Sometimes, it’s nice to be pleasantly surprised, as the experience with this Royal Enfield Constellation proves.

Words: James Robinson Photographs: Gary Chapman

Prior to one of our regular journeys to Andy Tiernan’s motorcycle emporium in Framlingham, Suffolk, we’d spoken to Andy and agreed a list of motorcycles that he would have available, including some from his private collection at home.

Amongst the others we had discussed was a lovely charcoal grey Triumph Thunderbird, but that was sold and collected the day before our visit – such is the situation when arranging to borrow dealer machines. But we, (writer Phil Turner and photographer Gary Chapman) and I still had a full roster to go at, ranging from tiny two-strokes to big capacity four-strokes, and covering about 40 years.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle Magazine reading every month.

Click here to subscribe & save.

There was one machine, though, which had been on Andy’s stock lists for a while, and which we included almost as an afterthought, to do ‘if we had time’. It being a 1963 Royal Enfield Constellation, all 693cc of it – which for a brief time (after Square Four production ended in 1959) made it the biggest production motorcycle on sale in the UK. Indeed, this actual machine even features in this year’s ‘Tiernan calendar’, sold in aid of Air Ambulance, where it is superbly illustrated by Mike Harbar.

As I’d never ridden a big Enfield twin, and with the Thunderbird gone, I requested that we do something with the Constellation, to which Andy readily agreed, with mechanic Peter detailed to give it a dose of looking-at and the once-over earlier in the week before we arrived.

One can’t pretend that it was the highlight of the anticipated outing. You’ll see in due course some of the other things we rode that day, but, let’s say, the Enfield was not the biggest pre-event excitement. At Andy’s, we took it outside and while Phil and photographer Gary, were ‘doing’ another bike, Peter handed me a fuel can, and so I sloshed some go-juice in, and then, after turning on the ignition, gave it a good old kick, and it burst into life. Sounded keen, too, and so my enthusiasm was a little piqued.

Leaving the others to get on, I settled in the saddle, feeling right at home immediately, then turned right out of Andy’s gateway and set off into the Suffolk countryside.

Sometimes, one clicks immediately with a motorcycle and with others, one never does. To my surprise, the Enfield was in the former camp, far more than anything else I rode that day. And far more than some things I’ve owned, too. It straightaway felt right, I loved that I felt ‘in’ it rather than on it, which is perhaps due to the much-sat-upon seat having lost some of its supportive padding, but that meant it just felt like my old settee, comfy and familiar.

Similar to my settee, the aged Enfield looks a bit like it’s seen better days, too, but looking down from the saddle, despite being able to see the unfortunate ding to the petrol tank, I liked the way the once-bright metallic red paint had faded, mellowed and became a bit weather-beaten, while the sweep of the handlebars just suited my wrists nicely.

I settled into the traffic, gradually catching up a lad on one of those noisy 125cc four-stroke race reps seemingly beloved of today’s youth, while he in turn was catching up the cars ahead of him. The droning noise of the Yamaha in front (for that’s what it was) quickly became tedious, and on a twisty road, in a line of traffic, chances of overtakes were slim, so I took a turn down a random backroad and settled into a different pace, making a mental note to remember which way I’d come and to not go too far, as I’d not put that much petrol in.

But now at a slower pace of life, the Enfield felt lovely too, just pottering about but with an eagerness to accelerate at pace too, slightly impatient to get a move on, but uncomplaining. As I was now in danger of getting lost, I deemed it prudent to head back the way I came, before the petrol was all gone and a search and rescue party had to be deployed. But I’d have happily spent the afternoon just riding the Enfield.

Back at Andy’s, Gary and Phil had finished what they were doing and were watching the empty road, as time ticked on and I’d vanished – sorry boys. But we were soon back on track and the Enfield was back and forth for the camera, just as at home doing feet up turn in the roads, as it had been in 60mph traffic. What a nice bike it is.

Really, it’s to my detriment that I was surprised, for Royal Enfield was a company which knew how to build a good motorcycle, a reputation it continues to enjoy to this day, too. It also builds twin-cylinder models again now, after years of a ‘singles only’ policy, following the 2018 launch of its parallel-twin Interceptor 650 and then Continental GT 650 in 2019. Though as yet the Constellation name hasn’t been reused, there is a Super Meteor 650, as well as Classic 650, Shotgun 650 and Bear 650, all based around the same air-cooled four-valve engine.

