You can just imagine the ribald comments a present-day rider would get if he or she rode a motorcycle made by a firm called King Dick. And that’s not just me being unduly sensitive or prurient, because when I did a bit of Internet research on the firm I found some links that were downright bizarre, and nothing whatever to do with motorcycling! But things were obviously different in Victorian days, as that’s when the words were deliberately added to the firm’s title to symbolise ‘British tenacity and strength of character’. Well, that’s lost on us now, but a British Bulldog logo was introduced at the same time, and at least the symbolism of that is still unmistakable.

The firm had previously been named the Abingdon Engineering Company, and it had been founded in 1856 to make mechanical items like tools, chains and gearboxes. The Abingdon Works were located in the heartland of the British automotive industry at Tyseley in Birmingham (subsequently better known as the home of Excelsior motorcycles), and unless a reader is better informed than me, or the Internet, we can only speculate on the origins of the original company name. Perhaps it was a family moniker, or there was some connection with the Oxfordshire town of Abingdon, who knows? The firm is still in existence, and – although the first part of the name and the motoring connection have largely been forgotten – King Dick spanners and hand tools are as well respected as ever, and still bear the distinctive Bulldog logo.

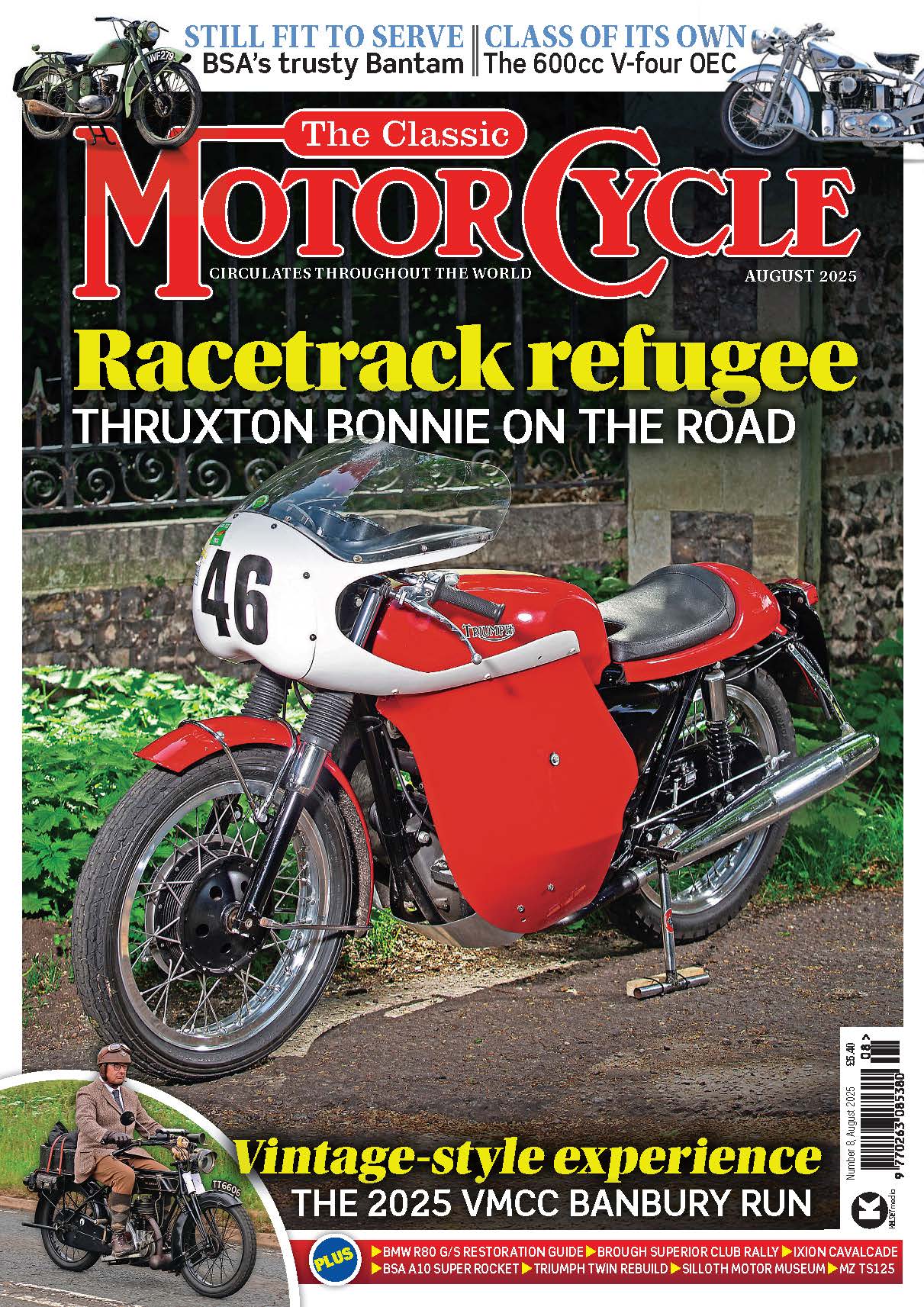

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Anyway, around the beginning of the last century, the newly renamed Abingdon King Dick Company found itself having close connections to the fledgling bicycle and automotive industries, and decided to get further involved. This initially meant developing established lines, and by 1903 the firm had developed an innovative axle for the rear wheel-drive tricycles that were enjoying a brief period of popularity. It consisted of a pulley driving a differential, but its most striking feature was that the pulley was plain sided, and could be slowed by friction pads. In essence it was probably the world’s first disc brake, and that alone should ensure the firm some sort of immortality.

Anyway, around the beginning of the last century, the newly renamed Abingdon King Dick Company found itself having close connections to the fledgling bicycle and automotive industries, and decided to get further involved. This initially meant developing established lines, and by 1903 the firm had developed an innovative axle for the rear wheel-drive tricycles that were enjoying a brief period of popularity. It consisted of a pulley driving a differential, but its most striking feature was that the pulley was plain sided, and could be slowed by friction pads. In essence it was probably the world’s first disc brake, and that alone should ensure the firm some sort of immortality.

