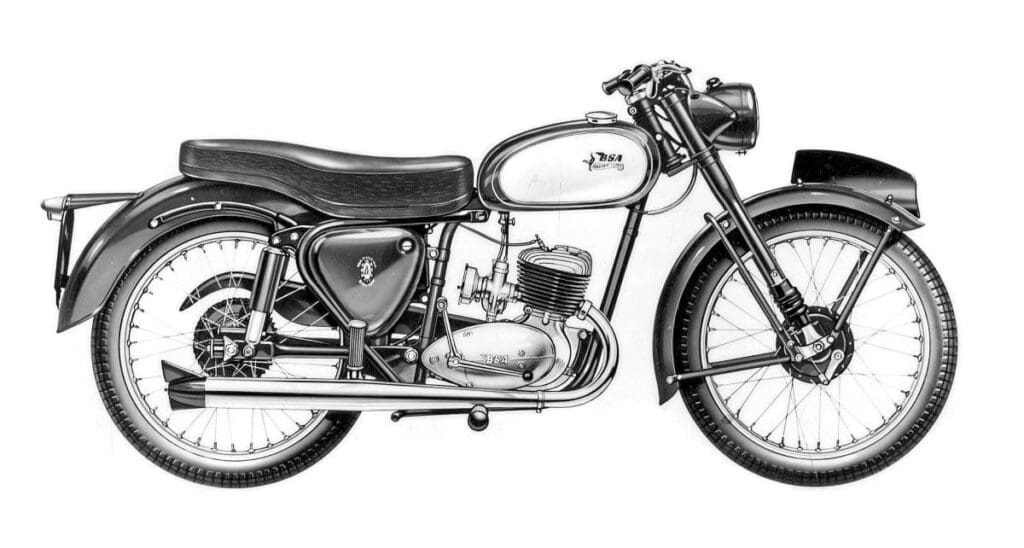

Small, simple, and easily dismissed – until you ride one. Why BSA’s unassuming D1 Bantam deserves more respect than it gets.

Words: Phil Turner Photographs: Gary Chapman

It’s easy to overlook a Bantam, particularly when one is parked in a line-up of larger, more glamorous machines at a show; or like this one, sharing page space with the immaculately restored and the rare.

Though many will have moved up the capacity ladder as soon as experience and wallet allowed, most motorcyclists of a certain vintage will have started their two-wheeled career on a Bantam. The rest will have ridden to work on one, or if they didn’t a member of their family did.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

How do we know this? Well, park any model in any UK town and it’s only a matter of minutes before someone will come over and spark up a conversation about it: ‘Ah, BSA Bantam. I used to have one of them’ is how it usually goes. The opening gambit usually followed by a brief outline of what they went on to ride next, and then how the partner and family came along and two wheels had to be replaced by four.

It’s not surprising that so many have memories of the humble BSA. Depending on where you get the number from, between 250,000 and 500,000 of them made their way off the BSA lines over its 23-year lifespan, into most facets of motorcycling. People went to work and back on them, some delivered telegrams on them. Others competed on them – on Tarmac and trails. People have even travelled the world on them; notably Gordon May, who rode a 1952 D1 called Peggy, from the UK to Egypt and back – a book well worth reading if you haven’t already.

I’ve ridden a handful in my time: a D7, a B175 in full Post Office trim, and a D14 Sports – and though only for road-testing purposes, every time I’ve ended up wanting to ride each one off up the road and take it home. I’d never ridden a D1 though…

A Bantam for every rider

For those unfamiliar with the tale, the Bantam’s origins lie not in Small Heath but prewar Germany, with DKW’s RT125. Like so many German industrial designs, it became Allied war reparations after 1945, distributed freely among the victorious nations. The design proved irresistible – Harley-Davidson, Yamaha, WSK in Poland, Russia’s Voskhod, and MZ (who’d inherited the original DKW factory) all produced their interpretations.

BSA’s approach was characteristically different. Rather than simply tweaking the design and sticking a BSA badge on it, they reversed the entire engine layout, creating a mirror image of the RT125. This moved the gear change and kick-start to the right-hand side – a configuration more familiar to British riders – converted fittings to imperial measurements and incorporated British electrics. It was an elegant solution that made the design thoroughly British while retaining its proven fundamentals.