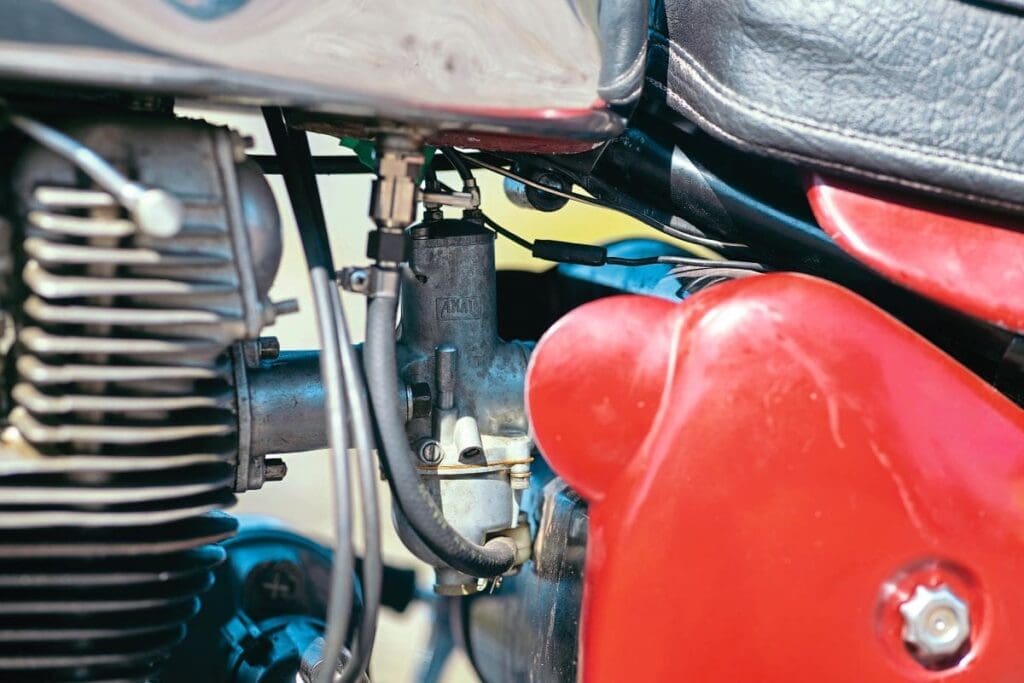

The original Constellation was launched for 1958, in its first-year incarnation featuring a decidedly racy Amal TT carburettor. This was perhaps to distinguish it from the (original) Super Meteor it appeared alongside, which was possessed of the same 693cc twin-cylinder engine, that itself having come out of, and replacing, the Meteor, launched in 1953, and based upon the unimaginatively named ‘500 Twin.’ Meteor was a much better moniker, and sat alongside the Bullet more happily than the informative-but-uninteresting ‘500 Twin’ effort.

The 500 Twin had been Royal Enfield’s first parallel twin, joining all the other makers in the rush to market for what was the ‘must have’ model in pretty much every makers’ post-Second World War range, at least those with intensions of being ‘mainstream.’ But Royal Enfield had made lots of twins in the past, though these were of the V-twin configuration, a layout that had history with Royal Enfield to before the First World War. This even brought the company sporting success, with a best of third place in the 1914 Junior TT, courtesy of Irishman F J (Fred) Walker – a success with a tragic ending, for having crossed the finish line to claim a podium place, a barrier had been put across the road and poor Walker – perhaps dazed after an earlier crash – hit it and died as a result of his injuries. His machine (XOT 4) survives in the National Motor Museum at Beaulieu and I’ve had the pleasure of riding it in the Sunbeam Club’s Pioneer Run, many years ago.

Royal Enfield has never enjoyed an Isle of Man victory, with bests being Cecil Barrow’s second in the 1928 Lightweight 250cc TT, and Steve Linsdell’s remarkable second in the Manx GP Newcomers’ race of 1981, on a 500cc Seeley-framed Bullet, in among the multi cylinder two-stroke TZ Yamahas and RG500 Suzukis. Linsdell also memorably raced a ‘big twin’ Enfield in VMCC events in the 1980s and 90s, showing many a Triumph, BSA, Norton and Vincent the way home.