Abingdon King Dick motorcycles were quickly on the scene, too, and initially used a variety of proprietary engines, including MMC, Minerva and Kerry. Not content with that, the business started developing its own engines, and within a couple of years was experimenting with a four-stroke motor having a mechanically operated overhead inlet valve. Newcomers to pioneer motorcycling might not realise it, but the valve layout alone was sufficient to mark the company out. Everybody knew that ohv engines were potentially more efficient, but only the most forward-looking of manufacturers risked trying to develop them. Metallurgy had not developed sufficiently for valves and springs to reliably withstand the heat generated by an engine, and while broken valve gear in a side-valve engine merely stopped it working, it could result in mechanical havoc if a valve dropped onto the piston of an overhead valve motor.

Abingdon’s experiments evidently came to nothing in the short term, and its early production engines were fairly conventional. They were well respected, though, and by 1915 Sunbeam chose to specify them in place of the JAP units used previously in their big V-twin. By the 1920s, Abingdon King Dick engines ranged from a 350cc single up to an 800cc twin, and the firm’s own motorcycles mostly used gearboxes manufactured in-house too. Up to this point, the motorcycles seem to have had tank transfers showing Abingdon in a central logo, with the words ‘King’ and ‘Dick’ on either side, but in 1925/6 there was a sea change. The clumsy name was suddenly contracted to the initials AKD, and that’s how the machines were badged until production ended in 1932/3.

Abingdon’s experiments evidently came to nothing in the short term, and its early production engines were fairly conventional. They were well respected, though, and by 1915 Sunbeam chose to specify them in place of the JAP units used previously in their big V-twin. By the 1920s, Abingdon King Dick engines ranged from a 350cc single up to an 800cc twin, and the firm’s own motorcycles mostly used gearboxes manufactured in-house too. Up to this point, the motorcycles seem to have had tank transfers showing Abingdon in a central logo, with the words ‘King’ and ‘Dick’ on either side, but in 1925/6 there was a sea change. The clumsy name was suddenly contracted to the initials AKD, and that’s how the machines were badged until production ended in 1932/3.

Perhaps the Tyseley firm foresaw difficult times ahead, and decided to streamline both their title and their approach. Gone were the heavyweights, and, indeed, it appears that production might have stopped altogether for a while, as James Sheldon’s respected reference book Veteran and Vintage Motorcycles teasingly says that in 1928 AKD ‘came back’ as manufacturers. What is beyond doubt is that from then onwards, the mainstay of production was a very neat little four-stroke, just like the one you see on these pages.

But we’re not over with the questions yet. AKD claimed that the engine was its own, and contemporary magazine articles didn’t disagree. Left to my own devices I’d have trustingly gone along with that, but Sammy Miller – who owns the diminutive bike, and has more experience than most of us – thinks differently. “No,” he says, “it’s a Swiss Moser engine, and nothing like the AKD jobs.” Looking at the motorcycle itself, and the reference material, I have to say that he has a point. St Aubin-based Moser is a long forgotten marque, but – like AKD themselves – it made both engines and complete motorcycles, and was in business over a similar period, from 1905 to 1935.

