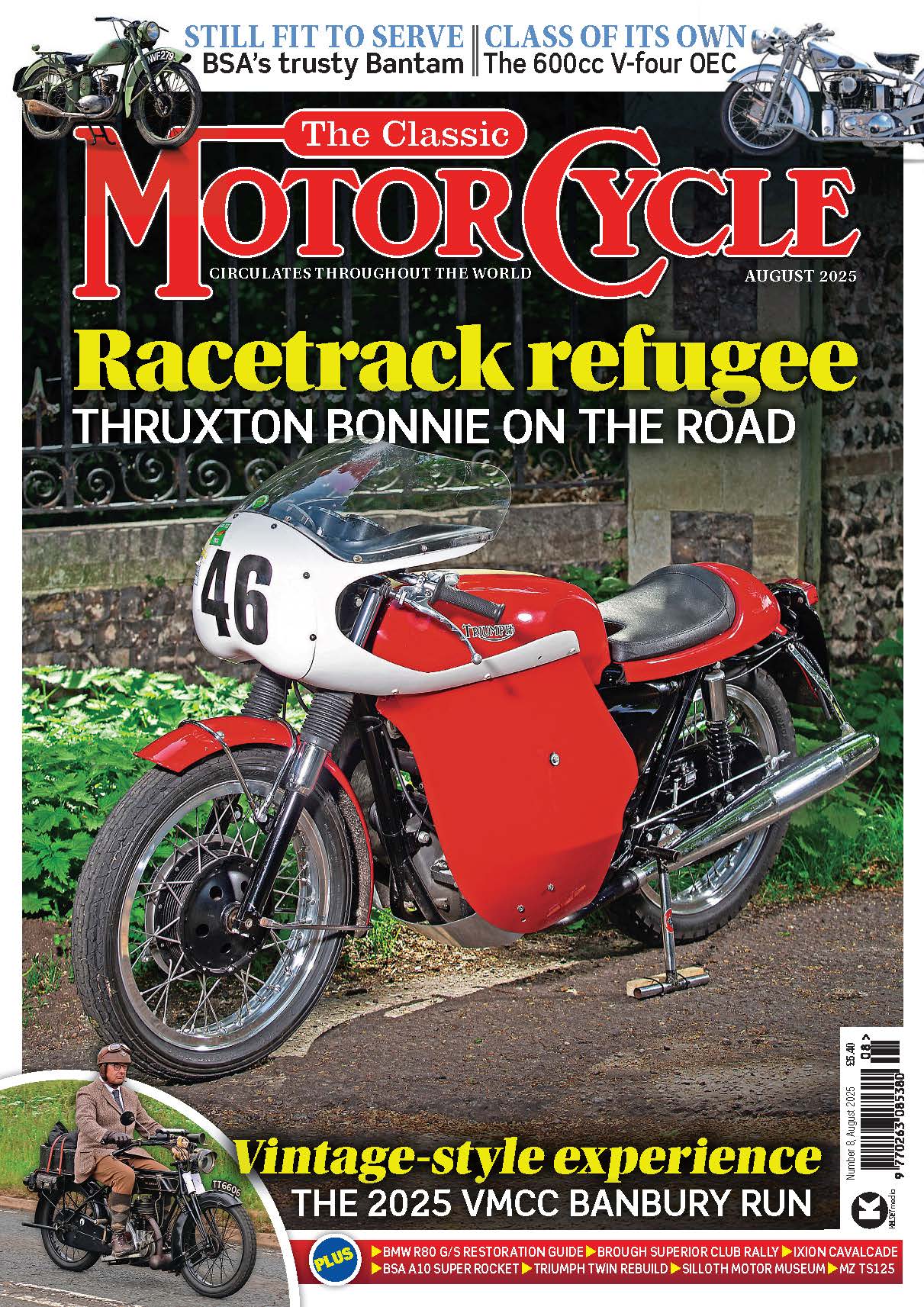

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Fortunately, he escaped that particular engagement, and returned to his job as Works Manager in a car garage. Despite his job, he was obviously no lover of four-wheeled vehicles, and a couple of years later he upgraded to a Triumph Thunderbird-powered outfit (presumably with reluctance, and only because AMC didn’t make a 650cc twin at the time!) to transport his expanding family. Still finding insufficient space on board when touring, he then added a caravan and John remembers the ambitious ensemble venturing as far as Cornwall on holiday.

