Nassetti 1951-57 Italy

Accessory maker Ettore Nassetti, who during the early to mid-1950s built friction drive cycle attachments, which were also supplied mounted in suitable frames. He went on to design and build 49cc mopeds including the Sery and Dilly, using both tubular and pressed steel frames.

Neander 1924-29 Germany

Relying on a range of 122cc two-stroke to 1000cc ohv V-twin engines from Villiers, Kuchen, MAG and JAP, Ernst Neumann-Neander built distinctive but unorthodox machines, with cadmium coated Duralumin frames. Ernst also tried leaf spring front fork, fuel tanks integral with frames and bucket seats instead of saddles.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Neumann-Neander licensed selected rolling chassis designs to Opel, who fitted their own engines and also built one-off machines to customer’s specification, using engines of their choice.

Negas (Nagas) & Ray 1925-28 Italy

Negas (Nagas) & Ray 1925-28 Italy

Milan-based motorcycle importers established by Allesandro Negas (Nagas) and Tullio Ray, who for three seasons built unit construction 350cc side-valve models with large outside flywheels designed by Giuseppe Remondini. Introduced an ohv version in 1927. Unsure of survivors, but confusingly the company name appears on transfers of some of their imported machines, including stock Indians, Zundapps and the like which do survive today.

Negrini 1954-c1984 Italy

Vignola-based firm, who began production with 110/123cc two-stroke motorcycles then moved into quantity manufacture of 49cc mopeds, motorcycles and off-road models. Motocross and road motorcycle models occasionally find their way into the UK.

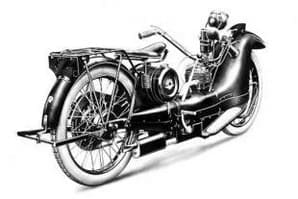

Ner-a-Car 1921-27 USA and UK

The nearest and most successful thing to a car on two-wheels. Never enjoyed racing success, but gained orders from the RAC and many arty or academic motorcyclists, including the writer Dorothy L Sayer. Whether they were attracted to the rider protecting extensive front bodywork, hub centre steering, low centre of gravity or even the novel gearing on the two-stroke models, is anyone’s guess. But what is certain is briefly this Odd-Man-Out profitably bucked the trend, ensuring a healthy survival rate for those who fancy something different.

American designer Carl A Neracher of Syracuse, New York filed patents in 1919 for ‘his’ motorcycle. It took him another two years to assemble a finance package, including cash from safety razor magnate King C Gilette, before production of 211cc two-stroke motorcycles began at 196 South Geddes Street, Syracuse.

The engine was mounted with its crankshaft in line with the frame, magneto towards the back with a bronze surface to its rearward face. A transverse splined shaft carried an aluminium wheel with friction material on its outer circumference traversing the flat rear face of the magneto/flywheel. The other end of the transverse shaft carried the final drive sprocket, transmitting drive via chain to the rear wheel. Moving the aluminium pick up wheel towards the centre of the magneto flywheel lowered the gearing and vice versa.

Left hand twistgrip mechanism pressed or lifted the aluminium wheel from the magneto, acting as a clutch. In theory the system gives infinitely variable gearing but many friction drive Ner-a-Cars have a notched gate limiting the operational lever movement to five gear options.

Left hand twistgrip mechanism pressed or lifted the aluminium wheel from the magneto, acting as a clutch. In theory the system gives infinitely variable gearing but many friction drive Ner-a-Cars have a notched gate limiting the operational lever movement to five gear options.

Ner-a-Car production started at the Syracuse factory c1921 with their own 211cc two-stroke engine for the American market. Looking to increase sales, Ner-a-Car began exporting models to the UK via the Intercontinental Engine Company, Victoria, London, but not before a second brake had been fitted to the rear wheel to comply with British legislation, requiring two independently operating brakes. To fit a front wheel brake would have been difficult due to the hub centre steering and US law required only one brake.

Quality car maker Sheffield Simplex of Tinsley, Sheffield, were looking for another enterprise and after much negotiation secured a licence from Carl Neracher to totally build the Ner-a-Car in the UK. Despite their Tinsley base, Sheffield Simplex rented part of the Sopworth Aviation works, Canbury Park Road, Kingston-upon-Thames, which had just been vacated with the end of ABC production.