In the 1920s Moser was very successful in continental racing with 125cc and 175cc versions of its little four-stroke, the best result being a one-two in the Swiss Grand Prix. The memorably named Omobono Tenni was third on another make of motorcycle on that occasion, but he subsequently became Moser’s best-known star. What’s all this got to do with AKD? Well absolutely nothing if you take AKD’s literature at face value. But the Moser engine was very, very, distinctive, and it was exactly like the supposed AKD engine in the test machine!

In the 1920s Moser was very successful in continental racing with 125cc and 175cc versions of its little four-stroke, the best result being a one-two in the Swiss Grand Prix. The memorably named Omobono Tenni was third on another make of motorcycle on that occasion, but he subsequently became Moser’s best-known star. What’s all this got to do with AKD? Well absolutely nothing if you take AKD’s literature at face value. But the Moser engine was very, very, distinctive, and it was exactly like the supposed AKD engine in the test machine!

Looking at AKD’s literature with a more jaundiced eye, I notice that it states; ‘For many years we have specialised in the design and manufacture of engines for motor cycles…and…Every AKD engine is manufactured throughout in the famous Abingdon works’. Nobody disputes that AKD designed engines, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that they designed this one, does it? And while they might have put the engine together in their factory, they could still have started with a design from Moser or a kit of Moser parts, couldn’t they? Perhaps significantly, the only British Patent quoted by AKD refers to the rather naff-looking, quickly detachable clips that secure the engine to the frame.

In a sea of two-stroke utility motorcycles and slogging side-valvers, the little ohv AKD would certainly have looked a bit foreign. Motor Cycle magazine tested one in 1929, and observed that; ‘In this country the design of ultra lightweight machines has been very largely confined to the two-stroke, and motor cyclists have become accustomed to regard the baby mount as something quite apart from the sporting single-cylindered machine…In one or two cases, however, the popular trend has not been followed, certain manufacturers preferring to extend the four-stroke to the smallest class…The super-sports 174cc AKD is a machine which possesses an unusual degree of individuality’.

In a sea of two-stroke utility motorcycles and slogging side-valvers, the little ohv AKD would certainly have looked a bit foreign. Motor Cycle magazine tested one in 1929, and observed that; ‘In this country the design of ultra lightweight machines has been very largely confined to the two-stroke, and motor cyclists have become accustomed to regard the baby mount as something quite apart from the sporting single-cylindered machine…In one or two cases, however, the popular trend has not been followed, certain manufacturers preferring to extend the four-stroke to the smallest class…The super-sports 174cc AKD is a machine which possesses an unusual degree of individuality’.

Once you start reading between the lines, the words ‘in this country’ and ‘unusual’ seem to substantiate Sammy’s theory that AKD – with the support of the press – was covering up the use of an engine that wasn’t home built. But if so, they achieved little except salvaging a little pride, because the Moser/AKD engine was certainly nothing to be ashamed of. In fact, it was just about as good as lightweights got in vintage days, with AKD’s sales literature claiming that; ‘A speed of 60/65 miles per hour is obtainable if well cared for.’ That would mean that the 175cc AKD could have given away 25cc and still been a match for something like a 1960s Tiger Cub, so perhaps there was a little creative literature there, but Moser’s competition results unarguably showed that the engine had potential.

And so it should have had, because it cleverly combined advanced technical features with good engineering practice and mechanical simplicity. In fact, it’s so simple that its design is obvious from the outside. A single camshaft running across the back of the engine case is rotated by the half time pinion, which also drives the magneto. The parallel pushrods are situated at the back of the cylinder, and operate rockers that run forwards to operate two parallel valves set vertically in the cylinder head. Strangely, the firm’s brochure and the Motor Cycle article refer to ‘inclined valves’, when the same literature – and the bike itself – clearly shows that they are set vertically. Another attempt to blur the engine’s origins, perhaps?

And so it should have had, because it cleverly combined advanced technical features with good engineering practice and mechanical simplicity. In fact, it’s so simple that its design is obvious from the outside. A single camshaft running across the back of the engine case is rotated by the half time pinion, which also drives the magneto. The parallel pushrods are situated at the back of the cylinder, and operate rockers that run forwards to operate two parallel valves set vertically in the cylinder head. Strangely, the firm’s brochure and the Motor Cycle article refer to ‘inclined valves’, when the same literature – and the bike itself – clearly shows that they are set vertically. Another attempt to blur the engine’s origins, perhaps?