There was a spell in the late 1950s when Royal Enfield went after production racing success, in an effort masterminded by Syd Lawton and famously employing racer Bob McIntyre in a riding capacity, to underline the sporting prowess of models like the Super Meteor and the Constellation, but it was the big V-twins that could often be found hauling a huge, hefty sidecar, for which the company was best known.

As mentioned earlier, Royal Enfield was in the business of V-twins early on, having first exhibited a so-engined machine in November 1909, using a 297cc Swiss Motosacoche power unit. These were soon joined by a larger (350cc) version, then in 1912 came the 771cc JAP V-twin model, the 180 – Royal Enfield’s first big twin had been born. The Model 180 was to be a mainstay of the Enfield range for many years, it gaining a 980cc JAP engine in 1915, and then from 1921 it was powered by the Vickers-built, Royal Enfield designed V-twin of 976cc, before manufacture was brought in house for 1925. The Model 180 was last listed in 1928, then came the Model K, still of 976cc.

Things became bigger too, when the gargantuan 1140cc version of the K was launched for export only in 1933, then it was joined by the KX in 1937, which became (and remains) something of a cult machine, the ultimate ‘big Enfield.’

This particular example of the later big Enfield was registered new on September 3, 1963, bearing an ‘A’ registration, the first year that letters were added after the numbers – the full registration on the machine being ADC 986A, while the DC signifies it was originally in Middlesborough. Not all councils used a letter at the end of the number until it became compulsory in 1965, by which time the letter was on to C.

In the early days, the letter ran from January 1, but the impracticalities of a rush on new vehicles (everyone buying something wanted a ‘new year letter’ so the neighbours knew they ‘doing alright…’) on New Year’s Day, meant it switched to August 1 from 1967, meaning an E only ran January 1 to July 31, 1967. This Enfield, then, was registered towards the end of the year, its new owner not wanting to hold out a few months so everyone knew he’d a new vehicle – which perhaps sums up a Royal Enfield buyer at the time, as in, not too bothered about what others thought, seeing as the big RE was overshadowed, certainly in terms of glamour, by the likes of Triumph’s Bonneville and BSA’s new A65, while in glamour and capacity by Norton’s 745cc Atlas, which had knocked the Enfield off its perch as Britain’s biggest production model.

That the feature machine before us was registered in September 1963, makes it one of the last of the Constellations produced, for the model was to be dropped from the range for 1964. Consulting Roy Bacon’s book British Motorcycle of the 1960s also brings up an interesting point; the only Constellation listed for 1963 was (to quote the aforementioned book) ‘…available only as a sidecar machine, and to this end was detuned to the Meteor specification, with low compression ratio, one carburettor and coil ignition. A siamesed exhaust system was fitted as standard, twin systems being an option. To suit sidecar use, the machine had lowered gearing, reduced fork trial, stiff suspension and a steering damper.’

Closer inspection of our subject machine reveals that it does indeed have a steering damper, has coil ignition (I know, as I forgot to switch it on at one point, which resulted in getting rather hot and bothered; me that is, the bike just did nothing…) while looking at the engine number, it also has ‘SC’ stamped on it – for sidecar, one might be safe to assume? Perhaps that accounts for its altogether eager-to-please demeanour, while one wonders if in this configuration it would produce the 51bhp Royal Enfield claimed; incidentally, the new Interceptor 650 and friends make a claimed 47bhp, so the ‘old ones’ have, in theory, more giddy-up than a brand-new machine that looks similar. Whether in reality that would be so, is a moot point.

As for the old Constellation, once it was dropped, Royal Enfield already had a new model in its range, the Interceptor, which was effectively to become a one-model range by the end of the 1960s. This was extensively redesigned (now featuring a wet-sump engine and single oil pump) for 1969, to finally get away from the oil pump/feed problems and suspicions which had always dogged the big Royal Enfield twins, apparently with some justification. But I was also told that the problems only ‘really’ surfaced if the model was thrashed from start up, which is not the antics many of us undertake with our old (or otherwise, in fact) motorcycles, not these days anyway.

For what many of us use an old motorcycle for, which is pleasant jaunts in the countryside on warm summer days, this Royal Enfield Constellation would see the stars all lined up nicely, boasting good manners, pleasing performance and a comfortable riding position. As I’d truthfully come into it not really expecting much at all, it was a pleasant surprise and a good experience to have expectations exceeded.