Sheffield Simplex revised the engine design to give a 285cc unit with roller instead of taper main bearing, a single electric headlight in place of the US model’s double lights and some other minor changes. Drawing on Sheffield Simplex expertise marketing quality cars to the ‘better off’, Ner-a-Cars found a lucrative ready market amongst the upper classes – clergy, doctors, lady riders and artists as well as motorcyclists who wanted a more stable machine with superb weather protection.

Although the two-stroke engine was listed throughout the marque’s UK production run, four-stroke 350cc side-valve Blackburne powered models with conventional three-speed gearbox were soon offered. These models usually had acetylene rather than electric lamps.

By 1924 the American operation had ended production. National concerns including the RAC, began buying Ner-a-Cars in quantity and in 1926 a 350cc ohv Blackburne engine with swing arm rear suspension was launched. All went swimmingly, until a full page advert in the motorcycle press of 14 October 1926 announced the end of production. A tragedy as even in the hard pressed times of the mid-1920s Ner-a-Cars were strong sellers and the business in profit. But it was felled by its Sheffield parent company. At Tinsely, quality cars had given way to Sheffield Simplex lorries which struggled and the motorcycle division couldn’t keep the lot going.

By 1924 the American operation had ended production. National concerns including the RAC, began buying Ner-a-Cars in quantity and in 1926 a 350cc ohv Blackburne engine with swing arm rear suspension was launched. All went swimmingly, until a full page advert in the motorcycle press of 14 October 1926 announced the end of production. A tragedy as even in the hard pressed times of the mid-1920s Ner-a-Cars were strong sellers and the business in profit. But it was felled by its Sheffield parent company. At Tinsely, quality cars had given way to Sheffield Simplex lorries which struggled and the motorcycle division couldn’t keep the lot going.

As with most vintage machines, parts supply is difficult although 350 sv/ohv Blackburne engines turn up at selected autojumbles. But if you want to stand out from the vintage crowd with something different that works you could do worse than a Ner-a-Car. 285cc two-stroke single or 348cc sv single, variable gear (five-speed) or three-speed.

Note: The Ner-a-Car was built in the same factory but in a different part as the Sopworth-backed Harry Hawker built Hawker.

Nestoria 1923-31 Germany

Production started at this Nuremberg factory using Nestoria’s own 289cc and 346cc single-cylinder two-stroke engines. After taking over the Astoria marque in 1925, Nestoria fitted predominately Kuchen engines but also Swiss MAG and British Sturmey-Archer units. Often machines were tailored to customers’ specifications.

New Comet 1905-32 UK

Birmingham engineering firm whose owner designed and built motorcycles using proprietary engines including Peco, Villiers, JAP and Precision. Falling sales saw production end c1924 but briefly restart in 1931 using 196cc Villiers units. New Comet is one of at least 16 marques whose brand began with ‘New’ – all had ended manufacture by WWII. (However, New Hudson resurfaced during the war and again after WWII when BSA took over production from the original New Hudson company.)

New Comet enjoyed brief moderate success both in the IoM and at Brooklands, including class E (lightweight sidecar) records for Frank Newey’s 293cc New Comet-Climax and a fifth for LW Clements in class B (up to 350cc), again with a 293cc New Comet-Climax. A small number of early 1920s 269cc Villiers-engined lightweights survive.

New Coulson 1923-24 UK (Coulson and Coulson B 1919-24 UK)

New Coulson 1923-24 UK (Coulson and Coulson B 1919-24 UK)

Assembly of the Coulson range, some of which had a spring frame designed by F Aslett Coulson, began at King’s Cross, London, using proprietary engines including side-valve and ohv JAP and Blackburne engines. Later the business was bought by AW Wall and then HR Backhouse & Co Ltd, who moved production to Birmingham, by which time 346cc ohv oil-cooled Bradshaw engines were being used and the model had become the New Coulson after previously being renamed the Coulson B.

The marque enjoyed brief TT success with a best result of fourth in the 1922 Junior for R Lucas (348cc Coulson) and a number of Brooklands wins, including the 1921 Junior Brooklands TT Race for Eric Longden at a race speed of 54.67mph astride a 348cc ohv V-twin Coulson-JAP.

New Gerrard 1922-40 UK

The first we southerners knew of Jock Porter and his New Gerrard was in 1922 as Porter’s Motor Mart of Edinburgh entered Jock for the Junior TT race on a 348cc model. Already an established rider at Scottish speed events, Porter was disappointed to retire on lap two but he came good the following year winning the Lightweight TT at 51.93mph and then the 1924 Ultra Lightweight TT at 51.20mph, setting fastest lap, also aboard a Blackburne-engined machine of his own design.

