FROM THE ARCHIVES

The famous Edward Turner-designed Ariel Square Four has created an enviable legacy, which it owes to the careful refinement of its remarkable four-cylinder engine, among other things. This particular Square Four also has the benefit of a beautiful Watsonian sidecar, and is (if you’ll excuse the pun)

a winning combination.

Words: ROY POYNTING

Photography: TERRY JOSLIN

Darwinian evolutionary principles seem to apply just as much to motorcycles as to animals, and they either have to adapt to changing circumstances or else they fade away. Look at how the Ariel Leader fizzled out – barely changed from the initial specification – after half a dozen years, while the last Gold Star shared little except its name and engine type with its antecedent from a quarter of a century earlier.

Enjoy more Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

Following that logic, it’s not surprising that the Ariel Square Four needed to be changed practically out of recognition in order to survive for almost three decades.

As is well known the Square Four started life as a concept which Edward Turner proposed to Ariel boss Jack Sangster, who immediately gave him permission to develop it into a saleable design.

The first production model – designated the 4F31 – had a capacity of merely half a litre, and was so compact it could be slotted between the widely-spaced downtubes of an existing frame intended for the fashionable ‘sloper’ engines.

With its overhead camshaft the ‘Squariel’ (as it was immediately nicknamed) was clearly intended to be an upmarket sportster, challenging machines such as the AJS Silver Hawk, and that aim was soon rammed home by the 4F/6.32 with its additional 100cc. Sales weren’t wonderful though, partly because of the dire economic situation at the time, but also because contemporary single-cylinder sportsters gave potential customers just as much performance with considerably less weight, cost and complication.

The Squariel soon found its own niche, however, because its car-like engine characteristics made it an attractive proposition for sidecar aficionados.

For once, Edward Turner didn’t insist that his original thoughts were the best – possibly because he was earning fresh plaudits transforming Val Page’s worthy but dull singles into glitzy and saleable Tigers – and by 1937 the Square Four was designated the 4G and unashamedly aimed at the sidecar brigade. Its capacity had been increased to one litre, and the valves were now operated by pushrods instead of an overhead camshaft.

Equally tellingly, the clever design of the original engine with overhung cranks neatly joined by a central gear was abandoned so that conventional crankshafts with heavier flywheels could be incorporated. To cover all bases, Ariel also made a 600cc version of the new ohv engine and temporarily produced an economy one-litre variant called the 4H. The standard 1000cc Squariel was the real success, though, and even re-emerged as the somewhat improved 4G Mk1 after the Second World War. In 1952 it was further developed into the ‘four-pipe’ 4G Mk2, and in that form it satisfied the dwindling demand for sidecar tugs until Ariel stopped four-stroke production altogether in 1959.

The featured machine – which has just joined the display at the Sammy Miller Motorcycle Museum – epitomises the end of the first era, being first registered in June 1936. It has belonged to an enthusiast for many years, and the documentation which came with it indicates that he started its restoration in 1983. According to the dates on the bills, the work proceeded fitfully, with many parts being supplied and fitted by Ariel specialist Draganfly, and some years ago the Squariel actually went through the Sammy Miller workshop to sort out problems with the ignition switch.

The ignition – fitted by Draganfly – is actually one of the least original features of the bike, although you can only tell if you happen to notice that the ignition lead comes from the toolbox instead of the magneto. In fact, the magneto body has been converted to house an electronic pick-up which fires a conventional coil inside the box, from where the sparks are sent to the appropriate cylinders via the usual car-type distributor.

The original system can be problematic, but this one certainly works well, as the bike fires up first kick when Sammy’s head honcho Bob Stanley demonstrates it to me. But easy starting has always been a feature of this model when in good condition, as you’d expect when a single kick turns four small cylinders through several firing strokes, and Ariel famously demonstrated how easily lightweight schoolboys could start it during a 1933 Maudes Trophy attempt.

Schoolboys might have trouble holding the Squariel upright though, because it is a substantial machine by the standards of the time. That was apparently the reason the previous owner had the beautifully reconditioned Watsonian sidecar fitted by its makers – still in business after all these years. The attempt to make the device more useable was seemingly not totally successful, however, and hence the combination fell into the ever-receptive arms of Sammy Miller.

When I take to the saddle I see the previous owner’s problem, as a surprising amount of muscle power is required to manage the machine. It steers true enough, so the sidecar alignment is presumably okay, but it is reluctant to turn – things could well be improved by an alteration to the fork trail.

No matter. A regular everyday rider wouldn’t be making multiple turns as I have to during the photo session, and would soon develop the technique (and muscles!) needed for cornering. Plus he’d soon get used to, and appreciate, the lively engine. Admittedly it’s not particularly quiet mechanically – mainly because of the geared primary and timing drives – but it picks up smoothly and zestfully with a lovely drone from the exhaust. Sidecar combinations died out in the 1950s because they couldn’t match the price and performance of contemporary small cars, but 20 years earlier the Squariel and sidecar only had to compete with the likes of the Austin Seven, which had significantly less horsepower and considerably more weight. The Austin kept you dry of course, but with heaters still a distant aspiration it wasn’t much more comfortable, and I can see why a buyer might have opted for the fresh air, performance and manoeuvrability of the Ariel outfit.

His passenger might have been slightly less enthusiastic since getting into the chair requires significantly more agility than entering a car, and getting out is even more difficult. There’s a tiny door, but getting your feet through it is so awkward that passengers unable to step straight onto the seat would probably choose to stay at home. It might even be advisable for those susceptible to motion sickness to do the same, as the chair’s undamped soft springing allows it to float to such an extent photographer Terry Joslin cut short his attempt to film from the passenger’s viewpoint. However, passengers in the 1930s were perhaps grateful for any form of motorised transport, and the upholstered chair is certainly classier than a bus or a bike.