Fortunately, he escaped that particular engagement, and returned to his job as Works Manager in a car garage. Despite his job, he was obviously no lover of four-wheeled vehicles, and a couple of years later he upgraded to a Triumph Thunderbird-powered outfit (presumably with reluctance, and only because AMC didn’t make a 650cc twin at the time!) to transport his expanding family. Still finding insufficient space on board when touring, he then added a caravan and John remembers the ambitious ensemble venturing as far as Cornwall on holiday.

Coincidentally, the Model 18 AJS featured here was made in the year of the trip to Scotland, and I’m sure Mr Craven was delighted to see it enter the family stable. John, himself, describes the bike as ‘a faithful old friend’, and with very good reason. He bought it for a measly tenner, way back in the early-1960s, and it (or ‘she’ as he affectionately calls his big single) has been a reliable workhorse ever since. So reliable and ready to work, in fact, that in 1969 John’s parents actually borrowed it, with a sidecar attached, in order to tour the continent.

Now, motorcycles that have had long-term ownership tend to fall into two categories. They are either used and abused, and held together with wire and sticky tape, or they are cosseted and polished, and only taken out on sunny summer days. Well, neither stereotype applies to John Craven’s AJS. This is a motorbike whose immaculate appearance belies the fact that it stems from a major rebuild taking place a quarter of a century ago, or that its odometer has been right round the clock a couple of times.

Tender loving care and sensible riding are the keys, of course, and John is not afraid to put his beliefs to the test. Just a couple of days before I went to see him, he’d covered a thousand miles in the course of a weekend on another of his AMC singles, riding via Wales to the Lake District, where he’d taken part in the VMCC’s Hesket event. “She never missed a beat, either,” he says in the tone of one who would be shocked if there had been any hiccups. He’s also ridden the featured AJS in other long-distance events like the Irish Rally – a notorious machine wrecker – and has never been sidelined.

Naturally, a workload like that means that John has to keep on top of the maintenance schedule. And, luckily, his obvious mechanical sympathy is matched by mechanical skill. He served a craft apprenticeship in Portsmouth Naval Dockyards, and followed an engineering career, so he can do whatever is required to keep his bikes in fine fettle. “The big ends usually last about 40,000 miles before they begin to get noisy, and then it’s fairly simple to put in new rollers or crankpins,” he calmly says, exhibiting both a confidence in his own abilities, and an acceptance of the need for occasional work on classics that cover serious mileages.

Naturally, a workload like that means that John has to keep on top of the maintenance schedule. And, luckily, his obvious mechanical sympathy is matched by mechanical skill. He served a craft apprenticeship in Portsmouth Naval Dockyards, and followed an engineering career, so he can do whatever is required to keep his bikes in fine fettle. “The big ends usually last about 40,000 miles before they begin to get noisy, and then it’s fairly simple to put in new rollers or crankpins,” he calmly says, exhibiting both a confidence in his own abilities, and an acceptance of the need for occasional work on classics that cover serious mileages.

The AJS’s owner’s skill and care has resulted in an appearance that matches its mechanical condition. Unless I’d been told, I’d never have guessed that the lustrous black finish on parts like the mudguards and oil tank was the result of brush-painting with enamel. “I used ordinary Japlac,” says John, subsequently admitting that a deal of patience was required to apply about four coats of paint with intermediate rubbing down using fine wet-and-dry paper.