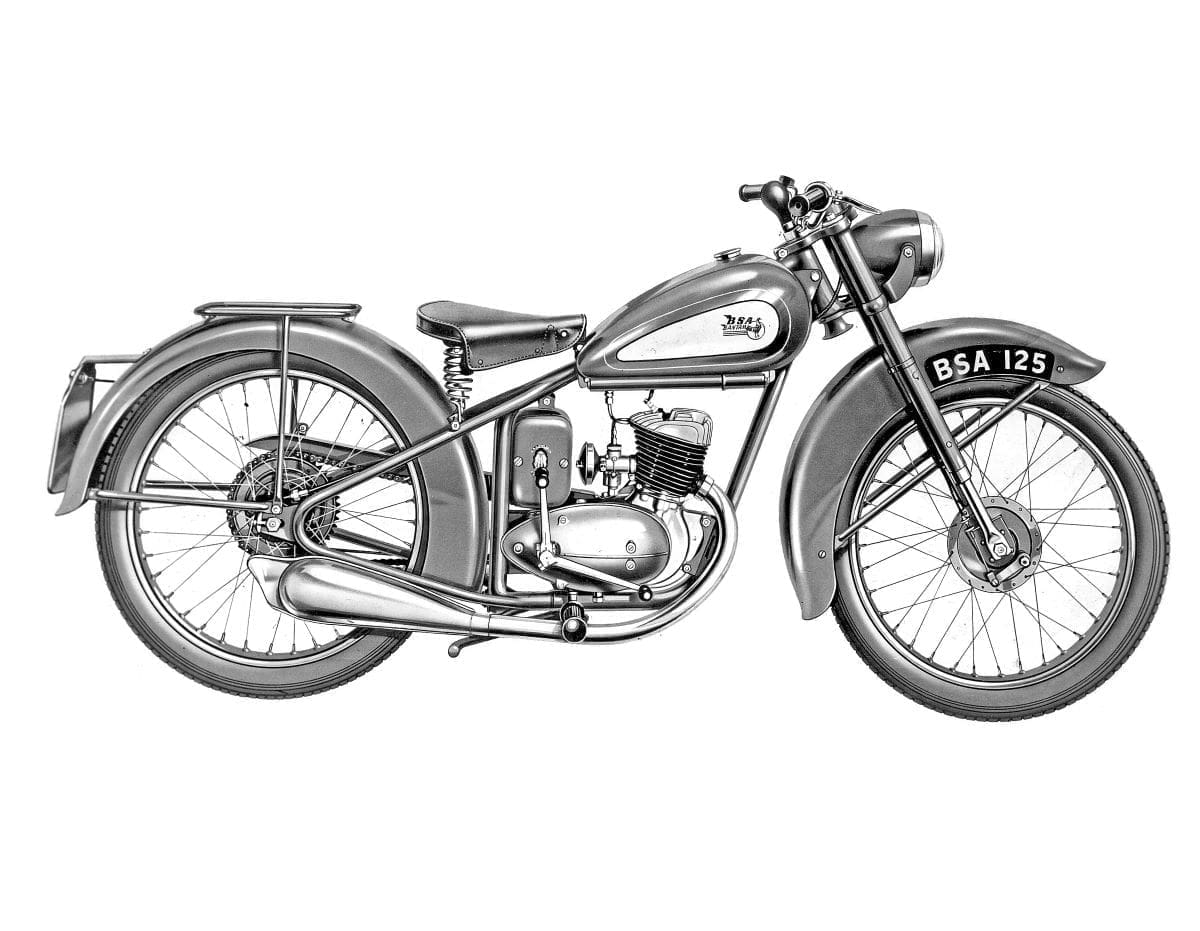

Initially produced as engine-only units for export, complete machines appeared by late 1948, designated the ‘D1 Bantam’. The 123cc displacement came from that characteristic 58mm stroke shared by all Bantams, paired with a 52mm bore. Unit construction housed the two-stroke single and three-speed gearbox; thoroughly modern for its day.

The early D1 was simplicity itself: rigid frame and a basic chassis, and electrics. This single specification ran through to 1955, though by 1950 BSA had begun expanding the range and the D1 became available with rigid or plunger suspension, Lucas or Wipac electrics. There was also a competition variant offering an even broader choice: rigid or plunger frames with Lucas, Wipac, dry cell, or magneto-only ignition. D1s were made from 1948 to 1963 the longest production run of any model and at its peak, eight different specifications were available.