And ‘classy’ is as good a word as any to describe this unarguably handsome outfit. The headlamp houses the lighting switch and ammeter as expected, but an indication that the Squariel was regarded by its makers and buyers as an alternative to a car can be seen in the provision of a tank-top instrument panel containing a speedometer, an oil pressure gauge and an inspection lamp. There’s also a space where a clock could be fitted, and the petrol cap is retained by a neat knob rather than a mundane wing nut. The generously-sized and modern-looking tank is elegantly finished in chrome and black.

There’s little plating elsewhere – other than the expected rims and exhaust – but there’s no need for undue embellishment on this already imposing machine. Both valanced mudguards are deep enough to keep most of the road muck off the rider, and the front number plate is embellished by Ariel’s elegant art-deco curve. And most of all there’s that remarkable engine. An old adage suggests the engine of the best-looking motorcycles should fit in its frame with no room to spit through, and no design fits that criterion better. The carburettor is stuck out in front of the engine where it is less likely to overheat, but there’s no room for it in the usual place anyway; and I dread to think what contortions would be required to work on the magdyno.

Perhaps that’s another reason the previous owner gave up the struggle to use this smart and remarkable machine. But at least in the Sammy Miller Motorcycle Museum it will be seen, studied and admired by multitudes of visitors.

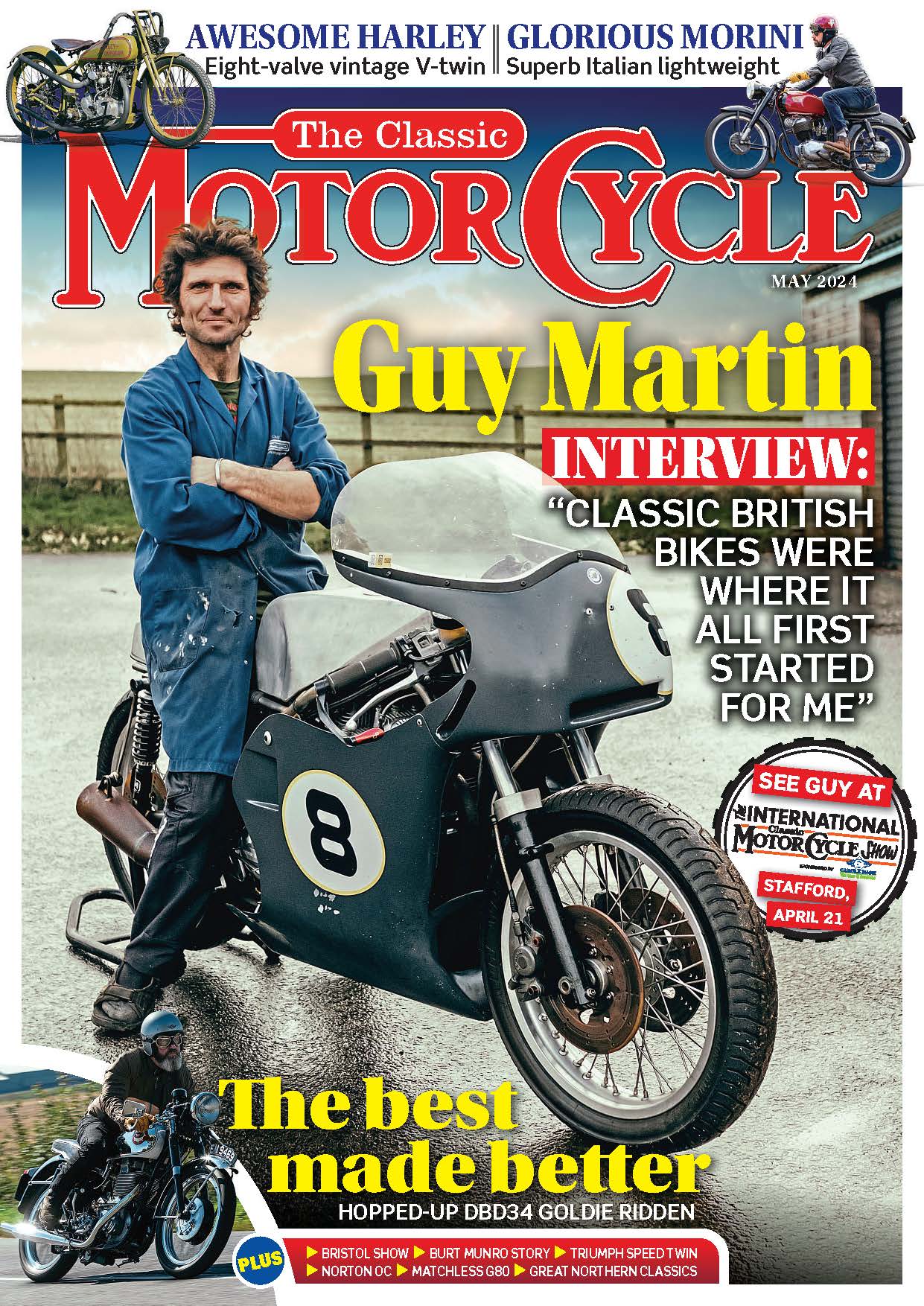

Read more Features and News in the May issue of TCM – on sale now!

Advert

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Enjoy more The Classic MotorCycle reading in the monthly magazine. Click here to subscribe.