Still, what a good design it was. The high camshaft and compact valve gear would discourage valve float at any revs that could be sustained by the rest of the engine, and the nearly square engine dimensions and aluminium piston promised that plentiful revs would be available. The closely spaced parallel valves allowed the combustion chamber to be efficiently shaped, and if their exposure looks a bit primitive, we have to remember that cooling was more important than lubrication in the 1920s. The good news continued inside the engine with a roller bearing big end, and the crankshaft, camshaft, and valve rockers all ran on ball bearings.

The engine’s design meant that the spark plug was situated at the front where it benefited from maximum exposure to cooling air, but this resulted in one of the few obvious design compromises. The late 1920s was a period when any restriction to the exhaust was felt to restrict power output (present-day teenagers with raucous twist and go scooters obviously think the same!) and while the cooking version of the 175cc AKD had a single exhaust, the Super-Sports Model 78 featured here had twin pipes. However, its spark plug position – and the offset of the exhaust valve to the right – mean that exhaust gases had to negotiate an awkward internal port to reach the left hand pipe. The result is that the twin port design looks better, but is heavier and probably less efficient.

The engine’s design meant that the spark plug was situated at the front where it benefited from maximum exposure to cooling air, but this resulted in one of the few obvious design compromises. The late 1920s was a period when any restriction to the exhaust was felt to restrict power output (present-day teenagers with raucous twist and go scooters obviously think the same!) and while the cooking version of the 175cc AKD had a single exhaust, the Super-Sports Model 78 featured here had twin pipes. However, its spark plug position – and the offset of the exhaust valve to the right – mean that exhaust gases had to negotiate an awkward internal port to reach the left hand pipe. The result is that the twin port design looks better, but is heavier and probably less efficient.

The AKD still goes well, though. It’s been in Sammy Miller’s Museums for considerably more than a decade, and that’s Museums in the plural, because its arrival pre-dated the move to the present site at Bashley Cross Roads, New Milton Hants BH25 5SZ, tel 01425 620777. Before acquisition it had already been restored in an amateur way, and Sammy has never used it or done anything to it. Dragging it out a few weeks ago, his chief spannerman – Bob Stanley – cleaned the plug, put a bit of petrol in the tank, gave it a kick, and it started!

Since then, all that’s been done before I’m invited to give it a spin is the fitting of a new exhaust. Now I’m no stranger to vintage lightweights, and I once rode a 196cc James from John O’Groats to Lands End, but I’d have rather done it on the AKD. It starts up readily, without any particular technique, and ticks over with the busy sort of noise you’d expect from an engine with exposed valve gear, and which is well used but not knackered.

The gear lever is a bit reluctant to do its job, and Bob suggests that old grease may have solidified around the detent spring. I suspect he’s right, as things get easier as my ride progresses, and the stiff action isn’t all bad news, anyway. The long lever on the lightweight Albion gearbox pivots on a very narrow bearing area, so the absence of the expected wobbly feel indicates that the AKD hasn’t covered too many miles.

The frame is pretty good, too. AKD took a leaf out of Cotton and Francis Barnett’s books, and used straight tubes wherever possible – notably from the steering head to the rear axle. The engine cradle is a sturdy casting (just as well with the lack of support from those patented engine clamps!), but otherwise the frame is largely bolted-up, and repairs easy.

The frame is pretty good, too. AKD took a leaf out of Cotton and Francis Barnett’s books, and used straight tubes wherever possible – notably from the steering head to the rear axle. The engine cradle is a sturdy casting (just as well with the lack of support from those patented engine clamps!), but otherwise the frame is largely bolted-up, and repairs easy.

The brakes are small, but reasonably effective with such a lightweight bike, and the seating position is not as cramped as I’d expected. That’s largely thanks to the bicycle-type mounting stem, where raising the saddle from the ground-hugging position favoured in the late-1920s also moves it slightly backwards.

There aren’t many sub-200cc vintage bikes I’d choose to use on longer Vintage club events, but the four-stroke AKD is an exception to the rule, and I’d be happy to tackle the Banbury Run on it – Sunrising Hill and all! Motor Cycle’s tester wrote that; ‘The super-sports 174cc AKD is a machine which possesses an unusual degree of individuality. It is small, but only as regards its engine capacity, and its performance is such as to render entirely absent any impression that one is astride a toy.’

I’d say he got it exactly right. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.