"When I first got the Model 18 it was in a bit of a state, and I contacted AJS, who offered to re-paint the tank for a fiver or the whole bike for twice as much. I had the tank done, and it was to AMC’s usual high standard…"

“In the old days, the factories were marvellous,” he continues, contradicting the usual opinion of British industry. “When I first got the Model 18 it was in a bit of a state, and I contacted AJS, who offered to re-paint the tank for a fiver or the whole bike for twice as much. I had the tank done, and it was to AMC’s usual high standard, but it eventually fell against a wall while it was removed for a maintenance session, and I had to have it repainted.”

I’m not sure how best to describe John’s work on his AJS. It’s neither a conventional full-scale restoration – although it has been completely taken down and rebuilt at least twice – but neither has he only done work as and when it was required. I suppose the nearest I’ll get is to call it a rolling restoration with jobs being undertaken before they become essential, rather than after a disaster has occurred.

I’m not sure how best to describe John’s work on his AJS. It’s neither a conventional full-scale restoration – although it has been completely taken down and rebuilt at least twice – but neither has he only done work as and when it was required. I suppose the nearest I’ll get is to call it a rolling restoration with jobs being undertaken before they become essential, rather than after a disaster has occurred.

Whatever, the result is absolutely superb, and a casual observer would be hard pressed to guess the AJS’s age. Apart from the ‘as-new’ appearance, that’s due to this being a model that could be used as a definition of the phrase ‘traditional British single’, as it was never subjected to abrupt changes in style. Instead, it evolved gently from its introduction in 1936 until its demise – along with a large chunk of the British industry it epitomised – 30 years later.

The first 500cc Model 18 actually appeared slightly earlier, but that was effectively a re-labelling of an existing motorcycle with the then-fashionable sloping engine. The true genesis of the test machine was the 1935 350cc single, which, for the first time, showed the extent of the badge engineering that would eventually result in virtually identical AJS and Matchless ranges.

Matchless had taken over their struggling Wolverhampton rivals in 1931, and soon moved AJS production to Plumstead, Woolwich in south-east London. Four years later, one of the combine’s most successful models was introduced as the 350cc Matchless G3 – which would be developed into the military machine beloved by thousands of servicemen – and alongside it came the similar Model 16 AJS. The most obvious difference between the versions being that the AJS had a forward-mounted magneto, while that on the Matchless was tucked behind the cylinder. These machines had upright engines with quite a long stroke (much longer than their predecessors in fact) and so it was an obvious step for the cash-conscious Associated Motorcycle Company – as the conglomeration was known from 1937 – to create a big-bore version with a capacity of 500cc.

Enter the archetypical Model 18 AJS. Naturally, it had a rigid frame, single saddle and girder forks, but after the war AMC singles were given the telescopic forks pioneered on the military G3L. And in 1949 – much sooner than the opposition with the honourable exception of Royal Enfield – the Model 18S variant appeared with modern swinging arm rear suspension. Initially AMC used the skinny suspension units nicknamed Candlesticks, but their dimensions limited the volume of damping fluid they could carry, and in 1951 they were superseded by the splendidly sturdy-looking ‘Jampots’ you see on the test bike.

Enter the archetypical Model 18 AJS. Naturally, it had a rigid frame, single saddle and girder forks, but after the war AMC singles were given the telescopic forks pioneered on the military G3L. And in 1949 – much sooner than the opposition with the honourable exception of Royal Enfield – the Model 18S variant appeared with modern swinging arm rear suspension. Initially AMC used the skinny suspension units nicknamed Candlesticks, but their dimensions limited the volume of damping fluid they could carry, and in 1951 they were superseded by the splendidly sturdy-looking ‘Jampots’ you see on the test bike.

I get the impression that they are stronger on comfort than on control, though, despite the fact that John has rebuilt the units (dismantlability is one of their virtues) and I guess they are as effective as they ever were. A good pair of Girlings – or modern substitutes – would doubtless improve the handling, but that’s as irrelevant as saying that Norton Roadholders would be better than the AMC Teledraulic forks. Yes, I know that AJS/Matchless did actually switch to Girlings in 1957, and fitted Norton forks in 1964, but by then the frame and engine had evolved, too, so it’s pointless comparing early and late examples of the spring frame Model 18.