Although he continued to support the TT until 1931, he recorded a long list of retirements, with third in the 1925 ULWand eighth in the 1928 LW races, his only other places. Through the 1920s Porter regularly travelled to Continental meetings, winning the 250cc class of the Belgian GP in 1925, 1926 and 1929 and finishing second in the 1928 French GP and the GP d’Europe.

Although he continued to support the TT until 1931, he recorded a long list of retirements, with third in the 1925 ULWand eighth in the 1928 LW races, his only other places. Through the 1920s Porter regularly travelled to Continental meetings, winning the 250cc class of the Belgian GP in 1925, 1926 and 1929 and finishing second in the 1928 French GP and the GP d’Europe.

Without doubt motorcycle racing was the major influence that helped encourage Jock to build his own brand of excellent handling, often sporting motorcycles. He capitalised on his racing success to publicise his products, which began with Blackburne and Barr & Stroud power, then Blackburne alone and finally JAP, which continued after Blackburne engine manufacture ended. Initially machines were built in Edinburgh by Porter, then, as trade increased, much work was farmed out to the Campion factory at Nottingham. After Campion closed, Jock continued building his motorcycle, often buying ready-made frames. Although production was scaled down after Jock retired from racing in 1931, the New Gerrard was built in small numbers until 1940.

New Henley (Henley) 1920-29 UK

Birmingham-based maker founded as Henley by the Clarke brothers, who traded for some years from Steward Works, Doe Street, Birmingham, with finance from their father. Began production using 269cc Villiers two-stroke engines then added to their range, fitting side-valve and ohv Blackburne and JAP single-cylinder and V-twin engines plus ioe MAG units. Other engine options were available and machines were built to customer specification. Often struggling financially, the firm was restructured at regular intervals with cash injections from an increasingly reluctant Mr Clarke Snr.

Finally in 1927 the Clarke brothers were forced to sell their business, when their father ended support, to racers Arthur Greenwood and Jack Crump, who transferred production to Oldham. Unfortunately, timing was poor with the UK heading for recession; sales failed to pick up, leading to the firm’s closure in 1929. It was a shame as the Henley/New Henley were attractive and, at times, sporting motorcycles. However, a modest number survive.

New Hudson 1903-04, 1910-33, 1940-58 UK

New Hudson 1903-04, 1910-33, 1940-58 UK

Well-known Birmingham cycle-makers Hudson and Edmunds enjoyed a healthy growth in sales during the late Victorian period when also the Armstrong cycle hub gear was gaining popularity. Joining forces under a financial restructuring agreement, the two businesses became the New Hudson Cycle Company Ltd. The company expanded to running three factories at Icknield Street, Parade Street and Summer Street, Birmingham.

Keen to expand their business, New Hudson experimented with motorcycles, fitting either Belgian-built Minerva kits to their own cycle frames or motorising heavyweight cycles with De Dion or De Dion-like engines. They must have been only lukewarm about the project as little more was heard until 1910, when the company simultaneously launched the Armstrong three-speed hub with an all-metal multiplate for motorcycles and two complete machines with either 292cc or 500cc side-valve JAP engines. The larger-engined model was no more than a stopgap as, in 1911, New Hudson unveiled their own 499cc engine with rear-mounted magneto driven by inverted tooth (silent) chain.

Although factory TT entries secured a best of 13th in the Junior, New Hudsons were being used around the world gaining top results, especially in long distance events. For the 1913 season the 292cc JAP was replaced with a 346cc single and a 770cc V-twin was unveiled. The following year came a small 367cc V-twin and a durable 211cc two-stroke, New Hudson making the engine under licence from Levis. Despite offering their 499cc single as the Service Four, the factory was turned over to munitions work as their effort for WWI, although they continued to list a limited range of civilian motorcycles based predominately on the 211cc two-stroke and 499cc side-valve single for the next two years.

Postwar production restarted with the two-stroke model, which continued until 1923 with small-capacity increases. These included the 247cc, which was fitted to racing models including the 1921-2 Lightweight TT entries. Four-stroke motorcycles soon followed the restart of the two-stroke lightweights, first with an update of the pre-WWI 499cc model, then a 594cc side-valve single, a 346cc side-valve single and a redesign of the 499cc model to give a 496cc single. A larger 550cc model followed, as did ohv engines starting with the 346cc version soon joined by larger models in readiness for the 1924 TT.