For the hard-pressed working men and women of late-1940s Britain, the humble BSA Bantam D1 was perfect: cheap, lightweight, economical and simple. For those of the 1950s, it wasn’t quite enough: by then the scars left by the Second World War were healing, increasing production saw export earnings and investment rise, and millions of Britons were now in work and earning more. Our standard of living was on the up, consumerism was starting to take hold; we wanted it, we felt we’d earned it and we could now afford it. The Bantam had to keep pace, and so followed 150 and 175cc capacity hikes, swinging arm suspension, and myriad models – like the Tiger Cub, there was a Bantam for every rider (see sidebar), but that’s a different story…

You’d be mad to touch it

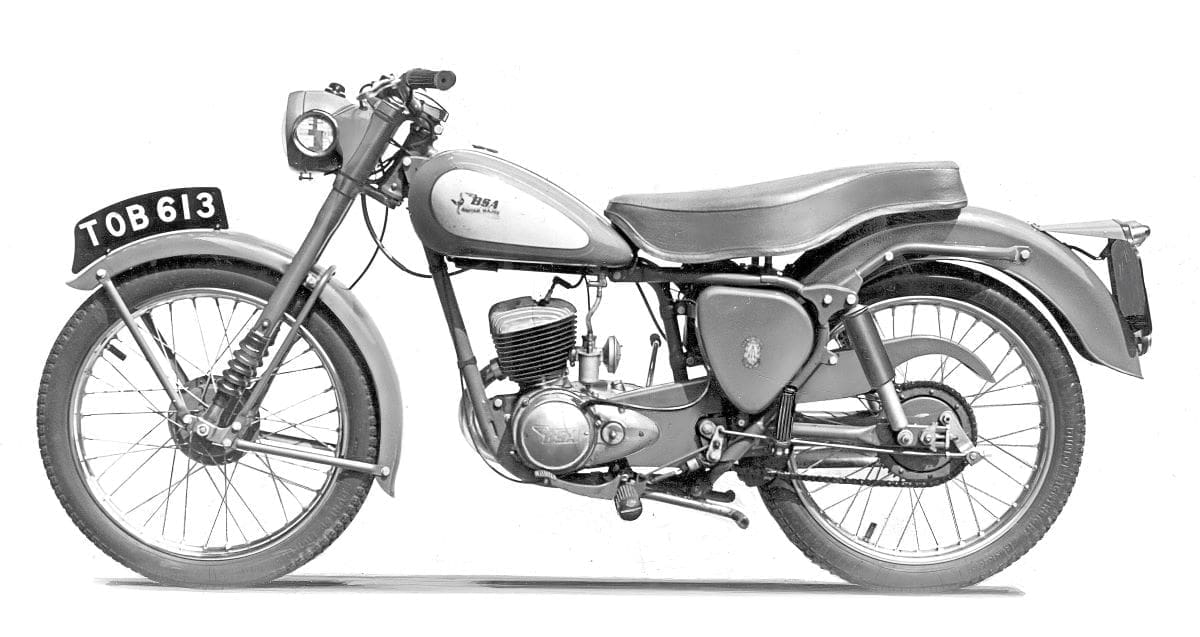

The story of this particular D1 – a 1953 model – is a simple one, so I was told. Registered new in Norfolk, it had stayed in the county and under the custody of one owner, until it made the journey across the border to Suffolk and into the inventory of dealer Andy Tiernan (www.andybuysbikes.co.uk) earlier this year; the owner, BSA enthusiast, thinning out his collection.

I’ll be honest, though it was positioned front and centre outside the workshop, amongst the ‘recently arrived’ machines waiting for the once-over by Andy’s mechanic Pete, I hadn’t noticed it at all; its size and that austerity Mist Green paint overshadowed and quite literally outshined by the larger, chrome-laden machines around it. What made it so appealing was just that: its completely honest condition.

Here was a machine wearing its history proudly – mismatched paint on panels where it had obviously been touched up over the years, a light patina of surface rust, scrapes and knocks picked up along the way, and a small bullet tail-light that had clearly been added at some point. It was about as authentic as you could get, with that all-important ‘lived-in’ look that tells the story of decades of faithful service that many try to replicate. When the inevitable question arose – restore it or leave it as is? – editor James, Pete, Andy and I were unanimous: you’d be mad to touch it.

“Is the D1 rideable?” I asked.