What is relevant is that the soft handling is perfectly in keeping with the performance of the docile engine. You can forget any preconception that a 500cc single is going to be a handful to start and ride, because this one is just a big softie. After easing it over compression, a single gentle prod invariably has it chuffing away. John warns me that the clutch’s take-up is a bit sudden, and that’s true – although it’s the sort of characteristic you get used to in a very few miles – but the torquey motor just drops a few revs as it takes up the load, and away you go with no danger of stalling. The problem (if that’s not too strong a word to use) is probably due to worn slots on the clutch basket, because once my attention has been alerted I can just hear a tinkling noise when the clutch is withdrawn.

What is relevant is that the soft handling is perfectly in keeping with the performance of the docile engine. You can forget any preconception that a 500cc single is going to be a handful to start and ride, because this one is just a big softie. After easing it over compression, a single gentle prod invariably has it chuffing away. John warns me that the clutch’s take-up is a bit sudden, and that’s true – although it’s the sort of characteristic you get used to in a very few miles – but the torquey motor just drops a few revs as it takes up the load, and away you go with no danger of stalling. The problem (if that’s not too strong a word to use) is probably due to worn slots on the clutch basket, because once my attention has been alerted I can just hear a tinkling noise when the clutch is withdrawn.

The testers of old had the real difficulty of reviewing new motorcycles without offending their manufacturers. Even mild criticism had severe repercussions, and it’s well known that for years no AJS or Matchless bikes were made available to the press because AMC’s management had taken exception to a comment made in print. I have an entirely different problem, today, as – apart from not wishing to offend John – testing a bike as well-sorted as his AJS leaves me with little to criticise.

In fact, he forestalls me by pointing out what he sees as discrepancies and shortcomings that, like the clutch’s behaviour, I would probably not have thought worthy of comment. For instance, he reckons that there is a bit of a whine in third gear, saying, “as usual with Burman boxes.” To hear it, though, you’d have to be more familiar with the AJS than I’m likely to become in an afternoon’s riding. And there’s no excessive engine racket to drown it out, either, AMC singles are inherently quiet-running, and it’s no surprise to find that this one is better than average in that respect.

John also points out a couple of minor deviations he’s made from the Model 18S’s standard specification. “The separate float chamber carburettor was getting quite worn,” he says, “but there didn’t seem much point in having it refurbished when an improved version was available off the shelf for about the same money.” AMC themselves made the same change as soon as the Amal Monobloc became available in the mid-1950s, so no great liberties have been taken there.

John also points out a couple of minor deviations he’s made from the Model 18S’s standard specification. “The separate float chamber carburettor was getting quite worn,” he says, “but there didn’t seem much point in having it refurbished when an improved version was available off the shelf for about the same money.” AMC themselves made the same change as soon as the Amal Monobloc became available in the mid-1950s, so no great liberties have been taken there.

Real anoraks will notice that John’s AJS doesn’t have the skinny barrel silencer fitted in the early 1950s. Well, he has a barely used pattern item in that style on the shelf, but when he fitted it he didn’t like the flat exhaust note, so he switched to the more modern shape that came in about the same time as Monobloc carburettors. What else? Not much really. John has switched to stainless steel for the seal holders on the front forks, and the lower shrouds on the rear suspension units, but otherwise everything is pretty much as AJS intended.

If you set out to buy an AJS or Matchless single, you’ll find that the 350cc versions seriously predominate, and conventional wisdom has it that those smaller models are sweeter to ride, and riding solo on a level road that may well be the case. At any other time, however, the half-litre jobs’ reserve of power makes them more desirable, and I dare say that their relative scarcity actually results from buyers who couldn’t, or wouldn’t, fork out the extra £18 that AMC cynically demanded for a motorcycle costing no more to make. That scarcity in turn results in the bigger bikes commanding higher prices today, but if you are in the market for an undemanding and ‘faithful old friend’, John Craven’s experience indicates that you’ll never regret the extra investment. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.