Despite all this, the TT models were ill-prepared, with all four Junior and Senior entries retiring. Fortunately, sales remained steady, so the management approved another winter of racing development that led to fully-pumped, dry sump lubrication and alloy connecting rods. Then the bosses pulled their ace card, tempting famed Brooklands racer Bert Le Vack from JAP (who officially withdrew from racing) to head the New Hudson race programme at the start of 1926.

Despite all this, the TT models were ill-prepared, with all four Junior and Senior entries retiring. Fortunately, sales remained steady, so the management approved another winter of racing development that led to fully-pumped, dry sump lubrication and alloy connecting rods. Then the bosses pulled their ace card, tempting famed Brooklands racer Bert Le Vack from JAP (who officially withdrew from racing) to head the New Hudson race programme at the start of 1926.

With development, Le Vack was soon lapping the 496cc single at Brooklands at over 100mph and later established a number of class records. A works three-man team went to the IoM with Jimmie Guthrie second in the 1927 Senior, Oliver Langton seventh and Tommy Bullus retiring on lap two. All Junior entries retired. Le Vack set new Brooklands flying start five-kilometre and five-mile records at 105.49mph and 105.42mph respectively, and took the year’s 600cc sidecar 200-miler at 68.9mph with an overbored 496cc model.

With these and many other speed results the future looked good for New Hudson but Le Vack’s contract expired and the New Hudson management didn’t have the foresight to renew it. Despite having built some cracking roadsters, by 1929 New Hudson slipped behind the game, with sales dropping dramatically. Vic Mole was tempted from Ariel as general manager and, with motorcycle production centred at the St George’s Works, Icknield Street, Birmingham, it was a case of out with the old and in with the new. From the drawing board of Arthur Woodman came a full range of smart, semi-enclosed, side-valve and ohv singles headed by the top-of-the-range tuned Bronze Wing. Unveiled at the 1930 Olympia Show, they were much admired but again sales were slower than the board wanted.

Unfortunately, despite a few mechanical teething problems and reservations about the engine enclosure, the product was reasonable but the timing wasn’t. The UK, like much of the world, was fighting its way out of the worst depression ever known. The board continued to support the motorcycle division for a couple of years but in 1933 pulled the plug and the St Georges Works closed.

New Hudson re-entered the powered two-wheel game in March 1940 with the rigid-framed clutched single-speed 98cc Villiers Junior De Luxe-engined autocycle built at the Garrison Lane factory. Aimed at the essential user and wartime working person, the New Hudson was a successful concept leading BSA to acquire the marque and restart autocycle production after the war. This was initially with the JDL engine, which was replaced in 1948 with the upright cylinder 99cc Villiers 2F clutched single-speed unit.

The autocycle proved a nice little earner for BSA until the invasion of 49cc Continental mopeds took hold, cutting into autocycle sales. By 1956 many makers had dropped the 99cc single-speeders but BSA had one more go at redesigning the machine’s bodywork to give us the so called ‘Restyled’ New Hudson. Although it was selling moderately well, BSA could see the moped would win the day, dropped autocycle production and ended New Hudson’s final fling. However, it wasn’t the end of the original New Hudson company as they continued with manufacture of suspension units, brake parts etc using the brand name Girling, after selling the New Hudson brand-name to BSA.

The autocycle proved a nice little earner for BSA until the invasion of 49cc Continental mopeds took hold, cutting into autocycle sales. By 1956 many makers had dropped the 99cc single-speeders but BSA had one more go at redesigning the machine’s bodywork to give us the so called ‘Restyled’ New Hudson. Although it was selling moderately well, BSA could see the moped would win the day, dropped autocycle production and ended New Hudson’s final fling. However, it wasn’t the end of the original New Hudson company as they continued with manufacture of suspension units, brake parts etc using the brand name Girling, after selling the New Hudson brand-name to BSA.

Since New Hudson built the majority of their own motorcycle engines, spares can be a problem, but the effort is worthwhile as most perform well and many of the side-valve models have a sporting nature. The Villiers autocycle engines enjoy good spares reliability and proved durable in service.

New Imperia 1947-58 France

Villefranche-sur-Soane works that assembled lightweights, often with AMC engines. Also built a duralumin-framed model. ![]()

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.