“I haven’t had a chance to have a look at it yet,” Pete replied, “Give me five minutes.” Sure enough, it wasn’t long before he wheeled the little D1 back out of the workshop and buzzed off up the yard to make sure all was functioning well.

Uncomplicated

The first thing that strikes you about a Bantam is just how small and light they are; almost bicycle-like in dimension and weight. It makes them incredibly easy to handle, both in and out of the shed. Starting is equally straightforward, even from warm; this example fired up on the second kick with just a tickle of the tiny carburettor. There’s a simple strangler mechanism for colder mornings, but nothing more complicated than that.

There’s absolutely nothing intimidating about a Bantam – any Bantam, really – but the D1 in particular is just an easy thing to get along with. Although this example was clearly showing it had lived a full life, nothing needed a second thought to operate. The clutch was light, the gearbox positive, the brakes adequate and working fine, and the little 123cc unit providing just enough performance to keep pace with modern town traffic and potter along smaller country lanes without any drama whatsoever.

Get it onto a larger road or into busy traffic, however, and the little BSA quickly starts to feel out of its depth – the 150 and 175cc models are a much better bet if you’re planning to tackle modern traffic regularly. And ‘little’ is very much the operative word here: sandwiched between the increasingly mammoth modern cars that seem to grow larger by the year, you quickly feel vulnerable and invisible on something as diminutive as the D1. But don’t expect too much from it and the Bantam becomes a thoroughly relaxing experience. What strikes you most is how uncomplicated it all is. You don’t think about riding it; you just get on and ride. There’s something almost therapeutic, in fact, about its modest capabilities and gentle nature. It encourages you to slow down, take the back roads, and rediscover the simple pleasure of just being on two wheels without any pretensions or complications.

Unassuming

It’s precisely these attributes – reliability, simplicity, economy, and that complete lack of intimidation – that made Bantams so numerous and ubiquitous in their heyday. They became workhorses relied upon worldwide because they simply got on with the job without fuss or drama. Postmen, commuters, learners, and anyone who needed dependable, economical transport could climb aboard and trust the little BSA to deliver. Today, those same qualities make the Bantam an ideal first classic or perfect back-lane companion. Rugged and reliable – if looked after, of course – and still reasonably cheap to buy, run, and maintain, there’s little to go wrong and much to enjoy.

Which brings us back to where we started: while it’s easy to overlook a Bantam when more glamorous machines are vying for attention, you’d be daft to do so. Sometimes the most unassuming motorcycles prove to be the most rewarding.

Fancy a Bantam? There’s plenty to choose from.

D1 (1948-1963)

The original 123cc. Started rigid-only, gained plunger rear suspension option in 1950. Various electrical systems available; Wipac AC/DC or Lucas. Dual seat option from 1953. Maroon finish available from 1958 alongside mist green. GPO versions continued to 1965.

D3 Major (1954-1958)

First evolution – bore increased to 58mm for 148cc and 5.3bhp. Enlarged cooling fins, swinging arm suspension from 1956. Finished in pastel grey with ivory tank panels.

D5 Super (1958 only)

Brief 173cc variant with 7.5bhp. Amal Monobloc carb, two-gallon tank, maroon with ivory panels. One year only – clearly BSA had other ideas brewing.

D7 Super (1959-1966)

The glamour model. 173cc engine with alloy outer cover, hydraulically damped forks borrowed from the Tiger Cub, headlamp nacelle. Chrome tank panels and pear-drop badges from 1961. Economy ‘Silver Bantam’ in final year.

D10 (1967 only)

Power boost to 10bhp with higher compression. Four variants: Sports and Bushman with four-speed boxes, Supreme and Silver with three-speed. Sports got chrome guards and flyscreen, Bushman went off-road with high exhaust and 19-inch wheels.

D14/4 (1968)

Higher compression again for 12.6bhp, four-speed standard across the range. Heavier forks on Sports/Bushman models. Some reliability issues with flywheel rivets and small-end bearings.

D175/B175 (1969-1971)

The final fling and arguably the best. Revised engine with central spark plug, improved combustion chamber. Triumph T20 forks, stronger kick-start. Finished in metallic red/blue or black with white lining.

Bushman variants

Off-road versions available from D7 onwards, mainly for export. High exhaust, sump guard, raised engine mounts. 300 UK examples of the final B175 Bushman – now highly sought after.